Since 2017, Augusta has funded its My Brother’s Keeper program to the tune of nearly $40,000 annually, but the mayor’s office has declined to account for how much of that money has been spent.

The mayor’s office has also declined to provide most invoices and receipts for expenditures from the account. A request for that information netted about a quarter of the expected invoices and an explanation from Mayor Hardie Davis’ Chief of Staff Petula Burks was that other invoices did not exist or that they would be difficult to dig out.

More: Augusta Commissioners Ready to Travel Again

More: Tax Commissioner Steven Kendrick To Run For Mayor

My Brother’s Keeper was created by the Obama administration in 2014 to provide greater opportunities to succeed for young men of color. It is now run as the My Brother’s Keeper Alliance administered through the Obama Foundation, according to the foundation’s website.

Augusta has had an MBK organization since 2017, and it is run out of Mayor Hardie Davis’ office, which also has oversight on the city-funded budget for the program.

In fiscal year of 2020, the city spent $34,177.02 in general fund revenues on the at-risk program for young men of color. Those expenditures covered items such as education and training in the amount of $7,291.30; special events in the amount of $3,863; program supplies in the amount of $4,527.43; and computer software supplies in the amount of $4,037.18.

Davis’ office spent more than $4,000 on digital design, websites and computer consulting from the MBK account. Another $9,000 was spent on “management consultants”.

More: Mayor Davis Opposes Six Senate Bills; Commission Passes Resolution

More: Response to the Mayor’s Task Force on Confederate Monuments

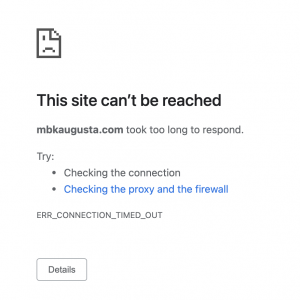

MediumFour, LLC, a Ft. Lauderdale, Fla., web design/marketing company, received $5,000 from the MBK account for a website that does not work. A spokesman for MediumFour refused to detail the work they provided for the city and referred inquiries to the mayor’s assistant Petula Burks, who is from the Ft. Lauderdale area. Ms. Burks moved to Augusta in September 2020.

MBK does have a page on the Augusta.gov main site, but it does not really show anything about the group’s activities. A Facebook page lists My Brother’s Keeper Augusta as a “government organization,” but there have only been two posts on the page made in January this year, both of which deal with the mayor’s program, “Covid Conversations.” All other posts date back to 2019.

Burks said she did not know what the $5,000 was spent for with MediumFour and added that she would have to look into the charges before she could give details. The funds were spent three months after she was hired.

The $5,000 paid to MediumFour as “management consultants” was not the only web design promotional funds spent from the MBK fund. Another $4,000 spent on web design and consulting included $2,000 paid to local photography vendor, RedWolf. Rhian Swain, owner of RedWolf, says that while she has taken quite a few photos for the mayor’s office, she has never been asked to photograph a MBK event.

Another charge on the account was $522.50 to Yolanda Rouse – Stroll the Polls. The only Yolanda Rouse who appeared in an Internet search is an Augusta photographer. Stroll to the Polls was a movement among African-American sororities in Atlanta to encourage participation in the 2020 presidential election, according to an Oct. 9 article in the Atlanta Journal-Constitution. Strolling is a tradition among African-American Greek organization in which members use the same dance or walking movements.

The MBK account also paid money to the U.S. Conference of Mayors. The mayor’s office has provided no evidence that shows how money spent on the conference or Stroll to the Polls supported the mission of MBK to help underprivileged youth, despite requests from The Augusta Press for such information.

Over $8,000 in additional charges to the MBK account went to pay credit card charges. Amounts are listed in the city budget report, but no explanation is given for what the funds were spent on.

The national MBK organization no longer provides any type of funding for local MBK organizations. Instead, national MBK helps local groups apply for grants to fund their MBK programs, according to national organization Communications Director Courtney Williams.

“We refer to these (grant applicants) as our Impact and Seed Communities. Grants, which range from $50,000 to $500,000, support programs and policies that reduce youth violence, provide second chances and grow effective mentorship programs,” Williams says.

Funding for local MBK organizations does not come from the national organization, according to Williams.

All of the funding for the Augusta MBK account comes from the city’s general fund, meaning the mayor has a separate allocation in the city budget over and above his regular budget to spend on the city’s MBK, according to Donna Williams, Augusta’s finance director.

Other cities with My Brother’s Keeper programs offer a wide variety of programs to engage at-risk young men and boys. Here is a link to what was provided for a listing of what events the local MBK has engaged in or has planned.

Daniel Fairley, the youth opportunity coordinator for the city of Charlottesville, Va., and head of the Charlottesville Alliance for Black Male Achievement, says the program continues to benefit his city with programs ranging from child literacy to college and workforce planning.

“In 2018 and 2019, I partnered with the Community Attention Youth Internship Program, Filmmaker Clarence Green and Light House Studio to provide paid summer internships to 13 young black men in our community and create two documentaries focused on the Black male experience in Charlottesville,” Fairley said.

During the pandemic, Fairley said he created a podcast that brings in experts to discuss mental health.

Other participating cities, such as Baton Rouge, La., report similar results.

The Augusta Press analysis of the financial records only included the 2020 financials for My Brother’s Keeper.

Sylvia Cooper and Scott Hudson both contributed to this article and can be reached at sylvia@theaugustapress.com and scott@theaugustapress.com.