Usually most people (including a number of my students) don’t pay much attention to history, but in the last couple of years history has become at least a warmer topic.

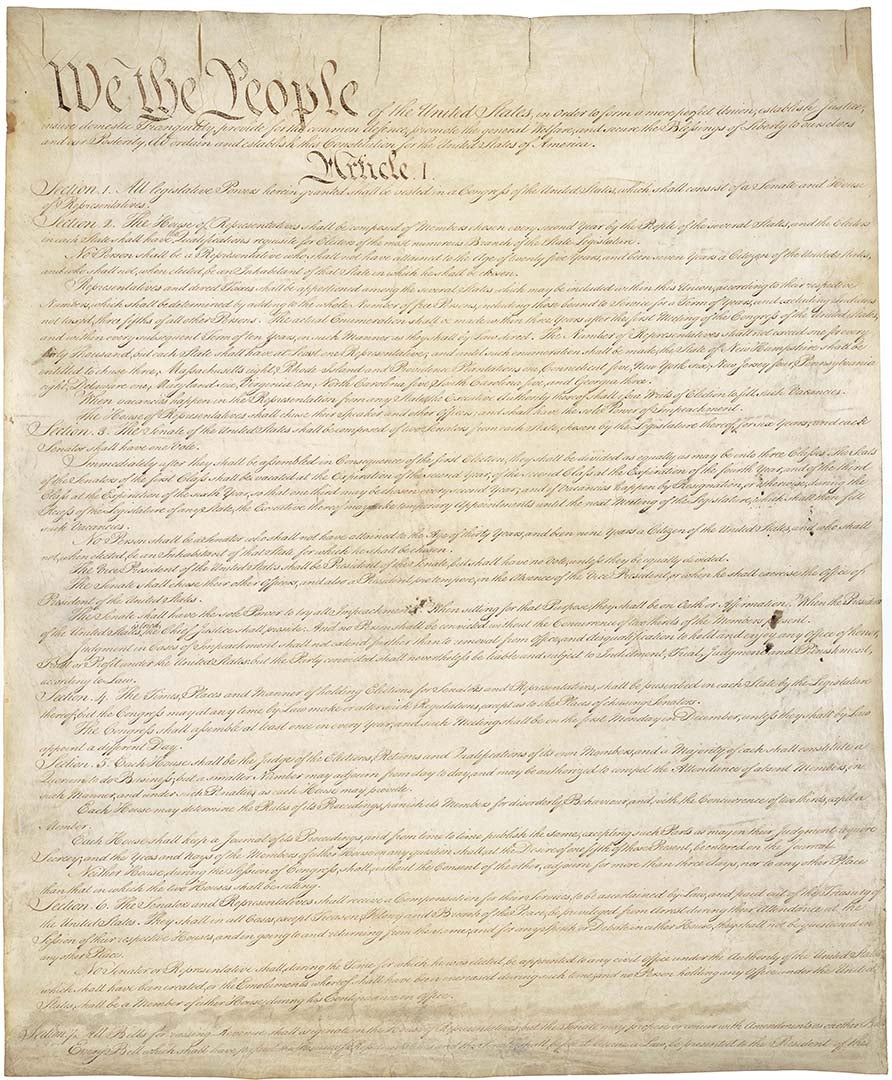

First, the “1619 Project,” triggered responses such as the “1620 Project” and the “1776 Commission,” the latter a short-lived effort that emerged from the preceding presidential administration. The recent events at the Capitol led to an upsurge of discussion about the Constitution, which is inseparable from American history. The latter is most important, especially as there has been some contradictory behavior in the responses.

[adrotate banner=”30″]

Personally, having been a historian for nearly 35 years, I thought all this would be a good thing. Maybe some good history books would get read. Or history requirements might be strengthened rather than weakened, as the University System of Georgia recently tried to do in the state’s core curriculum for colleges and universities.

The appalling lack of knowledge about our basic history, our Constitution, the Declaration of Independence, etc., is a major headache, and I can tell you – it’s gotten worse.

No Child Left Behind was one of the things that has caused this, but it’s not the only thing. My incoming freshmen used to have a basic grasp of our Civil War, even if occasionally some of their ideas were a bit off the beam.

That may be generational, of course; my earlier students had grandparents who cared deeply about that war and may have told family stories. But when it comes to the Constitution, everyone who comes out of high school should know the history and content of the Constitution. Especially as e-v-e-r-y-b-o-d-y blithely talks about their rights, and even their constitutional rights, without ever having read the document.

