The “keeping up with the the Jones” mentality is still alive and well as modern American consumers will camp out overnight in subarctic temperatures to be among the first to get their hands on whatever shiny new gizmo that makes its way to market.

Street cred aside, it is almost never a good idea to apply this one-upmanship principle to buying a new car.

Over the past few years, the new Bronco, Mustang Mach E and Tesla Cyber Truck have all premiered to adoring crowds, but most first-run buyers ended up feeling a bit short changed when the finished product they purchased didn’t exactly hold up to the hype.

Remember when Elon Musk proclaimed the Cyber Truck to be “bulletproof” and then accidentally shot out the truck’s side window?

There are a plethora of reasons that consumers should skip the first year of a new model’s offering.

Safety is important

Anytime an automaker comes up with a new concept, it is the overall frame and suspension that are the most crucial aspects, even if the new model is not that drastically different structurally from the version it replaces. Minor changes the size of mere millimeters at the front of the vehicle might cause strain or weakness in the rear, leading to safety compromises.

Throughout automotive history, whether it is the new concepts of the Corvair, Chevette or Corvette, engineers have looked for ways to cut down the timeline of the development process to have the vehicle showroom ready quicker. This almost always leads to corner-cutting and, on occasion, the mentality of “we’ll get to that part later” has ended in tragedy.

In the early 1970s, production development for Ford’s new Pinto was moving along just fine when the bean-counters in accounting began pressuring the engineers to move faster. Designers were already aware that the metal seams of the gas tank were uncomfortably close to the metal underpinnings of the new, government mandated “safety bumper.”

Rather than take the time to fully work out the problem, Ford decided to move forward with the issue unchecked and the result was that people were killed when their new Pintos exploded in low-speed rear end collisions.

Later, it was concluded that a reworked piece of rubber sheathing that cost about a buck-fifty per car to manufacture, fixed the problem entirely.

For decades, people argued over whether the RMS Titanic or her older sister ship, the RMS Olympic were the safer of the two luxury liners. Naturally, since the Olympic ended her service in a scrap yard instead of at the bottom of the Atlantic Ocean, “Old Reliable” should be considered the safer of the two.

On paper though, Titanic was actually the safer of the two ships. Titanic had more lifeboats than her sister and the bridge of Titanic was wider, giving lookouts a better panoramic view. Those facts, along with the double-bottom keel layout, electric watertight doors and an advanced pumping system gave the illusion that the ship was impervious to disaster.

The difference between the two vessels lay not in the equipment, but in the training of the crew and their ability to properly utilize these advancements in a crisis.

In the auto world, the much bally-hooed Ford Edsel introduced the placement of the gear selector in the middle of the steering wheel, this was considered safer since the driver didn’t have to take their eyes off the road to operate the transmission.

What Ford didn’t take into account was that people were used to the horn being placed in the same area and their “muscle memory” caused them to change gears by mistake when reaching for the horn.

Also, major safety advances such as anti-lock brakes and airbag deployment systems generally take years to refine properly and require multiple trial and error attempts to successfully work out the bugs. The 1973 Olds Toronado featured the miraculous new airbag system among its many advancements; however, no one wanted to be in the cockpit when an errant sensor caused the bags to deploy without warning.

What are the upfront costs?

Remember how long it took for the compact disc, VCR and camcorder to really become mainstream? Phillips first marketed the new CD format in 1978, yet it would take almost a decade for the new audio devices to make it into cars.

Part of the reason for this is that development costs are factored into the first couple of years of manufacturing; so, in such cases, it is only the hardcore fans that are willing to pony up extra money to hear Dire Straits rock out “Money for Nothing” in digital brilliance.

With advancements like the new “infotainment” consoles one-upping one another on car lots, many times the consumer ends up paying for amenities they did not know were there and have no clue as to how to operate them properly.

Another up-front cost that factors in and people do not consider when opening their wallet is that it is not only car geeks that get agog at a promised new concept. Thieves like to get their hands on them as well, and so, purchasing insurance for a first-run vehicle tends to cost more than the follow up versions.

The ‘break-in’ period

Most people are aware that every new vehicle requires a break-in period as moving parts stretch and mesh together. Over time, the minor squeaks and groans work themselves out as the machine parts age together.

However, the tools, dyes and metal stamping equipment used to produce the vehicle require the same type of breaking-in period from the factory. Just as body panels stamped on 10-year-old equipment don’t seem to fit perfectly and begin to sag, the same is true with a freshly minted car.

First run cars always have seams that do not look quite right and that is because the machines used to produce them are themselves brand new. Not only do the seams not always line up correctly, but other machines producing rubber gaskets and the like might not yet be calibrated to be able to produce with 100% accuracy, making the car ‘stiffer’ than is optimal.

Wait for the ‘finishing touches’

Car makers have a lot of things to consider when crafting a new offering and the final design usually changes between years one and three of a new marque. Since automakers really do not know if a car will be a hit until it hits the street, learning from past experience, the designers tend to be overly cautious and conservative in their initial designs.

Take, for example, the 1934 Chrysler Airflow which was faster, safer and more fuel-efficient than anything else produced by Detroit; yet within a year, the entire design was tossed out because the public wasn’t ready to embrace such a space age design concept.

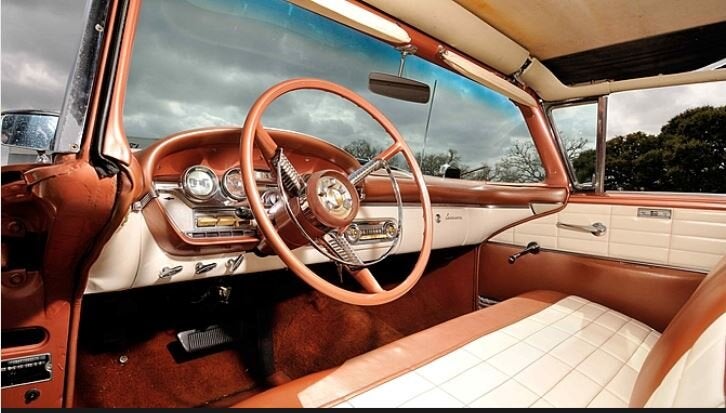

Take a look at the differences between the 1957 and 1958 Plymouth Belvedere Fury models. What you see are basically two versions of the same vehicle; but somehow, the 1957 model seems a little frumpy and looks unfinished when compared to the 1958 model whose chromed snarl became the stuff of nightmares in the 1982 movie “Christine.”

With its “forward look” design, Chrysler was not sure the public wanted dual sealed-beam headlights, or that the government would allow for them, so, one of the headlights was just a thinly disguised parking lamp. Under the grille, an ugly metal scuff pad panel jutted out of the 1957 front end as engineers continued to test exactly how much air intake the radiator needed for optimum performance.

It was the second-year offering that fully incorporated dual headlights and the classic grille design that made it onto movie posters all over the world.

See you on the road!!

Scott Hudson is the Senior Investigative Reporter and Editorial Page Editor for The Augusta Press. Reach him at scott@theaugustapress.com