(Disclaimer: The opinions expressed in this column of those of the author and do not necessarily reflect those of The Augusta Press.)

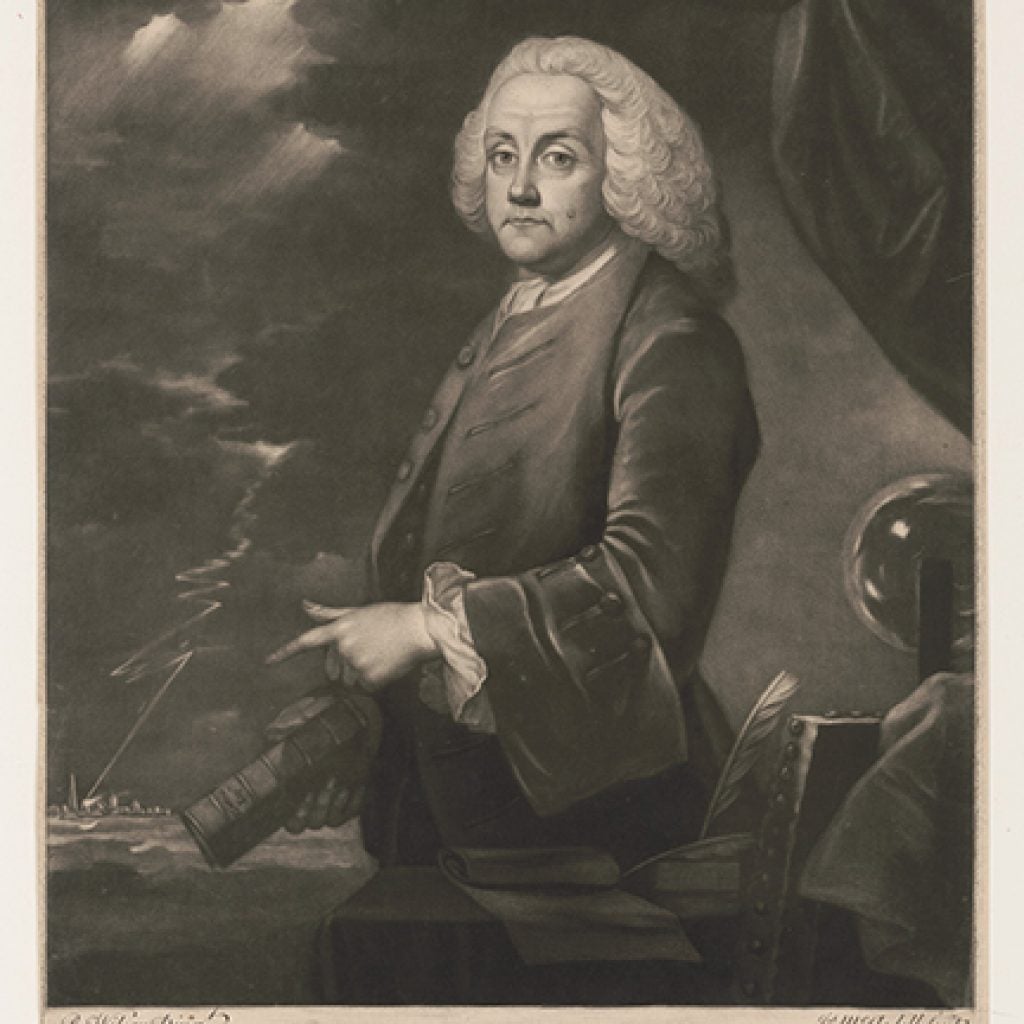

“A Republic, if you can keep it.” -Ben Franklin

On September 18, 1787, the Constitutional Convention had just ended. Ben Franklin was asked if he thought we would end with a republic or a monarchy. His response was, “A Republic, if you can keep it,” a reply based most likely on his known fear that the newly created office of president could evolve into a form of monarchy. Franklin was both brilliant and far-sighted. The presidency has indeed become a kind of elective monarchy. Few people seem to mind. But this July 4 holiday season, I wanted to write about something I consider a far more insidious threat to the survival of this republic.

portrait by Benjamin Wilson. Courtesy Library of Congress.

