Editor’s Note: Sandy Hodson’s 14-part investigation into how justice is administered in the Brunswick Judicial District continues today with Part 2. The story picks up 20 years after Larry Lee was wrongfully convicted in a Brunswick Judicial District court of the 1986 murders of three members of the Jones family in Wayne County. Lee’s story, the subject of Part 1, can be found elsewhere in The Augusta Press website. Series stories will be published on Sundays and Thursdays.

MORE: Glynn County justice issues go back decades before Arbery case

The misdeeds committed by Brunswick Judicial District legal authorities in Larry Lee’s 1986 murder prosecution for the Jones family slayings were mirrored in a case that moved through the courts two decades later, that of Dennis Perry. Different county, different investigators and different prosecutors, with the exception of John B. Johnson. But same judicial circuit: Brunswick.

Johnson’s boss, now Judge Stephen Kelley, was so impressed with the results of his work in Perry’s case that he nominated Johnson for assistant district attorney of year. Johnson won.

Perry was accused in the killings of Harold and Thelma Swain, ages 66 and 62, at the Rising Daughter Baptist Church in Camden County on March 11, 1985. The couple had no enemies, and no one could think of any reason someone would want to kill the deacon and his wife. Their case would remain unsolved for years.

Golden Isles Injustice

Part 2

An arrest in the slayings finally occurred nearly 15 years later after Sheriff Bill Smith spent $40,000 of drug forfeiture money to hire Investigator Dale Bundy, a former deputy and friend, to solve one case, the Swains’ killings, according to a report on the case from the Georgia Innocence Project. Bundy identified Perry as a suspect within days of being hired to work the case.

Then-District Attorney Stephen Kelley filed notice of his intention to seek a death sentence if Perry was convicted of the Swains’ murders, but Perry was offered an astounding deal for someone who allegedly gunned down two people in a church. If he plead guilty, he would get a 10-year prison sentence with credit for time served and the prosecutor’s promise to request an immediate parole hearing, according to the habeas petition filed for Perry. He turned it down and went to trial.

Perry’s trial attorney didn’t know that the state’s star witness was paid $12,000 from the sheriff’s drug forfeiture funds for her testimony. That witness gave the jury Perry’s alleged motive and the means to get to the church where the Swains were killed. Perry’s attorney also didn’t know that the fire break she said Perry could have used to sneak from his grandparents’ home to the church was on property Investigator Bundy owned, according to the work of attorney Susan Simpson for the podcast Undisclosed, and the Georgia Innocence Project attorneys who took on Perry’s case.

Perry’s trial attorney, Dale Westling, also didn’t know that another witness, whom he painted at trial as the most likely person to have killed the Swains, had once confessed to the killings. That man was given immunity by the prosecution to testify at Perry’s trial, and prosecutor John B. Johnson coached him on how to answer certain potentially troublesome questions about that confession. Perry’s appellate attorneys found the email Johnson sent to the man.

What was never explained was a pair of glasses found next to the victims that didn’t belong to either of them. Perry didn’t need glasses then. And DNA from hair caught in the glasses didn’t come from Perry or the victims. Further, evidence of his alibi was missing when Perry went to trial.

The original investigators on the Swains’ murders looked at Perry in the 1980s as a possible suspect, but they cleared him. According to the Georgia Innocence project, his employer in 1985 had closed by the time of the trial, so no employment records were available to prove his alibi.

Other evidence that went missing was a tape recording of Erik Sparre in which an ex-wife said Sparre incriminated himself in the Swains’ murders. Atlanta Journal and Constitution reporter Joshua Sharpe proved Sparre’s alibi for the 1985 killings was faked. An investigator with the Georgia Innocence Project obtained a DNA sample from Sparre’s mother that linked Sparre to the hairs found in the eyeglasses left behind by the Swains’ killer.

