Editor’s Note: Sandy Hodson’s 14-part investigation into how justice is administered in the Brunswick Judicial District continues today with Part 6. This story looks into the mishandling of the Brunswick Judicial District murder trials of the two men accused of murdering Lavelle Lynn and Robert VanAllen. Earlier installments of the series can be found elsewhere in The Augusta Press website. Series stories will be published on Sundays and Thursdays.

Two years after Dennis Perry began serving his back-to-back life sentences, veteran death penalty trial attorney Mike Mears prepared to defend Buddy Woodall on capital murder charges in Glynn County.

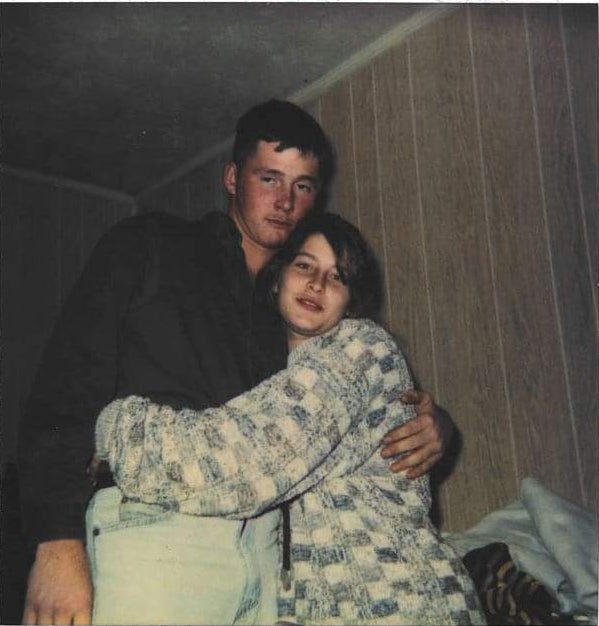

Mears never believed Woodall killed his uncle Lavelle Lynn or Robert VanAllen on Labor Day 2000. Woodall and his brother-in-law David Wimberly were both charged in the case and each faced separate death penalty trials. Woodall was to go to trial first.

Golden Isles Injustice

Part 6

Mears tried to get the trial moved out of Glynn County where the double homicide took place on a lonely county road on the far west side of the county. Although the victims, Lynn and VanAllen; the accused, Buddy Woodall and his brother-in-law David Wimberly; and several witnesses were all from Brantley County, Mears worried that it would be impossible to seat an impartial jury. He contended too many in Glynn County would know Lynn’s brothers, one of whom was a county commissioner and a second who sat on the school board. But Judge Stephen Scarlett denied the motion for a change of venue.

On the eve of Woodall’s trial in 2005, Mears was working at his Atlanta office when he became ill and was rushed to the hospital. He had suffered a stroke and was unable to continue working on Woodall’s defense.

Woodall’s new attorney, Chris Adams, had four months to prepare for trial. Woodall said he and Adams clashed from the beginning. In his opinion, Adams totally focused on the penalty phase of the trial. He was insistent Woodall should take a plea, and although Woodall told the judge he wanted to fire Adams, Scarlett wouldn’t allow it. Then and now Woodall insists he’s innocent.

Before the trial began, the defense had won an argument that the jury shouldn’t be told that the suspected murder weapon was stolen during a burglary at the home of Woodall’s parents. But during the trial, Scarlett changed his mind after Arnold “Chip” Pine testified he had seen Buddy Woodall with a pearl handle handgun, like the .25 caliber Lorcin taken during the May 8, 2000, burglary.

Jeffrey “J.R.” Wimberly insisted that he only made an incriminating statement against his brother and Woodall – that the two asked him the day before the killings to help rob Woodall’s uncle – because Lt. Scott Trautz threatened to see to it that his probation was revoked, and he would go to prison. He recanted the statement at Woodall’s trial.

Wimberly said he was coerced into making that statement, and he denied telling an acquaintance, Allen Mercer, that his brother and Woodall asked him to participate in the robbery. Mercer corroborated Wimberly’s claim he didn’t tell him anything.

GCPD Lt. Tom Tindale testified Mercer told him J.R. Wimberly implicated his brother and Woodall in the murders.

An FBI forensic examiner testified that three of the tires on Woodall’s Pontiac could have made the tire tracks found at the scene of the murders. GCPD officers testified that the track width of the Pontiac was the same as the vehicle that left the prints.

But Woodall’s blue four-door 1987 Pontiac has a track width of 57 to 59 inches. The light blue or white 1985 Honda Accord Hatchback the witness described seeing at the murder scene has a track width of 56 to 57 inches, according to car manufacturers’ dimensions. At trial, no one talked about the Honda Accord Hatchback, however.

Adams complained during the trial that the prosecutors dumped 1,300 pages of discovery on the defense right before trial, violating the rules of discovery and making it impossible to assimilate the information.

The father and son who rode their ATVs passed the murder scene and saw two men there did not identified Woodall or David Wimberly from photo lineups. The judge, however, let the man’s son testified that he picked out a man who look like Woodall as possibly being one of the suspected killers.

Much of the trial centered on the security video from the Paige’s convenience store on Post Road, not far from Bladen Road where Lynn and VanAllen were shot to death. Woodall was on the video. He had stopped to use the bathroom. It was just before 10 a.m., the same time a pay phone in front of the store was used to call Lynn’s home.

Police and prosecutors believed the call was the one that lured Lynn and VanAllen to the railroad crossing over Bladen Road. But the call from an alleged stranded motorist, who everyone agreed Lynn must have known, came in earlier that morning. By 10 a.m., Lynn and VanAllen had already left in the tow truck.

On Sept. 10, 2005, Woodall was convicted of murder and faced a possible death sentence.

As he had before trial, the prosecutor offered to take the possibility of a death sentence off the table. This time he only asked that Woodall answer questions about Wimberly’s involvement in the murders. He refused.

The jury rejected both the death penalty and a sentence of life in prison without parole for Woodall. Instead, they imposed the most lenient sentence possible: life in prison with the possibility of parole.

Nine days later, then Assistant District Attorney Keith Higgins dismissed the capital murder charges against David Wimberly.

In the motion to dismiss Wimberly’s case, Higgins wrote that while there was a strong circumstantial case against Wimberly, it might not rise to the level required in Georgia – that the evidence would “exclude every other reasonable hypothesis except the defendant’s guilt.”

Higgins complained in the motion that Wimberly’s defense attorney knew it was a circumstantial case, and he was trying to take advantage of the prosecution by pushing for trial. Wimberly’s attorney was trying to “orchestrate” an acquittal, and he continued to “orchestrate an acquittal of his client by asking the court to enter an order that would require the state to try David Wimberly under the current evidentiary circumstances,” Higgins wrote on Sept. 19, 2005.

Wimberly had been in jail for four years at that point. He was released when the case was dropped.

Although Wimberly had never lived outside of Brantley County, he moved to Kentucky after that. Woodall is still serving life in prison.

Sandy Hodson is a staff reporter covering courts for The Augusta Press. Reach her at sandy@theaugustapress.com.