In 1789 King Louis XVI of France was seriously short of money. The Palace decided to call together a convention of the Estates, the representatives of France’s three social classes (clergy, nobility, commoners). It didn’t end well. Instead of more tax money, the King got a revolution, and in 1793, the death penalty. This was the same time that America finished ratifying its magnificent Constitution.

This passed through my mind when a friend sent me a call for a “Convention of the States,” a constitutional convention called by the state governments. It’s interesting that we’ve only had one true Constitutional Convention. (Yes, I know about the one written in Montgomery in 1861, but it only applied to part of the states, it only lasted four years, and it was pretty much the same as the original, apart from a lot more language about slavery.) Why not more?

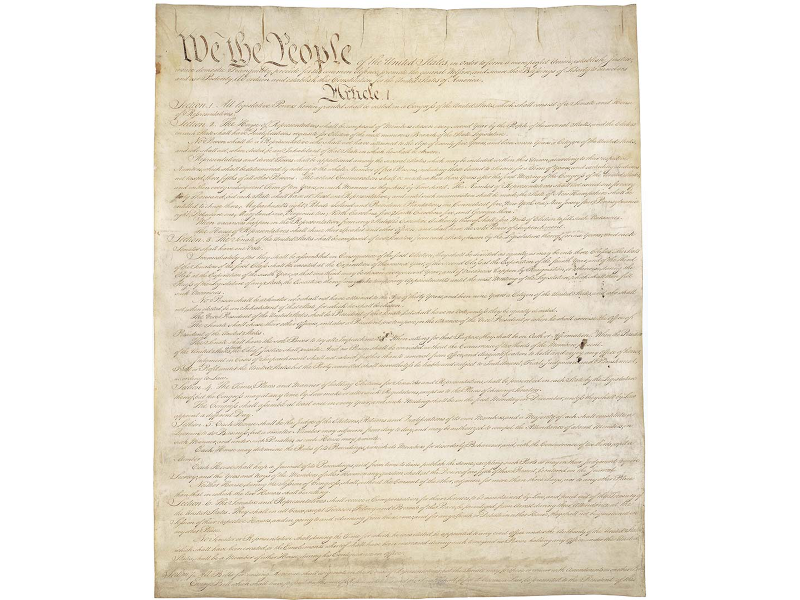

Any national meeting that can make or propose fundamental changes is unpredictable. Trying to limit it to any particular purpose might not work. Ask Louis XVI. (Well, you can’t.) But another example would be – our own! The Philadelphia meeting in 1787 was called for the specific purpose of amending our original governing document, the Articles of Confederation. That dated from the Revolutionary War and was pretty much a flop. By leaving each state sovereign, it created a pseudo-country that could not deal with either foreign or domestic problems and was on the brink of collapse. The Founding Fathers amended the Articles alright – straight into the trashcan! They decided to write a brand new Constitution from scratch.

[adrotate banner=”23″]

How did they get away with it, you ask? Well, several things. First, there was a general consensus that the Articles weren’t working. Second, all the states ratified the new document, which prevented any legal questions about the legitimacy of the new document. Finally, just look at the list of names who were present at that meeting in Philly. In one room were Washington, Franklin, Adams, Madison, Hamilton … oh, I could drop more names, but here were the heavy hitters of early America.

But why was there never another convention? No one working on the document in 1787 intended it to be set in stone. However, there is plenty of evidence that, broadly speaking, Americans have been satisfied with the overall Constitution. As mentioned above, secession did not produce a radically different document. The greatest 20th century time of crisis – the Great Depression and World War II – produced hardly any change in the Constitution at all. A bigger reason is that, up to a point, we have an ongoing constitutional convention; Congress is authorized to propose amendments. So far, 27 have been added to the Constitution. (I said “up to a point” for a reason: I do not think that the Founding Fathers had any intention for Congress to propose an entirely new Constitution, and it never has.)

Yet, the Constitution clearly allows for the calling of a Convention, although, interestingly, Congress may not do it unilaterally. Article V provides that “Congress … on the Application of the Legislatures of two thirds of the several States, shall call a Convention for proposing Amendments . . .” Simple enough. Yet, in the 231 years since Rhode Island became the last state to ratify the document, it’s never happened.

[adrotate banner=”19″]

Popular satisfaction with the existing Constitution is only one reason, in my opinion. First, there is nothing that establishes that such a Convention can be limited to proposing 1, 5, or 12 specific amendments, or indeed a whole new Constitution. This is the equivalent of opening Pandora’s Box, lifting the lid of a can of worms, etc. (Yes, the states still have to ratify, but at that point, more than 300 million Americans would be at the mercy of the wisdom and intellect of their state legislatures.)

Another reason is that the calls for a Convention come from the extremes. At the moment, they come from the Right, but that could easily be the opposite in the future. Ideologues tend to have the least respect for process and existing legal and constitutional structures. That is why dictatorships like the Soviet Union and Nazi Germany specifically subordinated judicial process to their respective ideologies. Our original Constitution Convention was not driven by a particular radical ideology, but by the desire to build a functioning country.

Which brings me to my biggest issue. The success of our Constitution is in large part because of the kind of people who wrote it. The Founding Fathers were a group of highly educated, intellectual, 18th-century gentlemen, who understood political philosophy and could real debates about it. Historically, this was a unique moment. I don’t see many James Madisons around, especially in public life. So, I say, by all means amend, if you think it necessary, but don’t risk our whole Constitution in the process.

A Convention might just do that.

Hubert van Tuyll is an occasional contributor of news analysis for The Augusta Press. Reach him at hvantuyl@augusta.edu

[adrotate banner=”43″]