Editor’s note: With this installment, Sandy Hodson’s 14-part investigation into corruption in the Brunswick Judicial District concludes. In this story, Sandy asks attorneys, the sitting district attorney and others who are familiar with how the judicial district functions to assess what has happened there and to consider what might be done to correct the problems there.

Golden Isles Injustice

Part 14

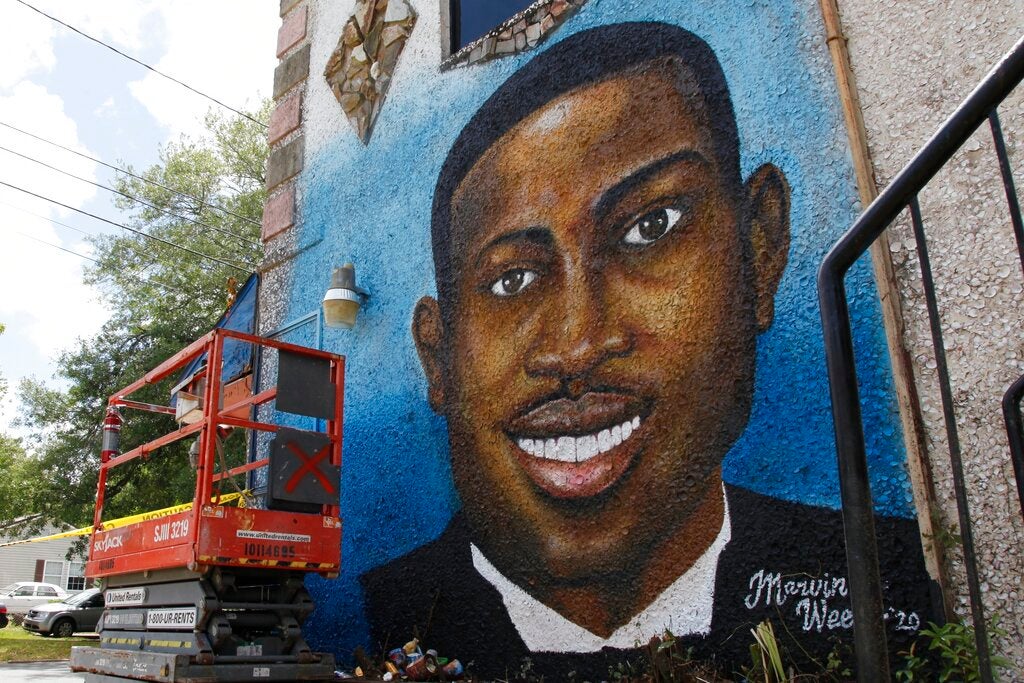

The derailed plan to portray Ahmaud Arbery as the bad guy when three men trapped him and murdered him on a residential street one Sunday afternoon in February 2020 was just the tip of the iceberg when it comes to corruption in the Brunswick Judicial Circuit, said veteran attorney Newell Hamilton.

“When you can’t see right from wrong or just don’t care, corruption flourishes,” he said. Brunswick is his hometown. Little things – like someone’s child getting a break or going to bat for a friend of a friend – can be overlooked. But when he took over the defense of Guy Heinze Jr. who was facing a death penalty if convicted of murder in the brutal deaths of eight people, that was the end for him.

When it started in the seemingly quiet little corner of southeast Georgia may never be known, but corruption was churning along swimmingly as far back as the late 1980s when Larry Lee was arrested, convicted and sentenced to death for the murders of Clifford and Nina Jones and their teenage son Jerold.

“It is appalling to this court that a trial judge in this state would refer to a new trial being granted on ‘a technicality,’ a layperson’s term for such things as constitutional rights. No wonder the prosecution team felt they could get their way with almost anything in the trial of (Lee),” Judge Gary Clinton McCorvey wrote in a footnote to his 145-page opinion reversing Lee’s conviction.

Lee is one of two men convicted of heinous killings in the Brunswick Judicial Circuit who are listed in the National Registry of Exonerations.

There have been questions about the Brunswick circuit and the district attorney’s office, the bare knuckles tactics used, said Ken Otterbourg of the National Registry of Exonerations. They’ve seen clusters of multiple wrongful convictions around the country, but it’s been in big cities, not rural areas like the Brunswick circuit with a five-county combined population that only adds up to the population of Richmond County.

The problem with wrongful convictions is it takes a massive effort to prove the defendant is really innocent, Otterbourg said. It’s very hard to undo a wrongful conviction.

“There are a lot of bad convictions that need to be looked at,” he said.

It can take millions of dollars and hundreds of hours of legal work to overturn convictions as happened in the Dennis Perry case. Perry was convicted of killing a husband and wife inside a church. Decades can pass before some wrongdoing is discovered – like evidence being withheld from the defense about a witness paid a reward and the loss of evidence, as in Perry’s case.

Buddy Woodall has spent 21 years in prison for the killings of his uncle Lavelle Lynn and his friend and coworker Robert VanAllen in Glynn County. He has always maintained his innocence. This year, the Georgia Innocence Project has taken up his case.

“This is hard not being guilty of something and being in this place. It is really hard,” Woodall said. He is serving a life sentence in prison. He tried to get his wife, Kristy, to divorce him and tell their three boys that he died after his conviction.

“Like he was going to get rid of me that easy,” Kristy Woodall said of her husband’s request.

Buddy Woodall said he wouldn’t have made it this far without her and their sons’ support, but it’s still hard to go day after day, year after year in prison.

“It’s really not easy, and as time goes by it gets harder and harder, and the window for opportunity gets smaller and smaller,” he said.

Brunswick Judicial Circuit District Attorney Keith Higgins prosecuted Buddy Woodall and still believes in his guilt. But if the case came back, he said he would assign it to another prosecutor in his office.

