Editor’s Note: Sandy Hodson’s 14-part investigation begins today into how justice has been administered by Glynn County law enforcement and the Brunswick Judicial District. Series stories will be published on Sundays and Thursdays.

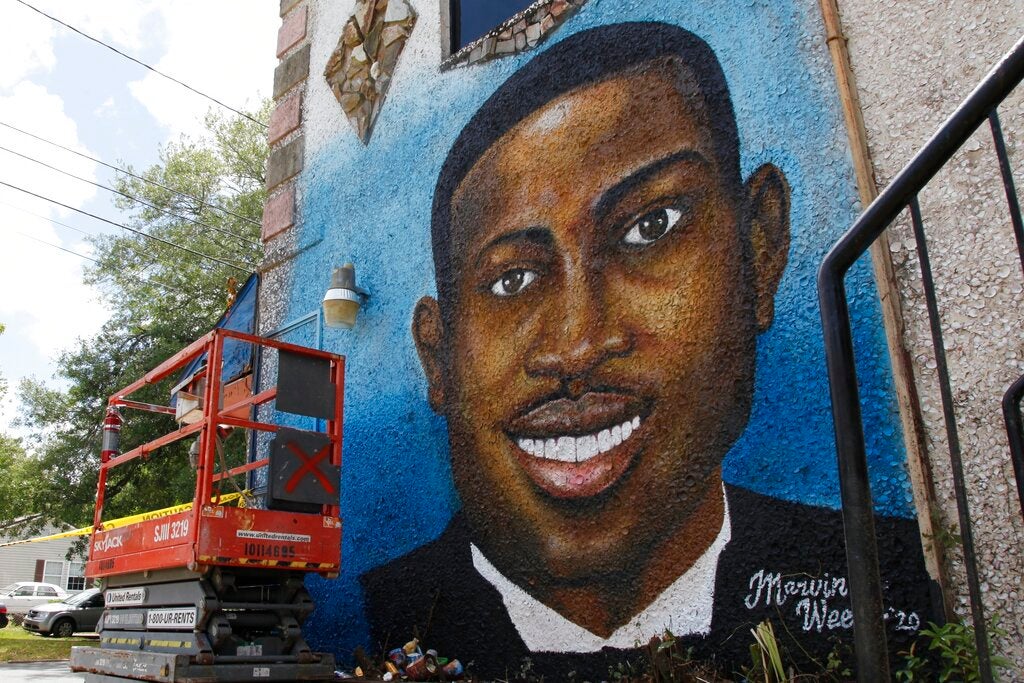

If the Glynn County Police and district attorney had had their way, the three men who killed Ahmaud Arbery would have gotten away with murder.

Arbery was raised in Glynn County, but his mother, Wanda Cooper Jones was raised in Burke County. When the protests began after the killing of George Floyd, in addition to speaking out and fighting for justice for her son, Jones attended marches here in Augusta and across the country.

