Editor’s note: October is breast cancer awareness month. Breast cancer related stories have been running on Wednesdays and Sundays in The Augusta Press.

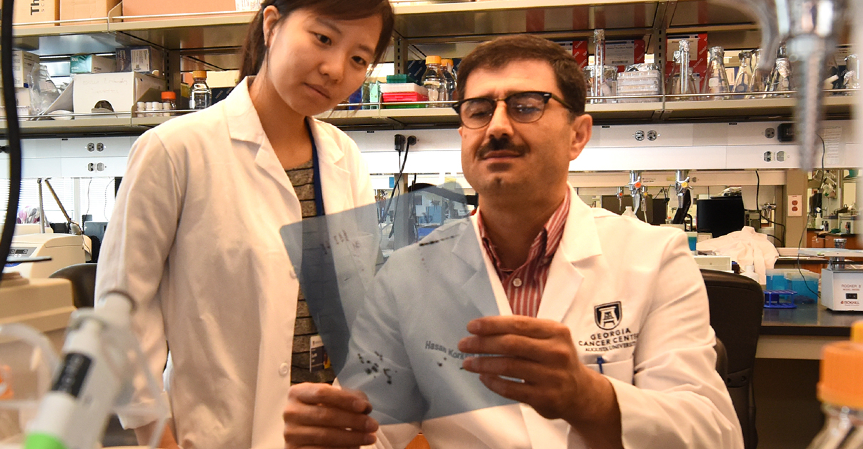

Researchers at the Georgia Cancer Center are focusing on a specific molecule in tumor cells in hopes of understanding what role it plays in a particularly aggressive form of breast cancer.

Dr. Hasan Korkaya, an associate professor in the Department of Biochemistry and Molecular Biology at the Medical College of Georgia, and his team of researchers recently received a $1.76 million grant from the National Cancer Institute to study triple-negative breast cancer.

“Ninety-nine percent of the cancer-related deaths are from metastasis,” said Korkaya, who has been researching triple-negative breast cancer at Augusta University since 2013. “Unfortunately, triple-negative is the most aggressive and metastatic subtype.”

According to the American Cancer Society, the form of breast cancer is called triple-negative because the cancer cells do not have estrogen or progesterone receptors and do not produce an oncogene called HER2.

[adrotate banner=”55″]

Triple-negative breast cancer is frequently found in African American women, women under the age of 40 and those who test positive for the BRCA-1 gene. Between 10% to 15% of breast cancers are triple-negative, the cancer society’s website said.

“Triple-negative breast cancer is considered an aggressive cancer because it grows quickly, is more likely to have spread at the time it’s found and is more likely to come back after treatment than other types of breast cancer. The outlook is generally not as good as it is for other types of breast cancer,” according to the website.

Korkaya’s previous research has revealed the HSP-70 molecule as one of the culprits in this particular form of cancer’s devastating path.

Korkaya said cancer cells in the case of triple negative breast cancer seem to trick the body’s immune system so that it doesn’t attack the cancer. Instead, it seems to switch sides as it were, aligning with the cancer cells and allowing them to grow and spread to other parts of the body previously unaffected by the disease.

He said this molecule seems to protect the cancer tumor cells from various types of treatment such as immunotherapy.

Understanding how HSP-70 works could help researchers in the development of drugs that can disable the efforts of the molecule.

It’s a five-year grant.

“Hopefully if we are successful and if everything goes well, we’ll go for a renewal for another five years, and perhaps in the second five years, we’ll try (to see) how we can translate that into clinical setting,” he said. “But these kinds of studies take unfortunately a long time. A drug coming from basic research to a patient’s bedside take 15 to 20 years and millions of dollars in research.”

Charmain Z. Brackett is the Features Editor for The Augusta Press. Reach her at charmain@theaugustapress.com

[adrotate banner=”51″]