Editor’s note: Today is the 84th anniversary of the Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor. Historian Hubert van Tuyll describes that day, why the Japanese were bold enough to attack and the consequences of the day.

“A date which will live in infamy” those were the words with which President Franklin D. Roosevelt described the Japanese attack on the Pearl Harbor naval base on Dec. 7, 1941. (watch the speech here)

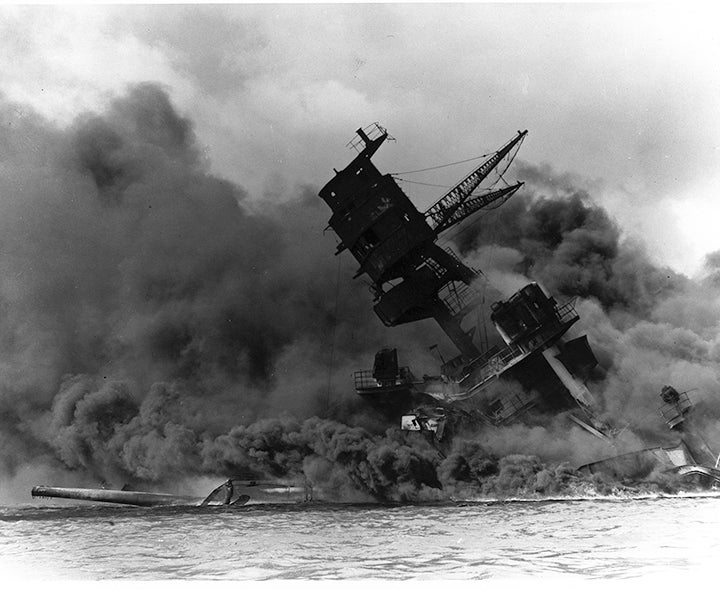

Shortly before 8 a.m., more than 350 airplanes from six carriers of the Imperial Japanese Navy came roaring toward the U.S. naval base, inflicting heavy losses on the completely unprepared American warships.

The Japanese inflicted heavy losses. Four battleships were sunk, and four others were seriously damaged. More than 2,400 Americans lost their lives, including civilians killed by friendly fire, inevitable in the chaos of a surprise attack. Aircraft losses were even more serious, with almost 350 planes put out of action. The suffering of many of the victims makes hard reading. Three men were trapped in a watertight compartment in West Virginia for 16 days. There was no way to rescue them.

What did Japan attack?

Why did the Japanese do it? Why did they make an enemy of the world’s greatest industrial power, while their army was already at war deep in China? The attacks Japan launched in the Pacific did have some logic behind them, faulty as it turned out to be. Japan is poor in natural resources. The United States had frozen Japan’s financial assets in America, which made it impossible for the Japanese to continue buying oil from us. Oil and other natural resources could be found in the Dutch East Indies and Southeast Asia.

Furthermore, the “window of opportunity” looked wide open. Japan faced four possible major enemies if attempted a Pacific expansion; the USA, the USSR, France and Britain. France had been overrun by ally Nazi Germany in the summer of 1940. Britain was barely hanging on alone against Nazi aggression since then. The Soviet Union had been invaded by Nazi forces in June of 1941 and looked like it was about to collapse. This left only the United States as a completely free and clear adversary.

So, why not ignore the United States and attack the French, British and Dutch colonies where the natural resources were? The Japanese strategists advocating aggression made an assumption – always a dangerous thing. They assumed that if they attacked the European colonies, the United States would join the war – especially as Japanese forces would have to pass our own Asian colony, the Philippines.

Roosevelt administration knew of the possibility

The Roosevelt administration was aware of Japan’s possible aggressive intentions and had taken steps to discourage them. Cutting off the money was one step. Another was moving the Pacific Fleet from its bases on the west coast to Hawaii. This was intended to deter aggression. Obviously, this failed. The problem with deterrence is that it makes assumptions about how your adversary will react in a crisis.

Japan was not a dictatorship. There were, however, powerful forces in favor of aggression. Foreign Minister Yosuke Matsuoka was a strong supporter of an alliance with Hitler and Mussolini. Matsuoka was out of office before Pearl Harbor, but this did not weaken the pro-war party. The minister of war, General Hideki Tojo, succeeded the pro-peace Prince Fumimaro Konoe as Prime Minister less than two months before Pearl. From then on, aggression was inevitable.