Golden Isles Injustice

Part 1

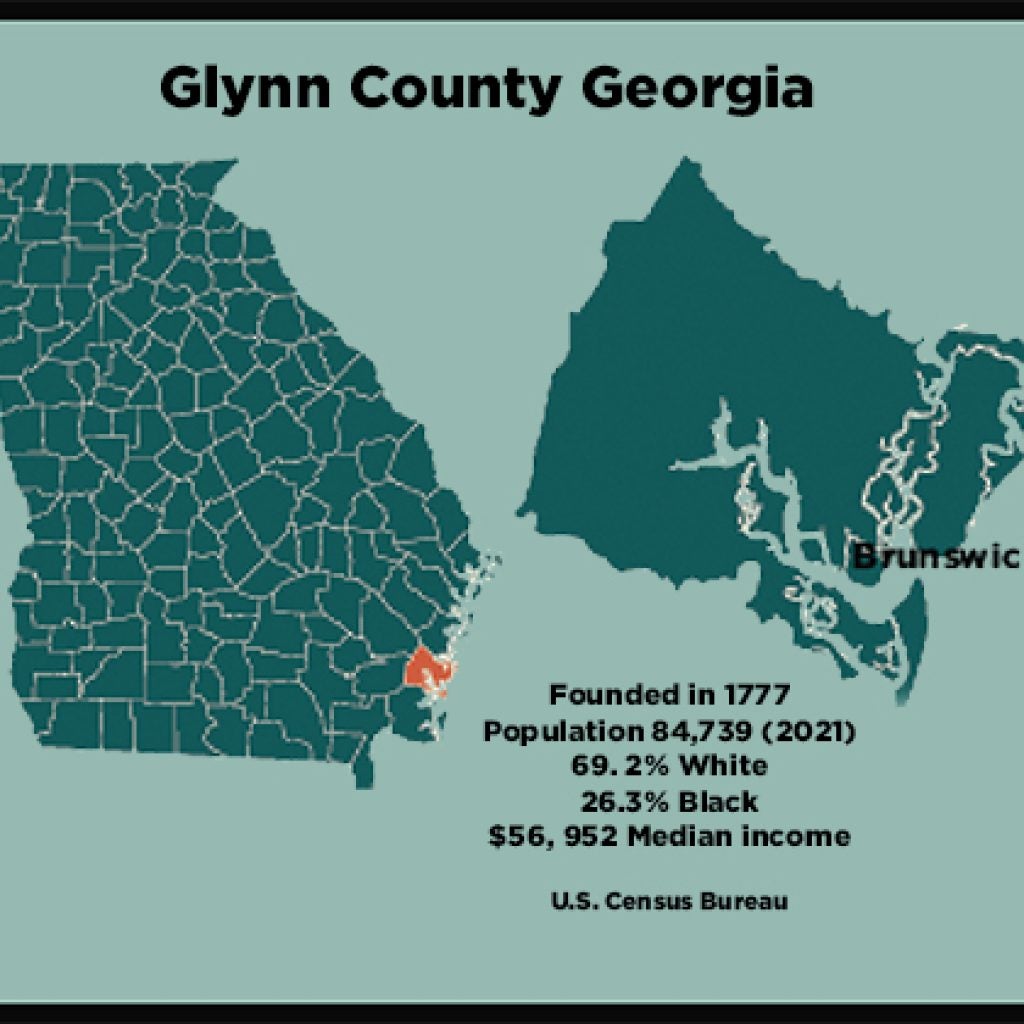

By bringing her son’s story to our community, Wanda Cooper Jones also brought a compelling story of corruption that extends not just to the Glynn County law enforcement but also to the county’s judicial circuit which is a part of the U.S. District Court for the Southern District of Georgia. That’s the federal district court based in Savannah but that also has a satellite in Augusta.

The connections between the Augusta area and coastal Georgia are what first brought the situation in Glynn County to our attention, but this series is also motivated by a belief in the truth of Martin Luther King Jr.’s words: “Injustice anywhere is a threat to justice everywhere. We are caught in an inescapable network of mutuality, tied in a single garment of destiny. Whatever effects one directly, affects all indirectly.”

Now that Greg and Travis McMichael and William “Roddie” Bryan have been convicted and sentenced in state and federal courts for the 2020 murder of the 25-year-old runner Arbery, a brutal crime described by many as a lynching, it may be hard to believe that the McMichaels and Bryan weren’t charged until weeks later. Those charges were not levied, however, until new law enforcement and prosecutors were brought in to replace the Glynn County authorities.

The way authorities handled Arbery’s murder is what has passed as justice for decades in the Brunswick Judicial Circuit. The people entrusted to enforce the law and bring justice to the community have repeatedly made a mockery of the criminal justice system, through intention, incompetence or indifference.

Those with money and power can act with impunity; solving crime in a search for justice has had less to do with “what happened” than with “making somebody, anybody” pay.

