(Editor’s note: This is the fourth story in a series by Dana Lynn McIntyre focusing on her Australia trip)

Australia’s Aboriginal tribes are an ancient culture dating back as far as 65,000 years according to the National Museum of Australia.

An organization created to preserve the Gumbaynggirr culture, the First Australians in the Coffs Coast area, found itself faced with two challenges.

First came the devastating bushfires that began in late 2019. That was soon followed by COVID-19.

“I was actually just talking with the cafe manager before coming here,” said Fiona Webb Lugnan. “She was saying that, yeah, the cafe was like the very first place to be shut down with the fires and with COVID as well.”

Lugnan’s brother, Clark Webb, is executive officer of Bularri Muurlay Nyanggan Aboriginal Corporation. It is based in Coffs Harbour, a coastal city about 350 miles north of Sydney.

The organization operated a coffee truck and cafe at Sealy Lookout, a popular tourist attraction that overlooks all of Coffs Harbour and the coastline. Although spared the brunt of the flames, smoke and the threat posed by the massive Liberation Trail fire in nearby Nana Glen, the cafe was forced to close.

MORE: Adventures Down Under: An introduction

All profits generated by the Nyanggan Gapi Cafe & Catering supported programs, including after school learning centres and language revitalization.

Lugnan said they were able to set up a temporary coffee van near their office location on Bray Street in Coffs Harbour. That continued income allowed them to be able to pay what are called “casual workers” in Australia. Those can be day workers or temporary employees who depend on having an income.

When COVID-19 arrived in Australia and lockdowns were put into place it meant the cafe at Sealy Lookout could not be reopened. However, Lugnan said that came as something of an advantage.

“So, during the COVID period, when everything was shut down, and they weren’t allowed to open up anything, that actually allowed for a complete restructure of the cafe business,” she said. “So, it’s got a permanent structure there. Now there’s a proper seating area. There’s electricity. Before it was run off a generator. So they’re able to do things that require freezing, you know, like milk shakes and stuff like that. So they’ve expanded that business.”

The construction projects at Sealy Lookout kept income flowing to the casual workers at a time when Lugnan says Aboriginal employment was particularly challenged.

Another challenge in Australia was one that was all too familiar in the United States with the arrival and spread of COVID-19, the educational system.

That included programs run in local schools by the corporation.

“Like cultural immersion programs with the students. Obviously, that had to be completely halted. So staff who were employed for those programs were kind of filtered into other areas,” Lugnan said. “They also completely halted our community language classes, that all went to zoom as most things did. The cultural programs turned into more of a home engagement program.”

A solution they found will sound quite familiar. It was much like one used in schools in America, including South Carolina and Georgia.

MORE: Adventures Down Under: Raging fires

“So, they put together packs and things like that for kids and families and delivered them to doorsteps. You know, just to keep that engagement and keep that connection with families,” she said.

The area around Coffs Harbour is similar to the CSRA, urban and suburban areas surrounded by large rural sections. Because of that their school’s faced many of the same challenges felt by school districts in Richmond, Columbia and Aiken counties. A number of their students had to be provided with laptops and similar technology.

A larger issue was students had no access to the internet. They distributed something they called “dongles”, we called it Wi-Fi on Wheels.

“But, if students were in those remote areas, it’s still difficult with the dongles, you still have to have something to pick up, so you know, it’s not a silver bullet, in a sense,” Lugnan said. “So, schools actually still provided the opportunity for students to be able to come in. Students who were completely isolated, kids with special needs or learning difficulties who weren’t able to learn from home or families weren’t able to provide that level of support. Schools were still providing very, very minimal supervision in order for the students to be able to come into those schools to continue to learn from there.”

Finding ways to educate students learning remotely or virtually was not the only struggle happening in Australia that sounds very American.

Healthcare professionals in Australia were also dealing with misinformation, lies and political rhetoric about COVID-19 and the vaccines.

