If the character of Forrest Gump were a math wizard instead of an idiot-savant, then the name of the film would have been titled Oscar Barney Jr., as this true-life character, who lives in Evans, seemed to always find himself right in the middle of the action when history was made.

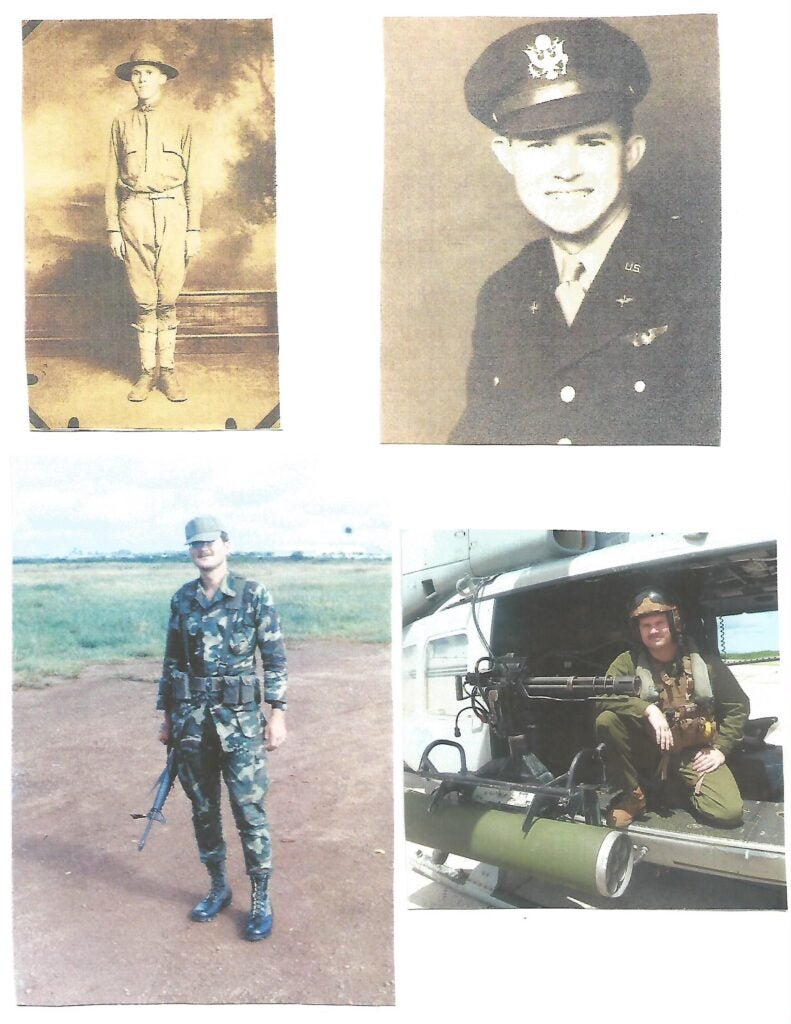

Four generations of the Barney family have served in combat under the flag of the United States and the surviving members of the family all agree that their 101-year-old patriarch is the true hero among them.

Oscar Barney, who has never liked his first name and prefers to simply be called “Mr. Barney,” is but one of four generations of one family of Americans that have served the country in wartime, and his story is so incredible that it seems to come straight out of a Stephen Spielberg script.

Barney was first interviewed by The Augusta Press in 2021; however, that original interview only scratched the surface of an incredible life spent defending the ideals of liberty and democracy.

Born in 1922 in Atlanta, Barney was raised in a military family. His father, Oscar Barney Sr., served in the army, first fighting the forces of Pancho Villa in 1915 and later serving in the European trenches of World War I.

Mr. Barney grew up with a cowboy warrior of a dad and likely inherited his dad’s sense of adventure in his genes.

“I had a good upbringing. I have to say, my parents brought me up right,” Barney said.

Prior to the onset of World War II, Barney showed an aptitude for math and attended college with that subject as a major. He also discovered a love for flying and got his single-engine pilots license when he was still but a lad of 17.

Then, a major conflict half a world away derailed Barney’s academic career, temporarily.

When World War II began, Barney first enlisted and was assigned to be an ordinance officer and a member of the Army band until the Army brass learned he could fly a plane and he was immediately sent to be trained as a navigator to fly on the storied B-17 bomber.

During training, Barney’s math skills impressed his superiors and he was also given bombardier training as well. Since digital computers did not exist at the time, both positions on the aircraft required the person to be able to accurately feed numbers into an analogue calculating machine.

