The Augusta Jewish Museum, in partnership with Kennesaw State University, unveiled on June 18 a new World War II traveling exhibition titled, “World War II: The War That Changed the World.”

The exhibition was opened to a packed gallery.

The exhibit addresses the Holocaust in grim detail, but the exhibit as an whole illustrates the lives of people from all walks and creeds who were caught in the crosshairs of the world’s deadliest war and its aftermath.

The exhibition was created through oral histories compiled by the Museum of History and Holocaust Education at Kennesaw State University.

Adina Langer, curator of the Museum of History and Holocaust Education, was on hand via Zoom to highlight some of the stories found in the collection.

“World War II was a pivotal moment that fundamentally changed the role of the United States in the world,” Langer said. “We look at people’s country of origin, their role in society and how the war impacted them.”

Many of the people featured in the exhibit are dead, but their stories live on. Among those are:

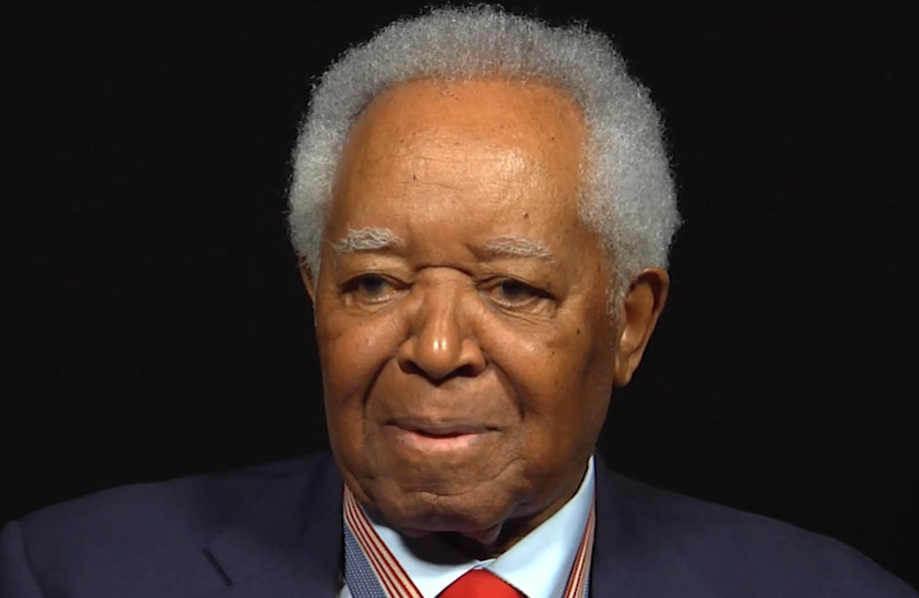

Theodore Britton recalled growing up in New York City and having to work along with his parents to survive.

“I worked one job before school and then three jobs after school,” Britton said.

When America entered the war, Britton would go from being a shoeshine boy to being referred to as “boy” in a segregated American military. Britton joined the first African American Marine Corps regiment, the 51st Defense Battalion, where he served honorably and was later appointed as ambassador to Barbados and Grenada by President Gerald Ford.

Herbert Kohn remembered his childhood in Frankfurt, Germany as being idyllic until Hitler came to power. The first indication that something was terribly wrong was when he was expelled from school for being Jewish.

Kohn recalled the night of Nov. 9, 1936, when members of the Nazi Sturmabteilung paramilitary, or stormtroopers, replete with their leather chest straps, jack boots and swastika arm bands, banged on the family’s door demanding to see any male in the house between the ages of 16 and 60.

It was Kristallnacht, or the “night of broken glass” in Germany.

Kohn was 11 at the time and his grandfather was well over 60, but his father, a distinguished World War I veteran, was 38 and so he was dragged off by the Nazis.

“He came back three weeks later after suffering unspeakable abuse, his hair had turned white and he had lost over 30 pounds,” Kohn said.

The family fled Germany, first traveling to England before immigrating to America. Kohn’s family was lucky as there were strict immigration quotas for Jewish people seeking asylum, according to the U.S. Holocaust Memorial Museum.

Near the end of the war, after he came of age, Kohn joined the U.S. Army. He eventually attained the rank of lieutenant colonel as a reservist.

Jimmy Doi faced a horrible dilemma. An American born of Japanese descent, Doi’s parents had moved back to their home village on the outskirts of Hiroshima before the war and Doi remained in the states because he did not speak Japanese and wanted to finish high school where he was a noted athlete.

Doi recalled being ostracized by fellow students after the Dec. 7, 1941 bombing of Pearl Harbor and was later forced into a Japanese internment camp. In 1944, Doi was drafted into a segregated U.S. Army regiment comprised of only Japanese Americans and served in the mountains of Italy.

“Staying up in the mountains in the snow, our socks were always wet, and one day I looked and I saw black spots on my left toe, and so I went [to a hospital]. That’s pretty good; I stayed and at least we got a hot meal. While we were up there we were eating nothing but K-rations,” Doi said.

Fear and dread fell over Doi when he learned of the atomic bomb attack on Hiroshima; he learned later that his parents had survived, but most of his extended family died in the attack.

These are but a few of the stories from what journalist Tom Brokaw dubbed the “greatest generation of the 20th Century” that are highlighted at the exhibition. As President Franklin D. Roosevelt said, they were a generation that had a “rendezvous with destiny.”

The exhibition is free to the public and is open Fridays through Sundays from 12 p.m. to 3 p.m., June 23 through August 11. The Augusta Jewish Museum is located at 525 Telfair Street in downtown Augusta.

Scott Hudson is the Senior Investigative Reporter and Editorial Page Editor for The Augusta Press. Reach him at scott@theaugustapress.com