Higgins, who dismissed the case against Perry last year after winning the race for district attorney against incumbent Jackie Johnson, told The Augusta Press this summer that while he doesn’t consider himself a reformer, he has pledged to do what’s right in every case regardless of anyone’s influence. Since he took office, he has dismissed charges in two other pending murder cases, one a triple homicide.

If any case comes back on appeal, Higgins said he will look at the evidence in the case and any alleged misconduct.

“I don’t believe technicalities should stand in the way of doing what’s right,” Higgins said.

But Higgins refused to discuss any case that was prosecuted before he became the district attorney.

John Wetzler had a client in one of those cases Higgins didn’t want to discuss. Donald Dale was arrested along with David and Peggy Edenfield and their son, George in the May 2007 rape and murder of 6-year-old Christopher Barrios. The Glynn County Police Department knew from the beginning Dale was innocent, but they and the prosecutors continued to push for his conviction on murder and other charges, Wetzler said.

“Everywhere you go there’s some corruption,” Wetzler said. “But (the Brunswick Judicial Circuit) is one of the most corrupt places I’ve ever been in my life.”

Wetzler considers that fact he was never in the inner circle of power a good thing.

“I walked away with clean hands,” he said.

He couldn’t believe it when Greg McMichael, who he had worked with when he was an assistant prosecutor, his son Travis and neighbor Roddy Bryan weren’t charged with Arbery’s murder for months. He was quoted in The Daily Beast as being critical of the decision, he said. Wetzler said he got a threatening phone call afterward.

“(Jackie Johnson) She thought she could get away with it,” he said.

Johnson and the police pointed fingers at each other, and Johnson has since been indicted for her actions in the Arbery case. Both arguably tried to bury the case. When the GBI took over the case and interviewed Glynn County police, most of the officers initially involved in Arbery’s slaying said they still believed it was a justified killing, and Johnson and Greg McMichael repeatedly talked to each other after Arbery was killed, according to their phone records.

Johnson lost her bid for reelection after Arbery’s murder, and a new police chief from outside Glynn County was hired. But many of the officers involved in Arbery’s initial investigation, like Stephanie Oliver, who was in charge of the GCPD investigation of Arbery’s death – and whose inaction meant that GCPD Lt. Corey Sasser wasn’t in jail and was able to kill his estranged wife and new boyfriend – are still on the force. Several, like Oliver have been promoted into leadership roles.

To be a defense attorney in Brunswick is nearly impossible unless you played by the rules set by the powers that be, Wetzler said.

“If they are trying to make a living, you can’t afford to confront these people,” he said.

Stephen Bright, Yale Law School professor who founded the Southern Center for Human Rights, represented people charged with capital offense all over Georgia and knows that what Wetzler said about defense attorneys being hampered in their hometowns is true.

A culture develops in areas where no one is watching and no one is being held accountable, Bright said. Judges should hold prosecutors responsible, but they do not, he said. If you don’t have a defense bar raising objections when warranted and media reporting on misconduct, it just continues to build, he said.

Bright said because he came from outside the area where many cases he defended were, he was able to bring out issues that could ruffle the feathers in judicial circuits.

“Cases are often reversed for prosecutorial misconduct, and DA calls a press conference to criticize the judge’s reversal when it was the DA’s fault,” Bright said.

He convinced the U.S. Supreme Court to grant Tony Amadeo a new trial in Putnam County because the prosecutor improperly used his influence to limit the number of Black potential jurors. Bright said when the case was returned to Putnam County, the judge appointed a local attorney within one month of the trial date. Bright had to go back to the appellate court to stay on his own case, he said.

When one side gets an unfair advantage, then the scales tip over and wrongful convictions can result, Bright said. And if a court can’t get the basic job of sorting the guilty from the not-guilty, how can it be trusted, he asked. There have long been questions about what’s happening in the Brunswick Judicial Circuit.

Washington, D.C.-based attorney and podcaster Susan Simpson, who has now investigated several Georgia cases, and who’s work helped at least three men get successful appeals – like Dennis Perry in Brunswick Judicial Circuit – said what has happened in Brunswick Judicial Circuit isn’t normal. It happens in other places, but it’s still wrong.

In a Sept. 1, 2020, report for the National Registry of Exonerations, a team looked at the 2,400 exonerations in the United States from 1989 to February 2019. They found that government misconduct, by police and prosecutors, accounted for 54 percent of the wrongful convictions. By exoneration, the study meant that someone convicted of a crime is officially and completely cleared based on new evidence.

“We conclude that the main causes are pervasive practices that permit or reward bad behavior, lack of resources to conduct high quality investigations and prosecutions, and ineffective leadership by those in

command,” the study begins.

There are bad actors in any profession, but in the justice system, they must be rooted out, and that is why judges must, not may but must, report any judge or lawyer who has exhibited dishonesty, untrustworthiness or professional unfitness, said attorney Robert Ingram, a former president of the State Bar of Georgia. Ingram has also served as the chairman of the Judicial Qualifications Commission, the judicial disciplinary board, and he has served on the bar’s disciplinary investigative and review committees.

The rules of professional conduct mandate judges report misconduct, but it isn’t anything judges or lawyers want to do, Ingram said.

“We know it’s human nature … judges are reluctant to get involved,” he said.

But the rules of conduct must be maintained to keep people’s trust in the system, Ingram said. “You need people to believe in the system for it to work. It’s really unfortunate when you have prosecutors who ignore the rules when their job is to enforce rules.” Prosecutors must be accountable, too, he said.

If people lose faith in the judicial system, “Then we’re like a third world country where everybody knows there is no justice,” Ingram said.

Sandy Hodson is a staff reporter covering courts for The Augusta Press. Reach her at sandy@theaugustapress.com.