Before I get to the “bottom line,” however, I would like to dispense with a question that keeps cropping up: the argument about whether we are a republic or a democracy. The two are not opposites. One can have a democracy without a republic (Britain), or a republic without democracy (Russia), neither (Saudi Arabia), or both (most of Europe and the Americas). Democracy has existed here since the founding of the United States, and even in colonial times, although voting rights did not become truly universal until the 1960s. The United States is and always has been a democratic constitutional republic, and therein lies the danger to our future. Take away any of those three words, and we cease to be America. But where does the danger lie?

Many Americans today are worried about the polarization of our citizens. That is not the greatest danger, however. In fact, here is the good news: polarization is as American as apple pie. For most of our history, the country has split into oppositions that have denounced each other with Biblical fervor. During the election of 1800, pro-Thomas Jefferson papers called his opponent John Adams “blind, bald, toothless, and of being a hermaphroditical character,” and of importing mistresses from France; Adams partisans went even further, claiming that murder, robbery, rape, adultery and incest would be openly taught and practiced if Jefferson won, and that the soil would soaked with blood and dwellings would be in flames. Female chastity would be violated, and children would wind up writhing on pikes. In fact, one pro-Adams newspaper even compared Jefferson to the Antichrist. So much for a calm, issue-focused election.

Why was this so – then and now? Many years ago, I was asked by a local church to give a lecture about the Bible in American politics. I think they were expecting me to talk about how one party followed the Bible and the other didn’t. Instead, I gave a presentation that focused especially on the lasting influence of the Puritans on how our religious history and how that history leads us to turn every political issue into a moral issue. If you view an issue as moral, then the other side must by definition be regarded as immoral, and therefore evil. This is why on many “big” issues in our history, compromise has been impossible. Take for example an issue that does have moral content, the fight over abortion. The two “sides” refuse to even call the other “side” by its given name; Pro-Choice calls Pro-Life “anti-choice,” and Pro-Life calls Pro-Choice “pro-abortion.” Polarization is the American Way.

Beyond polarization, the real threat lies in how more and more people across the ideological spectrum are regarding the Constitution. The writers of our Constitution were a remarkable group. They were a highly educated, thoughtful group, as close to having a room with philosophers and political scientists present as we have ever had. They had first tried having a loose association of sovereign states under the Articles of Confederation, but that was failing, and so they met in Philadelphia and performed the rather complicated task of creating a truly united nation while preserving the role of the states. The fact that it was a relatively small group representing the powers in almost every state made it possible for them to have their document accepted, although ratification took time and required the addition of a Bill of Rights. What mattered more was the growing reverence in which the document was held; this became the glue that held America together in times of crisis.

This can be seen during two of the periods of greatest crisis that this country ever experienced. At first glance the Civil War seems like a failure of the Constitution. However, the country did not split into two organically different countries but into two countries with surprisingly similar constitution. The Confederates never believed that they were revolting against the Constitution. The Confederate version did have some differences (most notably the many explicit protections of slavery) but was basically the same. The war resulted from a different interpretation of whether the Constitution allowed a state to secede unilaterally. This had not been thought of originally because as late as the 1820s, it was considered an cardinal sin to even think about secession, let alone mention it. The issue had to be settled in battle. This is probably why Socialist Rev. Edward Bellamy included the word “indivisible” when he wrote the Pledge of Allegiance. (For you legal trivia buffs, the states CAN meet and dissolve the union, but through the constitutional amendment process).

