In today’s world where cars virtually all look alike, it may be difficult to imagine that the automobile was once almost considered a, albeit temporary, member of the family. While we rarely think of our car at all unless the check engine light comes on, once cars were doted on, dressed up for parades and almost considered an extension of the owner’s personality.

Indeed, we think more of how many times we have to empty our wallet to fill the tank, than the last time we washed our automobile. To me, that is a shame.

According to Bill Kirby, of The Augusta Chronicle, the first time an automobile was shown in the city of Augusta was in September 1899. Kirby wrote that the steam-powered car was lauded as a “sensation.”

However, that really wasn’t the case around the nation as most cars of the time were powered by internal combustion engines and not steam as was the “locomotor” that Kirky described as being shown in Augusta.

Even in Europe, where Carl Benz invented the gas powered automobile, it was not considered practical as the narrow roads barely allowed for a horse and buggy.

With its wide open spaces, Americans were quicker to embrace the horseless carriage, but it took a while. Cars of the time were loud, rarely enclosed from the elements, took a strong man or an Amazon woman to crank and belched out black, noxious fumes.

Many times, cars of that period were driven with goggles to protect the eyes from flying mud and other projectiles.

Some people of the time wondered who in their right mind would want to travel under the power of 12 horses and go that fast. Keep in mind that roads were not paved and driving anywhere by horse or motorcar was not exactly a pleasant affair.

Of course, Henry Ford brought the automobile to the mainstream, but he almost torpedoed his own success. Ford was a practical man and an engineer, so he went about creating a utilitarian machine that was easy to work on, had interchangeable parts and, most importantly, reliably took folks from point A to point B and back.

Ford thought that once a man bought a Model T Ford, he would never need to buy another car in his lifetime. Thankfully, Ford’s son Edsel, saw the folly in his father’s thought process and talked him into upgrading to his vision of a new Ford product: the Model A.

Not long after, car builders would add automatic starters, tinker with engine designs to produce more horsepower and develop chassis that would not hog and bounce all over the road. They also invented the seat belt, but that didn’t take off for some reason.

Alfred P. Sloan, CEO of General Motors would take things even further. His plan was to incorporate “planned obsolescence.” Design cues as well as new technology like headlight dimmers, yearly body changes and enhancements, extravagant color schemes and finely crafted interiors became as important as the power plant that drove the car.

The Great Depression, followed by World War II, would hamper the car industry, but with the advent of the interstate highway and a booming post-war economy, the automobile became an American cultural icon.

It was during the 1950s that planned obsolescence really took over. Manufacturers laid on chrome and created tail fins that they hilariously called “stabilizers,” and every new year model was touted as the next year into the future.

Every new car feature had its own name and car transmissions were the best when categorizing their names: Hydromatic, Dynaflow, Powerglide. Manufacturers created the electric eye automatic headlight dimmer, push button transmissions and even a spare tire that acted as a fifth wheel and aided in parallel parking.

While technically obsolete, used cars from the 1930ss and 1940s were snapped up by teenagers who would soup up the engines and convert them into barely legal street racers.

Car companies created sports cars, personal luxury cars, muscle cars and high-end land yachts featuring the lower, leaner body designs or as Chrysler’s Harley Earl would say, “the forward look.”

“Suddenly! It’s 1960!” advertisements blared.

Manufacturers competed to fill virtually every niche and taste while attempting to craft brand loyalty. Chrysler, General Motors and Ford attempted to create classes or “fields” of cars within and between the various marques they owned.

A General Motors’ fan might start out with a low-priced Chevrolet Belair and later trade up to a Pontiac Bonneville in hopes of one day being able to impress everyone on the block by driving a Cadillac. Rather than having to pay cash up front, for the first time, people bought on credit and trading the car after about three years of ownership became the norm.

The “Sunday drive” became a bit of a cultural thing as families would pile into their sedan to aimlessly cruise around “with no particular place to go,” as Chuck Berry would famously sing; and why not when gas was cheaper than tap water?

Drive-in theaters, drive-in church services and drive-in restaurants became common as motor lodges sprang up along the new highway system