This is what happens when those in power no longer believe the rules governing the criminal justice system matter. Without the rules of law, the most basic function of the criminal justice system, sorting the guilty from the innocent, fails, said Stephen Bright, Yale Law School professor and the founder of the Southern Center for Human Rights. Bright is a veteran capital murder defense attorney who may have practiced in more Georgia Superior Courts than any other attorney.

Wrongful convictions can happen anywhere. Since 1989, 2,263 people have been exonerated in the United States – cleared of crimes based on evidence of actual innocence, according to the National Registry of Exonerations. Two of those cases happened in the Brunswick Judicial Circuit.

This investigation by The Augusta Press has uncovered evidence that the men wrongly convicted in those cases, Dennis Perry and Larry Lee, likely aren’t the only ones wrongfully convicted of murder in the most southeastern section of Georgia that composes the Brunswick Judicial Circuit. The Press has found that what happened in Perry’s and Lee’s cases has happened again. And again. And again.

This series is about what The Press investigation found. It’s not new ground for a number of talented journalists, investigators and attorneys who worked on these cases and incidents in the Brunswick Judicial Circuit. But when these cases are combined and compared, a pattern emerged that many in the legal community have long suspected. Here’s where the story starts:

Larry Lee

Larry Lee’s case is notorious in the Georgia legal community, at least among those who practice criminal law, because of an opinion written in 2008 by a conservative, elder Superior Court judge from Tift County, another rural area of Georgia.

Chief Judge Gary Clinton McCorvey’s 145-page opinion, which includes an additional 43 pages of endnotes, ripped into the criminal justice system in the Brunswick Judicial Circuit in no uncertain terms.

McCorvey described what happened in Lee’s case as “more akin to the Nazi SS investigations than those required by the laws of this state and nation.”

On the morning of April 26, 1986, Clifford and Nina Jones were home with their 14-year-old son Jerold, after their daughter Christi, left on a trip to the beach. Between 6 a.m. and 8 a.m., the three were savagely beaten and shot to death. Lee was convicted of their murders and sentenced to death in November 1987.

It wasn’t until 2000 that pro bono attorneys working on Lee’s case uncovered the fact that significant evidence had been withheld from his original defense. The Georgia Supreme Court ordered a hearing on Lee’s habeas corpus petition, but it was another six years before they could get hearings before Judge McCorvey.

The Jones family lived in Wayne County and ran a popular restaurant there. The killings sent shock waves through the rural county of approximately 30,000. Wayne is one of the counties in the Brunswick Judicial Circuit. The district attorney then was Glenn Thomas who held office for 30 years.

“He had a ‘who done it’ in Wayne County where he lived,” said David Dowdy, a Glynn County Police detective who arrested Lee not for the Jones family slayings but in a different case – the killing of Charles Moore on June 17, 1986. Moore was fatally shot when he and neighbor walked into his home during a burglary.

Lee’s brother, Bruce Lee, shot Moore, 44. The neighbor fired six times at Bruce Lee, killing him with a shot between the eyes, Dowdy said. Larry Lee ran and eventually hooked back up with Sherry Lee, his sister-in-law who was serving as the driver. They hightailed it back home to Savannah.

Dowdy had a dead resident and a dead stranger who wasn’t carrying anything that day but a gun. Dowdy put his picture out to the surrounding areas, including Savannah. Fingerprints proved the stranger’s body was Bruce Lee.

Dowdy got a search warrant for the Lee brothers’ Savannah apartment. His partner at the time was Carl Alexander who would go on to became police chief and who died in 2021. Dowdy believes that Alexander put out the lie that bloody towels found in the Lees’ apartment were linked to the Jones family murders. But there were no bloody towels in the apartment during the search, Dowdy said.

The Jones murder investigation was a circus with half the people in the county going through the crime scene, Dowdy said. Blood evidence was stored in plastic bags where it rotted.

Dowdy couldn’t find Larry Lee at first, but he had his brother’s body, and he told the Lees’ mother she had to give up Larry’s location to get Bruce’s body. He, Greg McMichael and a GBI agent went to Flagstaff, Ariz., to pick up Lee. The GBI agent wanted to questioned Lee about the Jones family murders, and he bought crimes scene photos to show Lee, Dowdy said.