“There was a reluctance from the community here for vaccination. I remember when it opened up for kids and Aboriginal Medical Service did a big drive for kids like five to 12 years old,” Lugnan said. “I took my daughter and there were people protesting and trying to tell people not to do it as we brought our kids. Lots of people who aren’t Aboriginal, older people who were trying to tell Aboriginal parents what to do with their kids, trying to tell them ‘Oh, you don’t do that, the government’s trying to control you.’ And I’ve never seen you before, you’ve never cared about our kids before.”

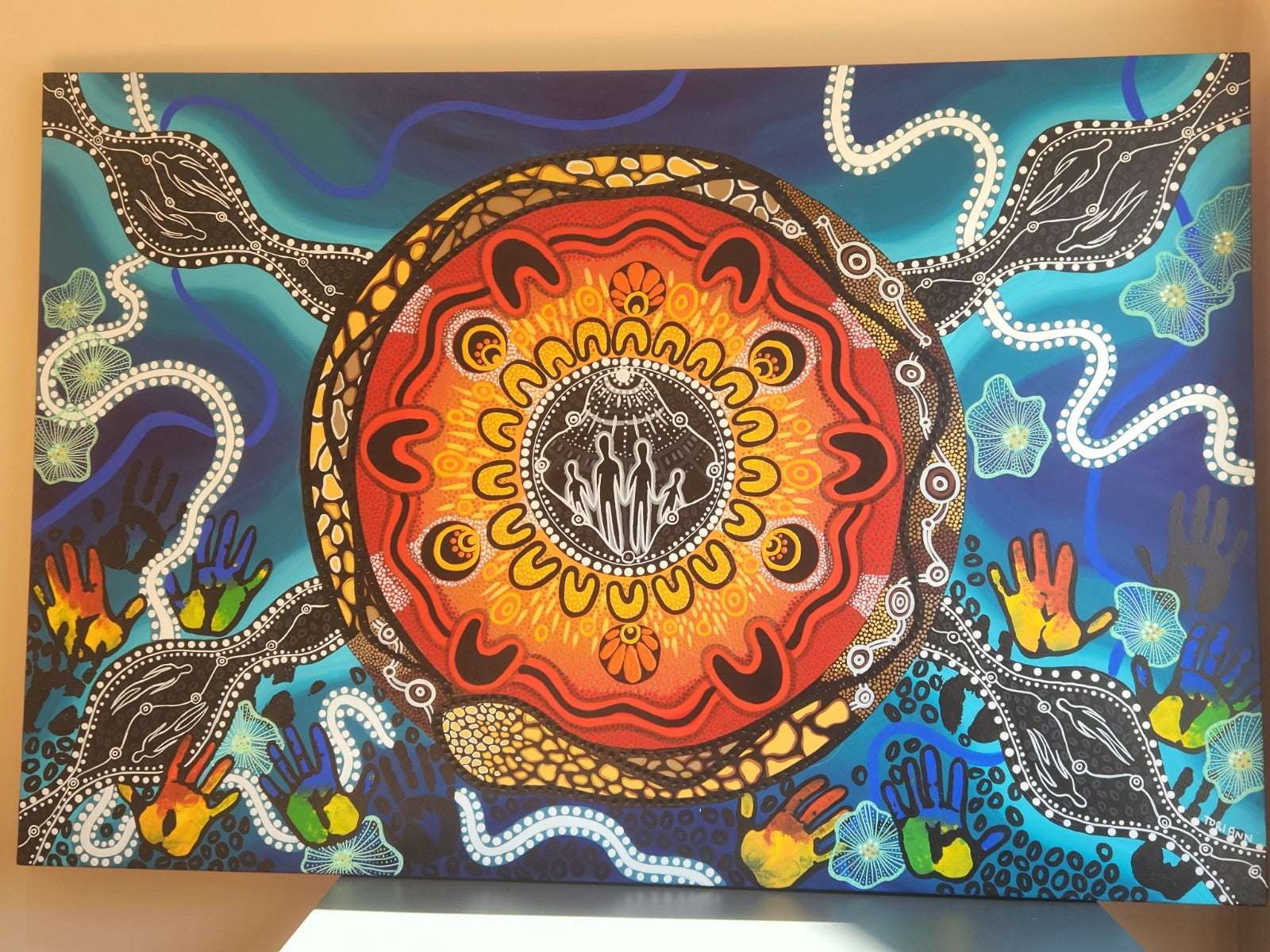

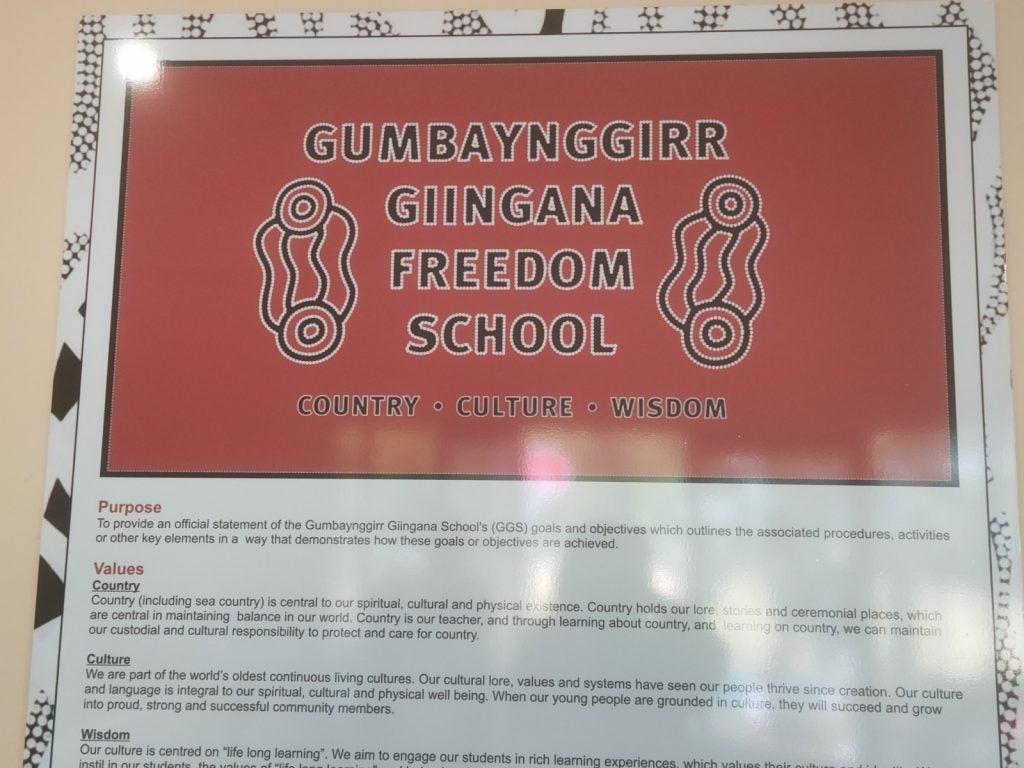

Despite the upheavals and challenges presented by COVID-19, BMNAC kept working toward one dream, the Gumbaynggirr Giingana Freedom School.

The school focuses on Gumbaynggirr language and culture, values and philosophies, with strong parental engagement. It is also the first bilingual school of an Aboriginal language in NSW.

MORE: Adventures Down Under: The village of Nana Glen emerges from the fires and COVID-19

It opened for students in January 2022 for students from K- 2 with approximately 15 children enrolled for the first year. It will eventually expand to K-6.

Fiona Lugnan will join the staff in 2023 to prepare to welcome the next grade levels.

“I’m really proud to be connected to this organization and I think, during the fire season and through COVID, it’s proven that it’s been a leader in community, not just the Aboriginal community but in Coffs Harbour as well and wider region,” smiled Lugnan.

Life is improving for the Coffs Coast region, but it is not so everywhere.

Outside of Wollongong, about 50 miles south of Sydney, a sanctuary trying to preserve one of Australia’s native animals continues to struggle after being destroyed by the bushfires. We’ll take a look at Bargo Dingo Sanctuary in our next installment.

Dana Lynn McIntyre is a general assignment reporter for The Augusta Press. Reach her at dana@theaugustapress.com