Both were important jobs as one simple mistake, or errant number entered, could get the plane lost, or even worse, getting incorrect coordinates on the B-17’s Drift Meter Instrument could result in the bombing of a German hospital instead of a munitions factory.

On those planes, there was no “undo” option.

Crews who flew on the B-17 missions over Germany in World War II faced a less than 50% mortality rate on each mission. The Army Air Force lost 60 planes in one day in 1942, according to the Air and Space Forces Association.

“We knew the odds of our survival. We had fighter escorts, but when one of those big planes gets hit, the centrifugal forces cause it to spin out of control and there is no way to jump out of it,” Barney said.

The gleam in Barney’s eyes, as a centenarian recalling his airborne exploits, seems to give away his humble demeanor. Barney, as a young man, obviously loved the adrenaline rush of immediate danger and the sense of adventure that military life presented and decided to stay in the Air Force after it separated from the Army.

Barney’s son, local historian John Barney agrees and jokes that his father was full of “piss and vinegar” in his prime.

“It was dangerous, very dangerous, but I trained my mind to think of what I was seeing from the cockpit as just fireworks exploding near me,” Barney said.

Barney proved Evel Knevel a novice daredevil by flying a total of 40 missions throughout his career in both World War II and the Korean War.

On May 8, 1945, Barney was headed on a mission into the heart of what had become a defeated Germany to deal the final blows to the rump Nazi government after the suicide of dictator Adolf Hitler. Shortly after take-off, the plane was ordered to turn back as it was announced over the plane’s radio that Germany had agreed to unconditional surrender.

Barney’s plane headed towards Paris where the crew decided to buzz the big B-17 over the Eiffel Tower and they witnessed a bird’s eye view of celebrating crowds that stretched for miles.

“We flew right over the Champs-Élysées and saw the elbow-to-elbow crowds cheering. We were so low that we could see the smiles on their faces,” Barney said.

In 1948, Barney was given another mission, this time it was to help feed his former enemies as the Iron Curtain had fallen, and the Soviets had cut West Berlin off.

America responded with the Berlin Airlift.

For 18 months, planes loaded with fuel, food and water landed and took back off every 49 minutes and delivered an average of 8,893 tons of supplies per day, according to the National Air and Space Museum, in a Herculaneum effort that made America a superpower.

“Everything was timed down to the second, we didn’t waste any time either. The airlift worked without us having to fight the Russians or give up West Berlin. We fed the people, that was our mission,” Barney said.

In Korea, Barney really had his mettle tested flying over mountainous jungle terrain instead of cities where math skills were useless on guerilla fighters. According to Barney, the crew flew by the seat of their pants.

“I would see fire coming from the right and tell the pilot to veer left, but then gunfire would come from the left and we had to maneuver to avoid that, it caused that plane to bounce around like a rubber ball,” Barney said.

After his time in combat, Barney became a favored crew member when the Air Force flew dignitaries around the world to support the newly created North American Treaty Organization (NATO), and he took trips with notables such as Britain’s Lord Louis Mountbatten and his nephew Prince Phillip to peace negotiations happening in the Middle East.

After turning down a desk job at the Pentagon and a chance to help run the National American Aerospace Defense Command (NORAD) in frigid North Dakota, Barney accepted a role as Lt. Col. over the communications of the nuclear missile silos in Turkey.

Then, the Cuban Missile Crisis happened and Barney found himself and his family on the front lines yet again. Once that flashpoint cooled, Barney went into astronaut training and while he did not make it into space, he forged what became a life-long friendship with John Glenn, the first American to orbit the Earth.

John Barney says that his childhood was filled with wonder, excitement and sometimes a tinge of fear as the family traveled the globe and sometimes found themselves in unstable places.

“I remember that we were in Istanbul in 1960, and the coup occurred. We were staying just a few blocks down from the presidential palace, and we woke up to tanks coming down the road right in front of the house. We were later escorted out of the city in the middle of the night,” John Barney said.

The younger Barney followed his father into the Air Force, but found his real calling in life teaching history after serving a year-long tour of Vietnam. John Barney settled down to civilian life after the Vietnam War and retired after decades of teaching history at Lakeside High School in Evans.

“As a kid, I was right there watching it all happen,” John Barney said.

Barney’s grandson, Wesley, carried on the family’s legacy of service and recently retired after 20 years in the Marines. Wesley Barney served in Afghanistan and Iraq.

Today, Oscar Barney’s eyesight is very limited and he walks with a bit of a stoop; however, the moment he begins talking, it is clear that this American hero would willingly jump back into the cockpit today if duty called.

Scott Hudson is the Senior Investigative Reporter and Editorial Page Editor for The Augusta Press. Reach him at scott@theaugustapress.com