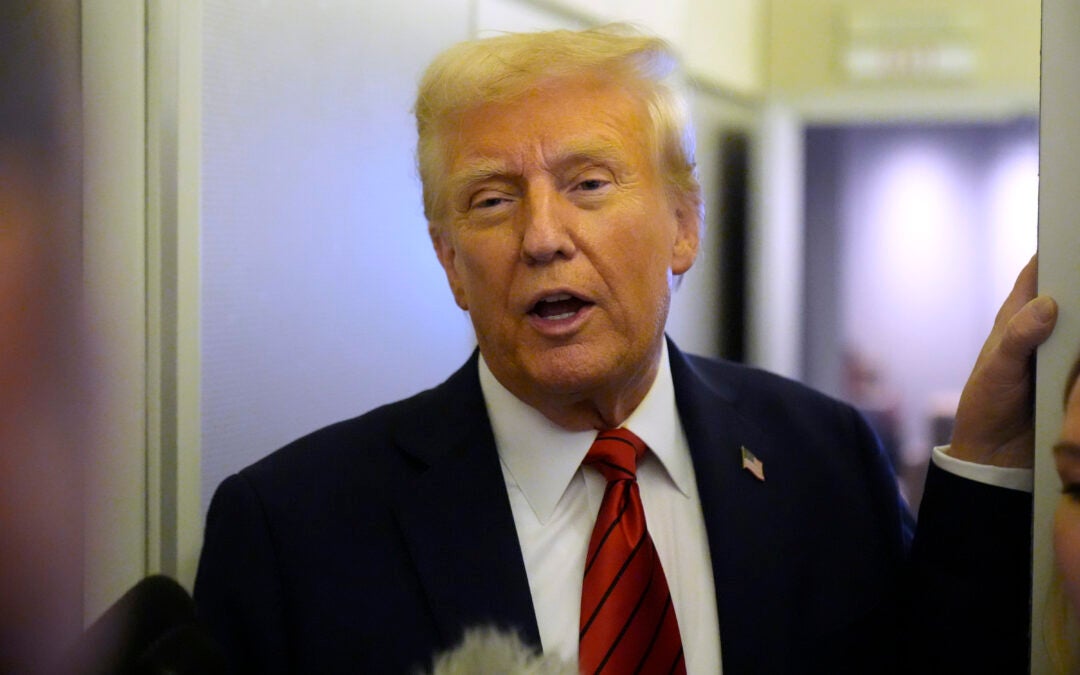

Faced with the evidence of misconduct in the case, the DNA evidence, and Sparre’s phony alibi, District Attorney Jackie Johnson and her staff continued to argue that Perry wasn’t entitled to a new trial. The prosecutors insisted Perry waived his right to appeal after the jury found him guilty in an agreement that took the death penalty off the table. In Georgia, death penalty trials have two parts: the guilt/innocence phase and the sentencing phase. Perry agreed to a life sentence, and the second phase of the trial wasn’t conducted.

But Judge Stephen Scarlett overturned Perry’s conviction for the Swains’ killings in July 2020 based on the DNA findings. District Attorney Jackie Johnson didn’t drop the case against Perry, however. She said she was waiting for the renewed GBI investigation to be completed.

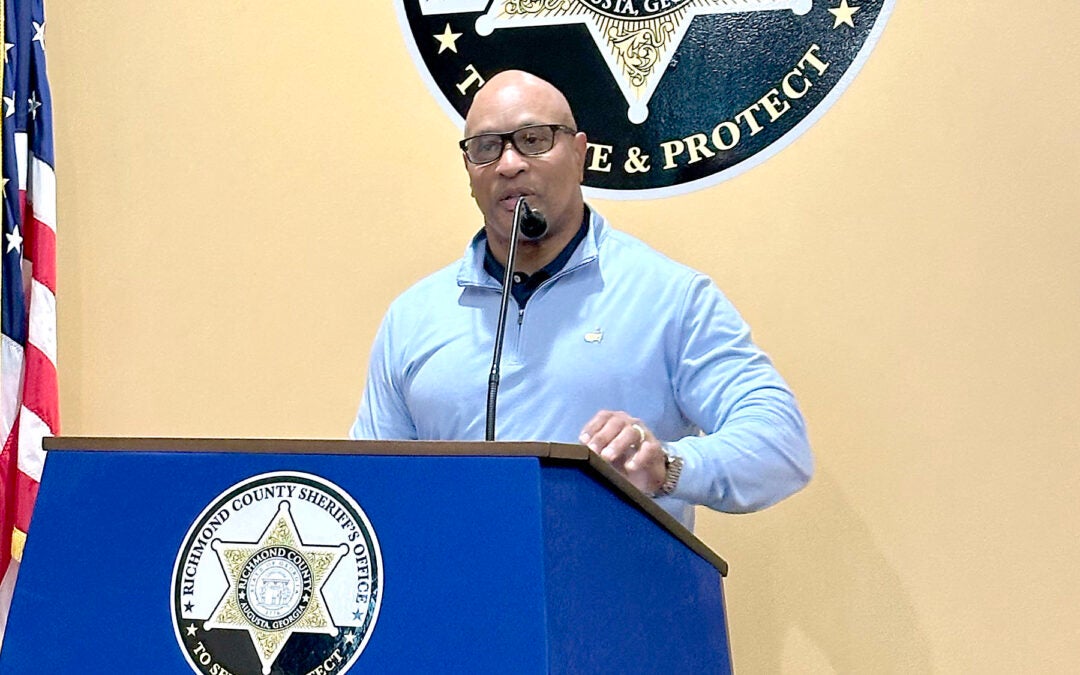

Nine months after the murder of Ahmaud Abrery, District Attorney Johnson lost the November 2020 election to Keith Higgins. Both had worked in the district attorney’s office until the governor appointed Johnson to fulfill Kelley’s term after the governor chose him to be a superior court judge. Higgins was fired, as was another assistant prosecutor, after Johnson took over.

In 2021, Higgins, as new district attorney, formally dropped the criminal charges against Perry. On May 2, 2022, Gov. Brian Kemp signed the bill passed by the Georgia General Assembly to give Perry $1.2 million in compensation.

Perry spent 20 years in prison for crimes he didn’t commit.

In July, Higgins told The Augusta Press that his office is still working on the Swains’ murder case.

Sandy Hodson is a staff reporter covering courts for The Augusta Press. Reach her at sandy@theaugustapress.com.