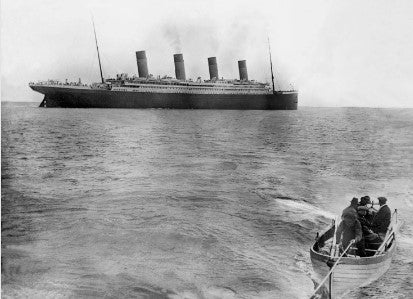

It was 111 years ago today when Augustans and the rest of the world learned that the world’s largest ship, the RMS Titanic, had foundered 500 miles off Newfoundland on its maiden voyage, taking 1,503 souls with her.

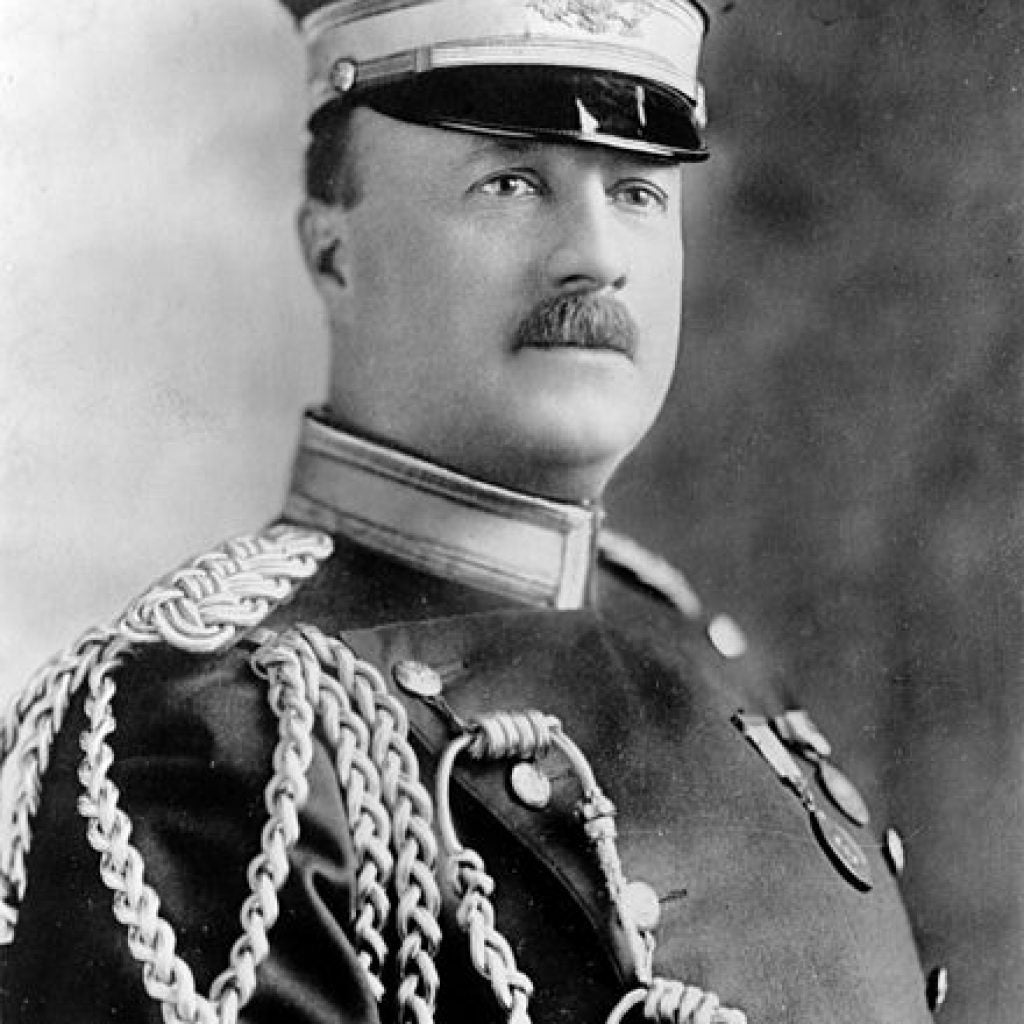

Augusta built the first memorial in North America to a victim of the sinking in the form of the Butt Bridge, which honors Archibald Butt, an Augusta native who died a hero that fateful night. Butt was likely not the only first class victim known to Augustans as the Garden City was the Gilded Age winter playground for the wealthy Northern elite.