“Larry got sick just looking at the photos,” Dowdy said. “He told them, ‘I confess, I was there (when his brother killed Moore) but I did not have anything to do with the Jones family slaughter right here.’”

McMichael would become the chief investigator for the Brunswick Judicial Circuit district attorney’s office, a position he had recently retired from just before he and two others gunned down Ahmaud Arbery on Feb. 23, 2020. One of the young assistant district attorneys who worked on the Jones family murders and helped convict Lee was Stephen Kelley. He would follow Glenn Thomas and serve as district attorney for 14 years before he was appointed to a Superior Court judgeship, a position he still holds.

Although there were 47 latent prints found at the Jones family home, none matched Larry Lee or his brother. Larry Lee and his sister-in-law insisted they knew nothing about the Jones’ murder.

But in her fourth statement, after she was promised immunity and money, Sherry Lee changed her story. Investigators also had evidence that showed Bruce Lee had sold a gun to a cousin in Augusta a month after the Jones family killings. Jones had many guns at the family home. And an informant, who was inside the Glynn County jail where Larry Lee was held, said Lee confessed to him.

It would take 26 years before the extent of the corruption of Larry Lee’s case was exposed.

Although prosecutors made much of the gun Bruce Lee sold to his Augusta relative just after the Jones family murders, they knew no weapons were taken from the Jones home. Jones had meticulously listed every weapon he owned for insurance purposes, and the list turned up during the murder investigation, according to evidence presented during the habeas hearing for Lee.

The defense was never informed – as rules of evidence require – that the jailhouse informant had previously testified against others and that his aggravated assault charge would disappear in exchange for his testimony during Lee’s trial.

The defense also didn’t know that a witness at trial changed her story about the color of a car she saw near the Jones’ home on the morning of the murders. Initially, she said the car she saw was white. Later, she said the car had been blue, the color of the Lee brothers’ car.

And the defense didn’t know about a police statement given by another neighbor who said he saw two vehicles near the scene, neither of which was a blue car. That police statement was also hidden from Lee’s trial attorney, evidence presented during the habeas hearing proved.

Lee’s defense team for the habeas petition also discovered that the district attorney instructed a crucial witness, the Jones’ daughter, to lie about certain details.

“I did exactly what Mr. Thomas told me to do,” she testified at Larry Lee’s habeas hearing years later.

But maybe what was most astounding to the judge presiding over Larry Lee’s habeas hearing was that evidence two other men, also brothers, may have killed the Jones’ family was not only withheld from the defense but ignored.

Dowdy said he got a tip about the Jones’ case at a family gathering in Wayne County. A relative of his wife’s told him she believed Joseph Thomas and Robert Andrew Yarbrough killed the Jones family. They had killed Glenda Ann Strickland the morning of March 9, 1987, as she drove to her job at a convenience store with a bank bag of cash. Because it wasn’t his case, Dowdy passed the tip on to Wayne County Sheriff investigators, the GBI and the prosecutors.

“They shit canned it,” Dowdy said.

The Yarbroughs finally were investigated for the Jones family murders, but not by law enforcement; by Larry Lee’s pro bono defense team. The Yarbrough brothers worked at the Jones home shortly before the murders. They knew Clifford Jones kept cash and checks in the home safe, and the brothers also knew that Jones would have the restaurant receipts from the night before. Lee’s team found a witness who heard Joe Yarbrough say he was “going to get” Clifford Jones for allegedly refusing to pay for work the Yarbroughs did for him.

There was more “substantial” evidence, the judge wrote in Larry Lee’s habeas order in 2008. The Yarbrough brothers had vehicles matching the description the secreted witnesses said they’d seen the day of the murders. After the murders, Joe Yarbrough had scratches on his arms, neck and face. He left home that morning at 5:30 a.m. and wasn’t seen until the next day. He also unexpectedly had money and bought out-of-the-ordinary, expensive gifts. A bloody boot print, a possible combat-type boot print, was found at the Jones home. Robert Yarbrough was in the National Guard, a fact known to the GBI agent assigned to the Jones case.