The second crisis came in the 16 years during which the United States experienced the Great Depression and World War II. Remarkably, the Constitution came through this age largely unchanged. The only amendment was the abolition of prohibition. President Franklin Roosevelt proposed adding seats to the Supreme Court to make the body less conservative (the Constitution does not specify the number), but this was considered highly offensive even by Americans struggling for economic survival. One comparison always fascinated my students. The Great Depression led Adolf Hitler and Franklin D Roosevelt to become heads of their respective governments in January 1933. They both died in April 1945. The U.S. government and Constitution were not significantly changed, other than the addition of Federal agencies to address the crisis, and later, to win the war. The existing German government and laws were abolished and replaced with a partisan Nazi state. Why? One factor: in the United States, we had had a Constitution revered by the country as our foundation; in Germany, the Republic was only 19 years old when Hitler came to power – and it was a very unpopular system at that. (One other difference; Hitler wanted to conquer the world; Roosevelt pretty much did. But that’s another column.)

Let’s be fair. There have always been Americans who regarded the Constitution with much less enthusiasm. Plenty of examples, but the one that comes to mind is that of Pennsylvania Congressman Thaddeus Stevens, a unique man in that he was for true racial equality back at the time of the Civil War. He once told an associate that the document was just a “worthless bit of old parchment.” Stevens was responding to the failure of the original document or the Reconstruction amendments to abolish slavery or provide true minority rights. Stevens was right; the men of 1787 could hardly risk the slave states walking out of the door, and there were those who expected slavery to disappear peacefully (the cotton gin, which vastly increased the profitability of slavery, was still years away). It would take the Union’s long blue columns to destroy the slave system.

Even so, the Constitution is both this country’s foundation and the glue that binds it together. This would not be true if Americans cease to revere the document, and there is increasing evidence that this is happening.

- On the Left, there are increasing references to the authors of the document being a bunch of old white male slave owners who could not have been familiar with modern issues and problems. The Constitution is seen as a barrier to progressive change and modernization.

- On the Right, professed adoration of the Constitution cannot be taken seriously after January 6, 2021. The extreme Right adores a Constitution that does not exist.

Can we write off the rantings of extremists? No, we cannot. Majority rule is historically a rather dubious concept; in fact, history is often made by minorities. The Reformation in the Netherlands was achieved by zealous reformers (well, who else) who maybe were only 3% of the population. In all of Russia, there were only about 10,000 Bolsheviks at the time the monarchy fell; eight months later, they controlled Russia. Democracy cannot prevent this. For one thing, freedom of expression, without which democracy does not exist, makes it easier for extreme groups to communicate and recruit. Second, extremists always vote, while many people who are less extreme stay home. Everybody complains about Congress – but in some national elections ¾ of the people do not bother to vote.

The future of the Constitution is uncertain. What is certain is that a decent replacement could never be constructed now. It would take a long time to be accepted, so that we might wind up in a period with constant constitutional change. Individual and institutional rights could disappear. More importantly, the national capacity to write one does not exist. Here is where polarization does play a role. Republicans control the Electoral College while Democrats control the “national popular vote,” and in the current atmosphere, a meaningful compromise in as economical a wrapper as the Constitution is will not happen. In addition, too many Americans do not understand the Constitution or perhaps even care about what it actually says. Our civics education is garbage, and our STEM focus has only made it worse.

One closing note. Could controversies involving the Supreme Court affect the credibility of the Constitution, and the tolerance for one group or another for our constitutional system? The short answer is yes, although so far only once has it led to a truly massive crisis. Around the 1960s, a number of Supreme Court decisions left conservatives foaming at the mouth; in the 2020s, it appears it will be the liberals’ turn. In 1857, the Supreme Court issued the Dred Scott decision, which among other things declared that Mr. Scott was a slave even if he was in a free state. This ended Congress’ ability to draw compromise lines across the power. Chief Justice Roger Taney told a friend that he feared the decision (which he wrote) might lead to civil war. It did.

I hope you had a happy 4th.

Hubert P. van Tuyll, J.D., Ph.D., is a professor emeritus of history at Augusta University.