One of the biggest challenges facing combatants in war is the question of what to do with captured prisoners of war.

Humane treatment of prisoners of war is standard today, but in 1864, when Andersonville prison opened, the Confederacy couldn’t even feed its own soldiers. Georgia’s one war correspondent, Peter W. Alexander of the Savannah Republican had waged a newspaper campaign as early as 1862 to get supplies from citizens for soldiers in the field. Caring for Union prisoners was neither a priority nor a possibility.

The Georgia prison was established to get prisoners away from the eastern theater where they would be in easy reach of Grant’s army.

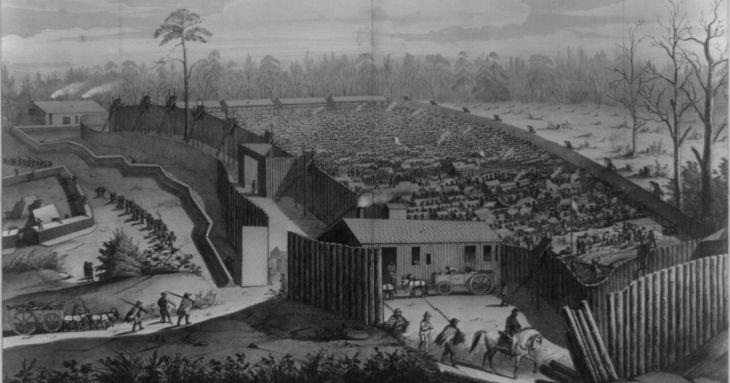

Andersonville was chosen as the site of a massive 16.5 acre open-air prison. It was rural, near the rail lines and completely forested, so there was plenty of available timber on hand.

The prison opened in February 1864 and held 45,000 prisoners at its zenith, according to the National Parks Service. Men were crammed into boxcars and moved by train to the site, named Camp Sumter.

While the area might have been perfect, the design of the prison was not so, as the Confederates placed the prison in an area that had a large creek flowing through the middle. The Confederates placed their camp upstream from the prison, meaning that urine, human and animal waste and other contaminants flowed freely into the prison.

After the war, Sergeant Samuel Corthell, Company C, 4th Massachusetts Cavalry wrote:

“The camp was covered with vermin all over. You could not sit down anywhere. You might go and pick the lice all off of you, and sit down for a half a moment and get up and you would be covered with them. In between these two hills it was very swampy, all black mud, and where the filth was emptied it was all alive; there was a regular buzz there all the time, and it was covered with large white maggots.”

The Commandant of Camp Sumter, Cap. Henry Wirz, a former Prussian soldier, was known to be ruthless beyond measure. According to the National Park Service, Wirz had a rail known as the “deadline” installed that ran 19 feet from the stockade walls.

Anyone caught crossing the deadline was shot on the spot. The soldiers up in the “pigeon roosts,” many of whom were mere boys barely old enough to shoulder a rifle, made a game of taunting prisoners with food ,and the child who murdered the most men in a day was the winner.

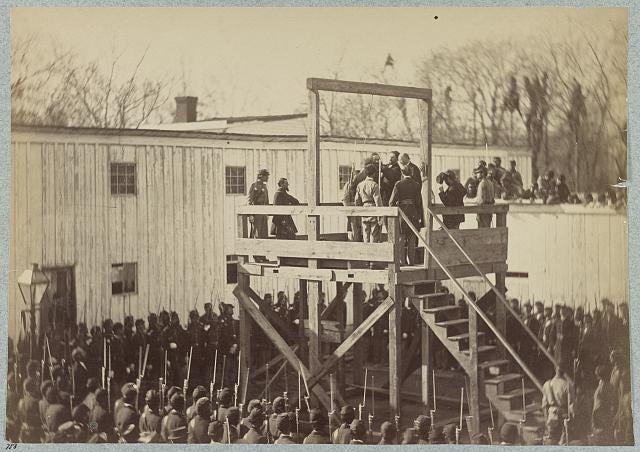

Wirz would go down in history as one of the only three Confederate officers tried by military tribunal and sentenced to death for war crimes, according to the Library of Congress.

The camp developed its own underground economy where a dry piece of hardtack, a biscuit made of flour, salt, water and sometimes sawdust, was a coveted commodity. Prisoners had to hide or bury anything valuable, such as a pocket watch.

The prisoners formed gangs and fought each other over territory within the prison.

It is estimated that 13,000, or almost a third of the prisoners died from starvation and disease.

The camp was only less than a year when Gen. William Sherman began his march through Georgia to Savannah. The Millen prison was established to relieve overcrowding at Andersonville.

For a brief two months, the 42-acre Camp Lawton in Millen became the largest prison in the world and, ironically, would be liberated by Sherman. It housed more than 10,000 men.

While the location of the Andersonville stockade was well known, the stockade at Millen was hastily abandoned, and the location forgotten until it was discovered by students at Georgia Southern University. Thousands of artifacts as well as the foundations of buildings have been found.

Well over a century after the Civil War, media mogul Ted Turner decided to shoot a mini-series about the infamous prison at Andersonville, and he wanted the film done right. Turner was quoted at the time saying, “I’m not going to let the scriptwriters tag some silly love story into a movie about war.”

Film legend John Frankenheimer signed on to direct and heeded Turner’s demands that the film be shot on native Georgia soil, when at that time, Georgia was not a favored landscape for Hollywood.

Many industry people scoffed at Turner for spending an outrageous amount of money moving the Hollywood infrastructure to rural Georgia; however, Turner would have the last laugh.

In negotiating with the state and local governments, Turner secured extremely favorable taxation status and found that he had thousands of people willing to work for non-union rates as extras.

The result is that the panoramic views shot of the prison set show thousands of prisoners milling around and not one of those extras was a cardboard cutout.

“Andersonville,” co-starring Fredrick Forrest, Williams H. Macy, Thomas F. Wilson and William Sanderson met with critical acclaim and was a financial success. Most industry-watchers agree that it was “Andersonville” that kickstarted the Hollywood migration into Georgia.

Nowadays, it is commonplace for Augustans to see the likes of Clint Eastwood and Dennis Quaid roaming around Broad Street during takes.

Meanwhile, the grounds of the real Andersonville is a serene place, a National Park Cemetery, where the bodies of the victims of the camp remain buried, a testament to the carnage and brutality of war.

…And that is something you may not have known.

Scott Hudson is the Senior Investigative Reporter and Editorial Page Editor for The Augusta Press. Reach him at scott@theaugustapress.com