As the habeas team prepared Larry Lee’s petition in part by filing Open Records requests with the district attorney and others, Assistant District Attorney John B. Johnson called the GBI to tell them to dispose of evidence from the Jones murders, it was revealed in the habeas hearing.

LEE ButtsFinalOrder2008 by augustapress on Scribd

McCorvey granted Lee’s habeas petition on April 28, 2008, but years passed before the case moved further. The state appealed. When that failed, they asked the judge for permission to present the testimony of two trial witnesses – whose pretrial statements were withheld from the defense at the original trial – by simply reading that testimony into the record. Both witnesses had died. One was Sherry Lee, the co-defendant granted immunity. Sherry Lee was having sex with at least two sheriff officers while incarcerated, according to the habeas order.

“The state had the opportunity to prosecute this case in a manner that would have allowed the jury to properly weigh Ms. Lee’s credibility. The state squandered that opportunity by violating basic procedural rules which were enacted to ensure that every citizen accused of a crime receives a fair trial. (Lee) has been denied the right to confront the most significant witness against him with her prior inconsistent statements, which the state wrongfully failed to disclose.

“The state cannot benefit from such misconduct,” Judge E.M. Wilkes III wrote Feb. 19, 2015, in denying the prosecutor’s attempt to put the tainted evidence before a new jury.

Months later District Attorney Jackie Johnson, who had announced she would retry Larry Lee and again seek a death sentence, moved to dismiss the Jones family murders case against Lee.

In her seven-page motion, Johnson never mentions Sherry Lee’s withheld evidence or any of the other prosecutorial misconduct. Instead, she boasted about Sherry Lee’s incriminating statement – how she drew a map of the route they took to the Jones’ home, that she drove the silver Mazda described by a witness – a trial witness who had actually testified the car was blue, like the Lee brothers’ – and Johnson wrote that “Investigators were able to corroborate specific portions of Sherry Lee’s statements with other witnesses and evidence in the case.”

In addition, Johnson wrote, during the return trip from Arizona to Georgia, Larry Lee “made certain statements to the GBI agent … tending to incriminate Mr. Lee” in the Jones murders.

That’s complete nonsense, said Dowdy, who arrested Larry Lee for Moore’s murder and was present the entire trip back to Georgia. That never happened.

Johnson also wrote that there was physical evidence that Larry Lee was involved – the shotgun Bruce Lee sold – a weapon that was not stolen from the Jones family, which prosecutors knew at the 1987 trial, and Johnson would have known if she reviewed the case as she claimed. Johnson also pointed to the “Trust Company” bank bag Sherry Lee saw Larry Lee with. But the former DA told the Jones daughter to lie and say there was a Trust Company bank bag. It was actually a First National bank bag, she told the police at the time of the killings, facts Johnson would also know if she read the habeas judge’s opinion.

No effort was made to investigate the Yarbrough brothers, either in the 1980s or in 2015 when the case against Larry Lee was so reluctantly dropped by the district attorney.

Although The Press couldn’t locate Joe Yarbrough through public records or a background check, Robert Yarbrough was paroled Oct. 31, 2011. Both Yarbroughs were sentenced in 1990 to life in prison for the murder of the store clerk Glenda Ann Strickland.

Larry Lee is still in prison, serving the life sentence for Moore’s murder. Although there was no evidence Larry Lee shot anyone or even had a gun during the burglary of Moore’s home, he took part in a burglary during which his brother shot Moore to death. In Georgia, that made him a party to the crime and guilty of murder.

Lee pleaded guilty to murder in Moore’s case in 1988. If it hadn’t been for the decades on death row for the Jones family murder, Lee would have been eligible for parole after serving seven years.

Sandy Hodson is a staff reporter covering courts for The Augusta Press. Reach her at sandy@theaugustapress.com.