(Disclaimer: The views stated in this column are those of the author and not necessarily those of The Augusta Press)

“Maybe [China] can emerge from this quagmire, maybe she can wake up, under leaders who are more energetic, who are more able. If this huge body, today inert, is not dead, then let the world tremble, for the yellow peril is huge, and vision in the mind’s eye of millions of Huns descending as conquerors upon Europe has nothing delightful about it. This was one of the predictions of Napoleon on St Helena.”

-The Marquis de Nadaillac, 1904

Alas, it turns out Napoleon did not make any such prediction (research on that can be found at https://www.napoleon.org/en/history-of-the-two-empires/articles/ava-gardner-china-and-napoleon/). He did, however, warn the English against contemplating war against China, even though the Asian country was a pitifully weak giant in that day. That would not change almost until my own generation. Yet Westerners were starting to worry about the giant awakening already in the 1870s, although this did not prevent them from slaughtering each other in two world wars rather than making common cause against the Chinese.

Of course, until the postwar era there was really no need. For much of its millenia-old history, most of China’s military concerns were internal rather than external. The Han Chinese occupied an immense territory surrounded by mountains, deserts and sparsely populated neighbors. This changed drastically when the Mongols overran China in the 13th century, and Kublai Khan, the Mongol emperor described by Marco Polo, established a new dynasty. But the Mongols accomplished this with Chinese support (the country was divided in that era. The sheer size of China and its population made it too much for the Mongols to conquer and rule alone. And the Mongols only lasted a century.

[adrotate banner=”72″]

China’s last imperial dynasty, the Qing or Manchu, ruled for almost three centuries, and it was under its rulers that China reached both a zenith and later entered a period of decline. The Manchu rulers were, like the Mongols, technically foreign, but they adopted and blended into Chinese society much more than the Mongols had.

China was immensely powerful by the end of the 18th century but then entered a lengthy period of decline, resulting from corruption, conservatism and isolation. The country suffered a series of defeats on its periphery, such as the two Opium Wars, (1839-42 and 1858-60; at the hands of a semiprivate company no less), and the Sino-Japanese War (1894-95). Two 19th-century revolts led to some 20 million deaths. The Boxer Rebellion (1899-1901), an uprising against Western influence and the unequal trade treaties imposed on China, led to Western countries imposing even harsher terms. Still, reform efforts within the Qing dynasty were blocked.

In 1912, however, Chinese Republicans led by Dr. Sun Yat-Sen and others established a republic, but the country was unable to progress. Dissent about which direction the new republic would take eventually led to the Chinese Civil War (1927-49, although technically it never ended). Then Japan, which in 1931 had effectively annexed the Chinese province of Manchuria in 1931, began to conquer China in earnest in 1937, so that China, while divided between Communists and Nationalists, was forced to endure a barbarous invasion that did not end until the collapse of the Japanese war effort in 1945. Chinese suffering was far from over. The Civil War was now fought in earnest, the Communists winning in 1949 when the Nationalists fled to the island of Taiwan.

The Communist victory led to vast changes in China, of course, but the Communist state created in 1949 hardly resembles the China of today. In the 1980s Chinese leaders embarked on a vast series of reforms to create a system that combines socialism and capitalism. The country remains Communist in name but hardly in character; foreign investment is pouring in and domestic companies are creating vast fortunes. Economic growth has been spectacular. Yet that is not all that makes it a great time to be, as suggested by the headline, a Chinese strategist. China’s advantages are immense.

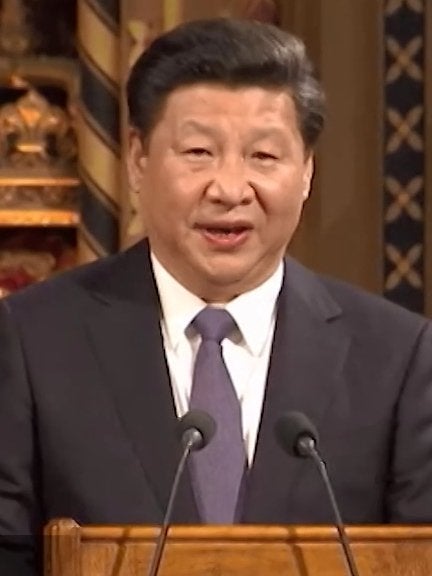

Probably the number one advantage that China has is the weakness of its strategic neighbors. Let us begin with its current friend, Russia. At the moment, Vladimir Putin and Xi Jinping, the respective leaders, are working hand-in-glove. This was also true of Hitler and Stalin before the Nazis invaded. But the Chinese benefit from their huge northern neighbor suffering from enormous internal weaknesses. Life expectancy and population are dropping, the economy remains weak and Putin’s dictatorship has nowhere near the stability of the Chinese Communist Party. In addition, China’s influence in Central Asia, formerly Soviet territory adjoining both countries, is growing.

To the southwest, China borders India, the only country with a population close to its own. In theory India could be a competitor for influence in south and east Asia. However, India is unlikely to fulfill that role. The two countries are not natural friends, having disagreements about the location of the border, not to mention China’s friendship with India’s neighbor and mortal enemy, Pakistan. But India is entering a complicated time. Hindu nationalists are attacking Muslims, both politically and, at times, physically, and it is unthinkable that Muslims will remain passive in the face of these attacks – and they may be a minority, but there almost 200 million of them.

[adrotate banner=”20″]

A final “strategic neighbor” is, well, us. While we are far removed from China physically, this is not the case strategically. America has four important alliances with nations close to China; Japan, South Korea, the Philippines and Taiwan. To the Chinese, Japan remains a historical enemy, Taiwan is really its property, and the Philippines are a rival for oil in the South China Sea, of which the Chinese claim its entirety. The Korean War never officially ended, and that was the one place where Chinese and American troops actually fought each other. And while the United States deploys an unparalleled amount of military firepower around the globe, the Chinese are fully aware and terribly happy about the extreme political divisions within the United States, which interferes with any long-term US foreign policy which might be aimed at restricting the growth of Chinese power. China spends fortunes on building infrastructures at home at abroad, such as the Belt and Road Initiative. (Just a thought: do you think maybe that underlies Joe Biden’s proposal to spend massively on our own infrastructure?)

So Chinese strategists should be feeling war and fuzzy. Or should they?

One thing you learn quickly in history is to beware of linear projections – the idea that because things are going in a certain direction, they will continue that way. Several things could make our Chinese strategist retire or request asylum. First of all, there is the question of how long China will remain a one-party state. Many Chinese have shown little stomach for radical reform because of the catastrophic crash that took place in Russia. However, the Communist Party could come under huge stress if there were a serious economic downturn. Second, the stability of China’s banking system is unknown – perhaps even to the government. Western countries suffered a massive financial crisis in 2008, and transparency here is infinitely greater than in China. Third, China’s dictatorship is a long-term disadvantage. Dictatorships can mobilize resources in a spectacular way; building gigantic factories or dams (think Three Gorges) was something the Soviet Union did very well under Stalin. But it ultimately proved the Soviet Union’s undoing and contributed to its demise. China’s economy is infinitely stronger than the Soviet Union’s was. A dictator might look at the economy and gigantic military and decide that a more aggressive posture abroad might be needed. This has proved the undoing of many countries in the past. And the less freedom there is, the more internal weaknesses might be hidden.

In conclusion, being a Chinese strategist these days feels good. Comrade Chen, it is perfectly alright to feel good. But for your own and your country’s security, not too good.

Hubert van Tuyll is an occasional contributor of news analysis for The Augusta Press. Reach him at hvantuyl@augusta.edu