Paris-based author, professor and journalist Nita Wiggins always carries Augusta with her.

“My family is always with me,” she said. “For me, when there’s a connection, it is there. Some people can be present in the same room and there’s no connection. So Augusta is my home base, because that’s where my parents are.”

Though born in Macon, Ga., the Emmy-award winning veteran sports broadcaster moved with her family to Augusta when she was two years old, first living on Hazel Street before settling in the Montclair neighborhood. Her father, Roosevelt Wiggins, had gotten work teaching soldiers at Fort Gordon’s Signal School.

“There were not so many Black families in 1973 when we moved there,” said Wiggins. “My neighborhood was becoming mixed, and we were making it mixed because it was mostly White. But because of the makeup of the neighborhood, I had all kinds of friends who were not Black people. And I find that to be my Augusta experience.”

Wiggins says Augusta was a great place to grow up, noting the safe, stable environment of the neighborhood and her nurturing home life.

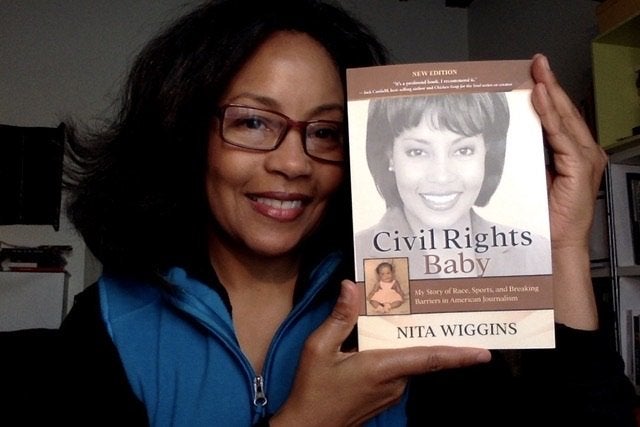

She also says in her memoir, “Civil Rights Baby: My Story of Race, Sports, and Breaking Barriers in Broadcast Journalism,” that one particular experience, what Wiggins calls the worst day of her adolescence, proved to be both a painful and powerful catalyst for who she became.

When Wiggins was a sixth-grade student at Warren Road Elementary School, a music teacher played a record of Negro spirituals in class as part of the weekly lesson. She urged 12-year-old Wiggins, one of two Black children attending the school at the time, to sing the songs to show the class “how it’s done.” Wiggins wasn’t familiar with the music.

“I felt that a very deep injury. I didn’t think I was showing up as a Black kid in the room,” she said. “We did not have those types of songs played in my house. I did not know those songs.”

Wiggins could not sing the song, and her halting embarrassment brought her to tears. Wiggins says she lied to her parents that evening when they asked her about her day.

She avenged her embarrassment a week later when the teacher let the class vote on what song would be played that day. Wiggins convinced her classmates to vote on the song “Dishonest Modesty” by Carly Simon, which contained profanity.

[adrotate banner=”55″]

The prank gave Wiggins and the other kids a good laugh, but left the music teacher shocked, overwhelmed and, ultimately, out of a job. Wiggins has come to regret the satisfaction she felt from the incident when she was young.

“It does make me realize that my path hasn’t been perfect,” she said. “My actions have not been perfect. I know this. And so that that’s why affecting a woman’s paycheck bothers me now.”

A recurring theme in Wiggins’ recent work is the concept of “economic lynching,” a term she coined to refer to “choking off the aspirations and the advancement of a person.” The concept became a concern in Wiggins’ later career. Her 2021 essay “Testimony on Economic Lynching in the U.S.” expounds on the concept.

Wiggins, a licensed boxing judge, notes Muhammad Ali, whom she interviewed in 1990, as an example of an iconic figure who endured economic lynching. In tandem with other stories of formative moments in her youth, such as when she vowed not to ask anyone for money again when her parents wouldn’t give her money for new bell bottom jeans, Wiggins points to an enduring purposefulness that has empowered her to endure her own struggles in this regard.

From the age of eight, she says, she knew she wanted to cover the Dallas Cowboys.

“I saw them on television, sitting at my father’s elbow on Sundays,” said Wiggins. “I saw this spectacle of football that just looked like a high art to me.”

MORE: Vino Caffeen’O offers roasted coffee from all over the world

She stayed true to the goal, studying for hours each day while in high school, earning her communication degree from Augusta University, then Augusta College. By 1999, she was, in fact, reporting on the Cowboys as a sportscaster with Fox 4 TV in Dallas. Before that, she had already been a reporter in Seattle, Memphis, Tenn. and, of course, Augusta at WRDW.

She has interviewed the likes of Michael Jordan, Kobe Bryant, Oprah Winfrey, Augusta’s own James Brown and, in 1988, Rosa Parks.

“That was and remains the most important thing that ever happened in my life,” said Wiggins about meeting Parks.

The title of her memoir is, in part, a reference to the Civil Rights Act of 1964, which is also Wiggins’ birth year. The book is a tribute to Parks, and to a moment Wiggins shared with the civil rights giant.

As a young reporter, Wiggins was compelled to ask Parks for a hug. Parks obliged. Wiggins was worried that perhaps she had exceeded the bounds of professionalism. But, as Wiggins notes in her memoir, the mother of the Civil Rights Movement embraced her as if her own mother. Wiggins could not help but notice their similar stature, cheekbones, and amid this hug, meeting heartbeats.

[adrotate banner=”15″]

She connects this with her own love for her hometown.

“So, now it’s almost 34 years since that day,” said Wiggins. “And like I said, my family is in my heart. You know, Rosa Parks heartbeat is here.”

While she postponed a recent flight back home near the end of the year amid concerns about the omicron COVID variant, she plans to make the trip soon. Wiggins visits Augusta regularly, in part, of course, to see her parents. The story of the music teacher was one she had to uncover, barely remembering it before preparing to write her memoir, as she tried to discern the most seminal moment in her life, when she decided, nurtured by the coaching of her father to “go places Black girls don’t go.”

“At age 12, I said something else, too,” said Wiggins. “I said that if people don’t see someone who looks like they look where they want to go, we are waiting for you. We are waiting for you.”

For more information about Nita Wiggins, visit her website at www.nitawiggins.com.

Skyler Q. Andrews is a staff reporter covering Columbia County with The Augusta Press. Reach him at skyler@theaugustapress.com.