Over time, several myths have sprung up, romanticizing the tragedy and attempting to find the person or persons at fault. Public interest in the sinking soared when Robert Ballard, who was on a top secret U.S. underwater military mission, discovered the wreck in 1985 and the interest reached a zenith with the 1997 release of James Cameron’s blockbuster movie “Titanic.”

One myth that is rather easy to debunk is that Titanic was, by order of White Star Line Managing Director Bruce Ismay, attempting to set a speed record. According to Titanic historian Doug Spence, the ship was purposefully not built for speed.

RMS Lusitania and RMS Mauretania, Cunard’s “greyhounds” of the ocean, were the fastest liners on the water, but both suffered terrible shaking from amidships to the stern when the ships were traveling at full speed. Attempts to strengthen the frames helped, but the problems were never fully resolved.

Titanic, on the other hand, was built for comfort,k not speed. Ismay testified in both the American and British inquiries that, to his knowledge, the last two boilers had not been lit during the voyage.

Another myth is that the Titanic Bridge ignored multiple warnings from other ships that ice was in the area. It is true that messages were sent, but most were warning of “growlers,” which are relatively small bergs the size of a grand piano and could not inflict the kind of damage that ultimately sank the ship.

The SS Mesaba did send a message warning of what was likely the berg Titanic hit, but there was a mistake on the part of the wireless operator on the Mesaba. Messages of urgent importance were supposed to be headed with “MSG,” which meant the message should be taken immediately to the bridge.

Most wireless operators were young and inexperienced, and the Mesaba’s message was not coded “MSG.” Due to this oversight on the part of Mesaba, it is likely that the wireless operator on the Titanic, Jack Phillips, thought it was simply another spotted growler and did not make it a priority.

Phillips himself was not inexperienced; in fact, the Marconi wireless set broke down during the voyage, and Phillips broke company rules and spent almost eight hours making repairs. Had Phillips not violated company rules and fixed the set, everyone on the ship would have perished.

According to Spence, onboard it became a situation of whether to believe what someone is telling you or what you see with your own eyes. While the messages were coming in, lookouts on the great ship had not seen even the first growler.

“I find it ironic that the first iceberg they saw was the one they hit,” Spence said.

The White Star Line was condemned at the time for not having enough lifeboats onboard; however, Spence says the lifeboat issue is largely a case of hindsight being 20/20.

The Titanic actually carried more lifeboats than were required by the Maritime Board of Trade. The bigger issue, according to Spence, is that the boats were lowered half full because few passengers were willing to trade the warmth and perceived safety of the big ship in favor of a tiny little boat bobbing around in the ocean.

“If they could have just coaxed more people into the boats they had, probably at least 500 more lives would have been saved, and that is the great tragedy,” Spence said.

Maritime historian Mike Brady points out that in those times, the watertight compartment technology led most experts to consider the ship itself the lifeboat.

“The first line of defense was the ocean liner itself. Much greater importance was put on watertight subdivisions providing ways to seal off damaged parts of the hull. Using a lifeboat was an absolute worst case scenario, a last resort,” Brady said in his popular “Ocean Liner Designs” documentary series.

Lifeboats were, at the time, thought of as a way to ferry between ships.

Both Spence and Brady agree that more lifeboats would likely have not made a difference since the last boat, number 4, left the ship mere minutes before the final plunge. Collapsibles A and B literally floated off the sinking deck, so any remaining boats tethered to davits would have gone down with the ship.

One chilling factual story related to the so-called “unsinkable ship” does cause one to wonder.

In 1898, a struggling American author named Morgan Robertson published a novel titled “Futility.” Robertson divized a ship with almost the exact dimensions as Titanic and the same number of watertight compartments. The lifeboat complement on the fictional ship would only accommodate half of the total passengers onboard.

Lifeboats would not be an issue because Robertson labeled his ship “unsinkable.”

In the book, the ship is loaded with the wealthiest of the wealthy and sails from Ireland on its maiden voyage in the month of April, steaming at full speed toward an ice field.

Of course, the ship sank, killing 1,500 people.

According to the late Walter Lord, author of the book “A Night To Remember,” Robertson meant for his novel to be a commentary on and a metaphor of the futility of life. He likely froze in horror when he read the newspaper on April 15, 1912.

The name of Robertson’s fictional ship was Titan.

Scott Hudson is the Senior Investigative Reporter and Editorial Page Editor for The Augusta Press. Reach him at scott@theaugustapress.com