Ironically, the Imperial Japanese Navy, which would have to carry the brunt of the Pacific war, was not nearly as pro-war as the army. Many senior officers were uncertain about the prospects. This included Admiral Isoroku Yamamoto, who was tasked developing a plan that would enable Japan to deal with American and British naval forces.

Yamamoto opted for a surprise attack on Pearl Harbor, believing that destroying the United State’s Pacific Fleet would delay any American counterattack long enough for Japan to build a defensive perimeter in the Pacific. That he would opt for a surprise attack was not a surprise, as Japan had successfully done this in 1904 during the Russo-Japanese War. Prince Konoe asked Yamamoto whether the plan could work. Yamamoto responded: “If everything goes as planned, I can run wild for a year and half. After that, I can promise nothing.”

Hardly the words of an optimist, or of an admiral who really wanted to launch the attack. He never said that he feared that he had woken a sleeping giant, but he was highly familiar with American resources and capacity, having studied at Harvard. But to many people – on both sides – his initial operation looked like a wild success. Whether it was or not, surprise was certainly achieved. Why?

Why was Pearl caught by surprise?

In fact, there were so many reasons why the base was caught by surprise that it would be a far greater surprise if it hadn’t. There were at least six factors that played into the disaster:

- Torpedo design. Pearl is shallow – and aerial torpedoes would hit the bottom of the harbor before they would reach the warships. But in 1941 the Japanese had redesigned their torpedoes making it possible to use them at Pearl.

- The size of the Pacific. That Japan might launch an attack was certainly foreseen – but where? Hawaii? Alaska? The Philippines? Malaya and Singapore? The Dutch East Indies? Australia and New Zealand?

- The Philippines. Viewed (correctly) as the most vulnerable American possession in the Pacific, the American plan was for the Pacific Fleet to sail westward to rescue our position there.

- Fuel. For the Japanese battlefleet to reach Hawaii, it would have to stop in midocean to refuel – an incredibly risky thing to do.

- Knowledge, or lack thereof. The code which the Japanese were using was not cracked until 1944. In addition, the telegraph operators on their warships were back home! Believe it or not, it was possible to recognize individual wireless telegraph operators from the way in which they tapped their key. So, all these men were sitting at base, tapping messages to each other. This did not completely fool the U.S. Navy, but nobody knew where the Japanese navy was.

- Countermeasures. The American Army commander, General Walter Short, had all his airplanes parked close together to make it easy to guard against saboteurs. This made it easy for Japanese pilots to destroy planes by the dozen. Admiral Husband Kimmel kept his battlewagons parked in position in harbor because going out without air cover would be suicidal. It also made the battleships easy targets. However, Kimmel saved a lot of lives in the process. Most of the sailors in Pearl survived. Almost three quarters of the men lost were in a single ship (Arizona, which ironically was scheduled to leave Pearl in another day for extensive updating on the west coast).

Often the question is asked: How much did the U.S. government know? How much did the president know? The short answer is – they knew some things. The military suspected, and the president was informed, that the possibility of war with Japan was very high. So, the next question becomes: Why did they not inform the commands at Pearl?

The short answer is – they did! Twice! Warnings were sent on Nov. 27 and Dec. 3, with language such as “This dispatch is to be considered a war warning” and “hostile action possible at any moment.”Besides, the vulnerability of Pearl was no secret. In 1938, the carrier Saratoga had successfully evaded detection and “attacked” the base during a war game. But the warning telegrams did not specify Hawaii as a target, because officers in Washington did not believe Japan would attack such a far away target. Neither did the commands in Hawaii.

Surprise notwithstanding, the attack was a failure. The war resulted in the complete defeat of the Japanese empire, the entire destruction of major cities, and seven times as many deaths as the United States suffered. At Pearl, only two major warships were permanently lost to our Navy; battleships Arizona, which was blown up, and Oklahoma, which capsized and was found to be beyond repair. No carriers were in port. Worse (for Japan), the repair and refueling facilities were undamaged, so the base could continue to function. This was partly because Japanese commander Chuichi Nagumo, worried about the vulnerability of his carriers, refused to order a third strike.

A third strike had been urged by a number of officers, including one Mitsuo Fuchida – the sole flying officer at Pearl to survive the war. After the war, he converted to Christianity, became a Baptist minister and spent much of his in the United States preaching and proselytizing.

Hubert van Tuyll

Augusta University (Emeritus)