No big surprise. History is not the only thing that has suffered in teaching. Both history and civics in many schools were for years taught “on the side” by the athletic department, acceptable if Coach has a full college background in history or political science.

But let’s not beat up on the kids. Adults often are no better, and it is not as if good books or even the documents themselves are hard to find. The bigger problem, of course, is that except in crises, the Constitution does not get the public attention it deserves. It is more or less taken for granted. And the problem does not lie with the public alone.

Responding to public concerns, the New York Times Magazine launched the 1619 Project, whose purpose is to treat the beginning of slavery as this country’s birth, effectively making slavery the central narrative in all of American history. Unsurprisingly, the contents of the project, including the school curriculum, is not an attempt to tell the story of slavery. Instead, it is heavily ideological and centers the whole history of the country around slavery. A dozen distinguished scholars noticed the fundamental flaws and wrote the editor of the NYT Magazine, who refused to make any corrections. And initially refused to publish the exchange of letters.

Predictably, there have been attempts to correct this. The White House launched the 1776 Commission; the National Association of Scholars has developed the 1620 Project, which may yet gain some traction. However, the editor of the American Historical Association’s journal thought the reorientation of the country’s origins to 1619 was “laudable.” He notes quite correctly that teaching about slavery and the Black experience is already a major part of history courses (which makes the 1619 Project’s claim to finally be telling the truth rather untruthful). Yet he rejects the substantive criticisms of the 1619 project as being matters of interpretation and opinion. I do have to give him credit for pointing out that the harshest criticism of the project came, from all people – Marxists!

[adrotate banner=”22″]

However, what all this misses is that there can be subtle and insidious effects by changing the focus on how we understand the country. Let’s go back all the way to the Great Depression. Between 1929 and 1932, industrial production in both the United States and Germany fell by 47 percent, and unemployment soared to over 25 percent. In Germany, the result was the collapse of the democratic republic, the sweeping away of its constitution, and the power seizure of Adolf Hitler and the Nazi party.

In the United States, all that happened was that the Democrats swept the 1932 elections, and a Democrat was elected president (four times!). The Constitution was only changed in one way; Prohibition was repealed. Why did we come through this period of unprecedented economic crisis and an unprecedented war, without modifying or ditching the Constitution?

Because Americans collectively had a great reverence for the Constitution, seeing it as both our national creation, and our national foundation. Germans had no such feelings toward theirs.

This is not inevitable. On Jan. 6, a mob stormed the U.S. Capitol, many of its members bearing American flags and convinced in their hearts that they were being totally patriotic. Yet, a few decades ago, this would have been unthinkable. What was disrupted on Jan. 6 was not a building. Rather, it was a Constitutional process. Congress was Constitutionally certifying the Constitutionally submitted Constitutional electoral votes.

Fortunately, the vast majority of the pro-Trump demonstrators did not participate in the storming. Otherwise, the results might have been worse. But both disrupting a Constitutional process, and demanding that Congress do something un-Constitutional, was unprecedented. Yes, Congress has been stormed before, but that was in 1785, before we had the Constitution.

But that’s not the biggest problem. How we teach about the Constitution can affect how it is viewed. I am not suggesting for a moment that we order children to swear that they revere Constitution. Nor am I suggesting that the Founding Fathers should be treated as saints. But we should keep a focus on the fact that this document was a remarkable achievement and that its authors were remarkable men.

If, for example, we focus on slavery and its consequences as the fundamental historical foundation of our country, we will soon start focusing on the fact that many of the Founding Fathers were slaveowners. In other words, we treat them not only as ordinary but also as evil, and then we start treating the document purely relativistically, as the output of a bunch of slaveowners and lawyers who wanted to protect their interests. Their thinking, their philosophy, their debates, etc., will all be swept aside. This is what the San Francisco school board did with its mass renaming nonsense, even erasing President James Abram Garfield, assassinated after only six months in office.

And if we start thinking that way about our national foundation, the Constitution, how long can it survive? I think most of my fellow historians were as outraged by the events at the Capitol as I was. But it makes no sense to denounce Trump and his more extreme supporters for showing no respect for the Constitution while at the same time helping erode its image on the other.

I am not suggesting that what happened in Germany in 1933 will happen here. But I am not going to say that it can’t.

Hubert van Tuyll is an occasional contributor of news analysis for The Augusta Press. Reach him at hvantuyl@augusta.edu

[adrotate banner=”20″]