Editor’s Note: This is a news analysis intended to help contextualize important issues of the day so our readers can better understand issues that are appearing in the news and so they can make more informed decisions about public matters. Writer Hubert van Tuyll is a professor of history at Augusta University. He holds a doctoral degree in American history from Texas A&M and a law degree from Duke University. In the interest of full disclosure, he is married to The Augusta Press Editor Debbie Reddin van Tuyll.

Three-and-half years ago President Donald Trump tweeted that his presidential pardon power might extend to himself. Reactions followed fairly predictable partisan lines. The answer to whether he can pardon himself is quite simple; maybe yes, maybe no.

Truth is that unless and until SCOTUS weighs in on the issue, we just don’t know. But two things stand out. First, pardoning has been controversial before. And second, pardoning himself may be neither profitable nor even useful for the president.

The Constitutional presidential pardon power is unilateral. According to the Constitution, “[The President] shall have Power to Grant Reprieves and Pardons for Offences against the United States, except in Cases of Impeachment.” Notice that nothing is said about who the president may or may not pardon. It is not necessary, by the way, for a person to have been charged with a specific “offence” for a pardon to be granted.

Don’t blame the Founding Fathers for not being clearer. Nobody can foresee every situation, and they did their best to keep our Constitution pretty short – the original document is only about 4,400 words long. It’s possible that they did not contemplate someone pardoning himself… There’s a fairly simple reason why they might not have made too much of the issue; there weren’t too many federal laws in the good old days, nor did they foresee how many there might be some day. So, it wasn’t that important. The Constitution was merely giving the president the same authority that kings and queens had enjoyed for ages.

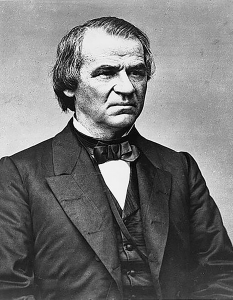

It’s not hard to find the greatest pardon controversy in American history. On April 15, 1865, Abraham Lincoln was assassinated, bringing Vice President Andrew Johnson into the presidency. The Civil War was just ending. Robert E. Lee had surrendered the Army of Northern Virginia only six days earlier; the other significant Confederate army would offer to surrender two days later.

Andrew Johnson was unusually placed as president of the victorious Union. He was a Southerner, representing Tennessee, and he was not a member of Lincoln’s Republican Party. However, the Republicans were confident in Johnson, who had often expressed his hatred of the Southern ruling class. Johnson was a tailor and a true advocate for the working man who had often talked of hangings for the Confederate elite.

Instead, Johnson began issuing pardons to the Rebels! Former generals and politicians came to the White House requesting a pardon, without which many of their civil rights could not be regained. Nor was it just ordinary men swept up in the war who were pardoned. For example, even Confederate Lt. Gen, Dick Ewell, a senior officer under Lee, clomped into the White House on his wooden leg and received a pardon. Ultimately, Johnson pardoned 14,000 Rebels. Not surprisingly, this triggered a political crisis that eventually culminated in Johnson’s impeachment and near-removal from office (he survived the Senate trial by one vote), but the pardons stuck.

So, a pardon of Trump by Trump might stick. Or it might not. Were it challenged (and it is not clear who could or would), his lawyers might argue that Trump the president and Trump the ordinary citizen are two different entities under the Constitution. Again, nobody can be 100 percent sure about the outcome. The bigger question for Donald Trump is whether he needs a pardon or whether a pardon would do him any good. Whether he has actually broken a federal law for which he could be tried is hardly a closed question. And more to the point, that is not where his greatest risks lie.

When the Founding Fathers met in Philadelphia to write our Constitution in 1787, they had a mess on their hands. For a decade the country had been run using a document called the Articles of Confederation and Perpetual Union, under which we were more an association of sovereign states than a “United” anything. The country could afford neither an army nor a navy and was humiliated by Spain and Britain in border disputes. The country could offer no help to Massachusetts when a rebellion broke out there. And in a scene Hollywood could not have invented, in 1785, the Continental Congress had to flee Philadelphia when an angry mob of unpaid Revolutionary War veterans stormed the city. Congress had no power to tax, so it could not pay the veterans what they were owed, nor could it hire troops to protect itself. So, when they met in 1787, they agreed with surprising speed that state sovereignty had to go.

The states, however, had no intention of disappearing from the constitutional landscape. While the states eventually agreed to have a strong federal government, there were several obvious items in the Constitution that were designed to prevent federal overreach. An Electoral College was created that prevented national election of a president (we vote only by state) and protected the smaller states somewhat. A Senate was established in which all the states were equal, and the state legislatures originally voted on who would serve a state in the U.S. Senate. (Alas, no longer the case.) States were allowed to continue to have militias. The 9th Amendment effectively allowed state to have broader Bills of Rights than the national government had. The 10th Amendment stated that powers not delegated to United States belonged to the individual states, or the people.

What does this have to do with Donald Trump? Collectively, all these state powers mean that states can continue to do what they wish so long as it does not interfere with legitimate federal action. The pardon power deals with crimes against “the United States,” meaning federal law. Each state has its own laws. A presidential pardon is no bar to state prosecution.

Trump is vulnerable here – and not because of his presidential actions. Those are, in most cases (but not all), beyond state jurisdiction. However, as a national and global businessman, he could face difficulties. Suing a president even for non-presidential matters is difficult. As an ex-president, he will be in a different position. Most presidents have been statesmen, soldiers or lawyers. There wasn’t much to sue them about. Trump’s businesses have been accused of a number of legal violations in several states. Texas and Florida come to mind. It may be that Trump can shield his person behind his corporations, but his wealth might be on the line. Whether those cases were brought because of a genuine legal violation, or for revenge, or simply because bills were unpaid, makes no difference. His money will be on the line.

So, my advice to the president is quite simple. First, hire a top-notch law firm with Wall Street cred. He should probably not rely on the lawyers he used in the past few weeks. Their success rate has not been good. Second – and this may be more difficult for him – listen to those lawyers and follow their advice. Finally, given that he has a global business reach, if everything goes wrong, maybe he should remember that a number of respectable countries do not have extradition treaties with the United States.

Hubert van Tuyll is an occasional contributor of news analysis for The Augusta Press. Reach him at hvantuyl@augusta.edu