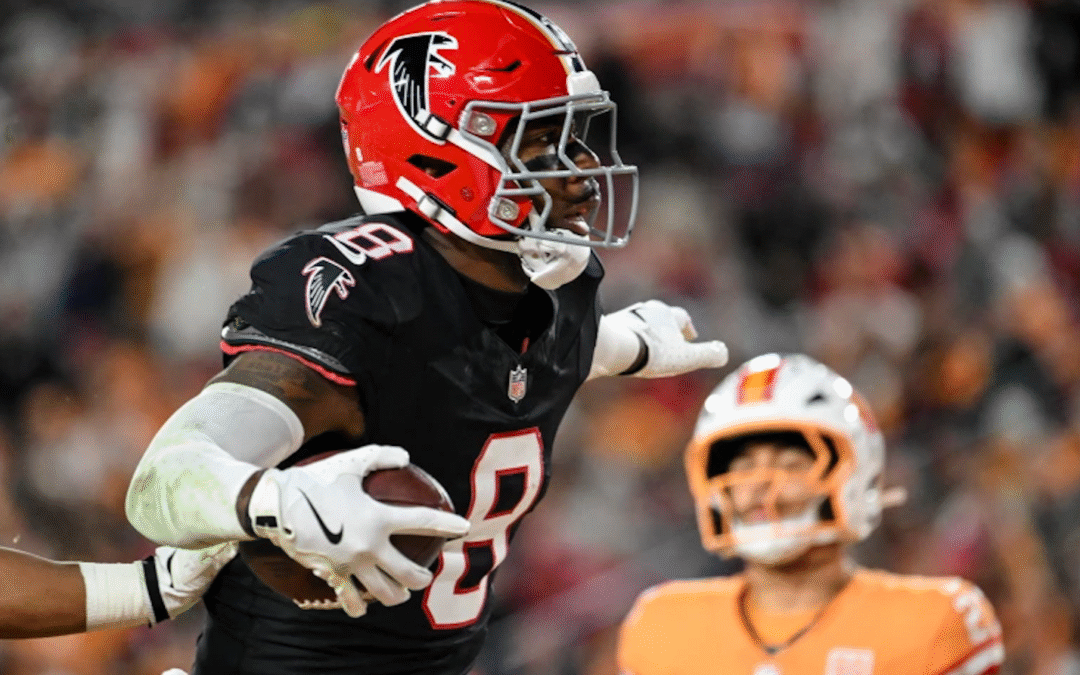

In Augusta, the hottest weekend ticket was to the Augusta International Speedway in Hephzibah. During the decade of the 1960s, the speedway was the place to be to watch all sorts of auto racing, but a major change was on the horizon and the speedway was one of the first casualties.

Automobiles suddenly got really expensive to own and maintain.

The former tried and true process of planned obsolescence and the continual introduction of new gadgets ultimately came back to bite the American car companies in the bottom line. Since most people traded for new cars within a few years, quality control took a back seat and many cars began rusting after only about a year.

In the 1970s, federal emission controls and fuel shortages due to Middle East politics put the squeeze on automakers, and they responded in the worst way.

Rather than pay attention to market demands and respond to the more and more popular Japanese and European cars, American companies went crazy on the drawing boards producing some of the most ridiculous looking cars.

Anyone over 50 can remember the American Motors Pacer, the “Glass Egg on Wheels.” Instead of properly downsizing across the board, the big three automakers offered economy cars that fell apart shortly after leaving the dealership or even exploded on impact.

What were once midsize cars backslid into the 1950’s with huge long snouts in front replacing the fins in back and most American cars grew to such a size that they almost needed to be parked in an aircraft hangar instead of a single car garage.

Automakers turned to more gimmicks instead of more quality. Silly looking paint jobs and decals adorned “muscle cars,” which could barely rally 125 horsepower. Interiors began to resemble brothels with plush seating, fake wood veneers and enough ashtrays for even the kids in the back seat.

Chrysler took the gimmicks to an almost laughable level by putting actor Ricardo Montalbán in an advertisement touting the brand’s “rich Corinthian leather,” which was a run-of-the-mill leather made by a company in New Jersey.

Never ones to learn from past mistakes, American manufacturers turned to rebadging, or producing basically the same car throughout the various marques. Before long, cars were identical except for different front and rear ends.

It would be Cadillac that would basically out-Edsel the Edsel with the introduction of the Cimarron. In 1958, Ford Motor Company lost well over a billion dollars in today’s money on the ill-conceived Edsel, but at that time the ruckus only affected Ford; Cimarron would send shock waves through the industry.

Buyers immediately noticed that Cimarron was simply a Chevrolet Cavalier in different livery, but with a massive price tag. Consumers began to realize the 1974 Mustang II Mach 2 had been just a Pinto in disguise, the Lincoln Versailles was a lip-sticked up Ford Granada and that later Chryslers were virtually all the same cars with different name plates throughout various marques.

To make matters even worse, American manufacturers then began rebranding foreign cars sold with a different badge under their own umbrella. Suddenly people didn’t know if they were really driving a Chevrolet or an Isuzu.

Cars lost their personalities and no longer were seen as an extension of the owner’s personality. In today’s world, with gas prices at an all time high, no one in their right mind would motorvate around town for the sheer fun of it.

However, in Augusta, there are many who remember the Augusta International Speedway and wish that someday it could return. Many car clubs continue to operate locally including the CSRA Road Angels and one of the myriad of reasons Augusta has attracted the national film industry is that there are plenty of period cars here available to appear in period films.

It seems, at least to me, Augusta has never lost its love affair with the car and with (especially American) car companies again focused on innovation and trying to best each other in creating the automobile of the future, that love affair might continue.

But despite all the modern gadgets that have made driving fun again, I’m not going to get into a self-driving car…at least not yet

Scott Hudson is the senior reporter for The Augusta Press. Reach him at scott@theaugustapress.com