Some residents of Columbia County have received a letter inserted in their water bill, leading many to speculate on social media that their tap water may be contaminated with “forever chemicals.”

Officials with the county say the letter is a mere formality and that county supplied water is safe to drink.

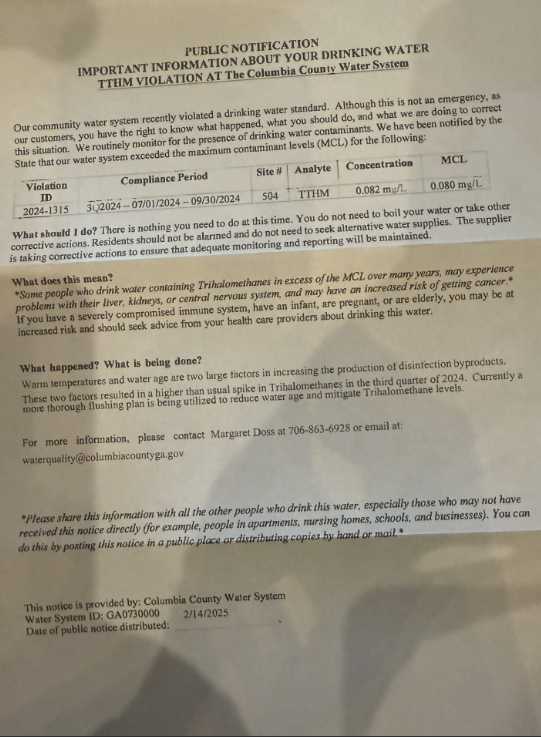

Moreover, the letter sent was a form letter crafted by the Georgia Environmental Protection Division (GEPD), and contained some technical jargon crafted by that state agency that might be confusing to the average reader. In reality, Columbia County officials say, the “violation” mentioned was minor and there was never any danger to the public.

Despite some fear in the community, the letter sent to residents was not referring to “forever chemicals,” or polyfluoroalkyl substances, PFAS, which, according to the Environmental Protection Agency, are chemicals used primarily in plastic product packaging and cannot be broken down by the body’s digestive system.

What was found in recent routine water sampling were trihalomethanes, which are organic matter that are only dangerous if ingested at very high levels over decades.

According to Environmental Compliance Manager for the Columbia County Water Utility Department, Margaret Doss, the county uses chlorine to sanitize the water and remove biological toxins. The letter, sent to residents at the direction of the GEPD, notes that the presence of “trihalomethanes” were slightly elevated during the last round of testing.

Columbia County is required to test for the amount of these chemicals in the treated water at eight sample sites throughout the county on a quarterly basis, that amounts to 32 samples taken each year, Doss says.

“Total trihalomethanes are a byproduct of the chlorine disinfection process the county uses to protect its customers from waterborne illnesses like amoebic dysentery, cholera, and typhoid fever,” Doss said.

Even though the trihalomethane levels were only slightly over the limit of 0.08 parts per million, the county is still obliged by GEPD to notify the public of the sample findings.

According to Doss, the samples with elevated trihalomethane levels were found in mainly rural areas where the water sampled was warmer, allowing for organic growth.

“We have revised our flushing schedule to assist with reducing the age of the water in the rural parts of our system. We are also in the process of exploring longer-term solutions,” Doss said.

Scott Hudson is the Senior Investigative Reporter, Editorial Page Editor and weekly columnist for The Augusta Press. Reach him at scott@theaugustapress.com