Editor’s Note: Sandy Hodson’s 14-part investigation into how justice is administered in the Brunswick Judicial District continues today with Part 3. This story looks into some of the scandals that have rocked the Glynn County Police Department as well as another case where the evidence and the outcome seem peculiarly out of sync. Parts 1 and 2 can be found elsewhere in The Augusta Press website. Series stories will be published on Sundays and Thursdays.

By July 2020, Brunswick Judicial Circuit District Attorney Jackie Johnson and the Glynn County Police Chief John Powell were both in hot water for the Ahmaud Arbery case.

Johnson insisted she did the right thing by handing the Arbery case over to fellow prosecutor John Barnhill, the district attorney in the neighboring Waycross Judicial Circuit. She said she’d have a conflict of interest because one of the defendants, Greg McMichael, was formerly an investigator in the DA’s office. Others thought there might be other reasons. After all, Barnhill had been Johnson’s mentor when she was new to prosecuting, and Johnson hired Barnhill’s son as one of her assistant district attorneys.

Golden Isles Injustice

Part 3

Glynn County Police officers pointed the finger at Johnson, saying she was the reason Greg and Travis McMichael and William Bryan weren’t arrested after Arbery was murdered. Johnson fired back the GCPD was being vindictive because she had indicted Powell and several of his top staff within days of Arbery’s killing for their alleged roles in covering up misconduct and criminal acts for officers.

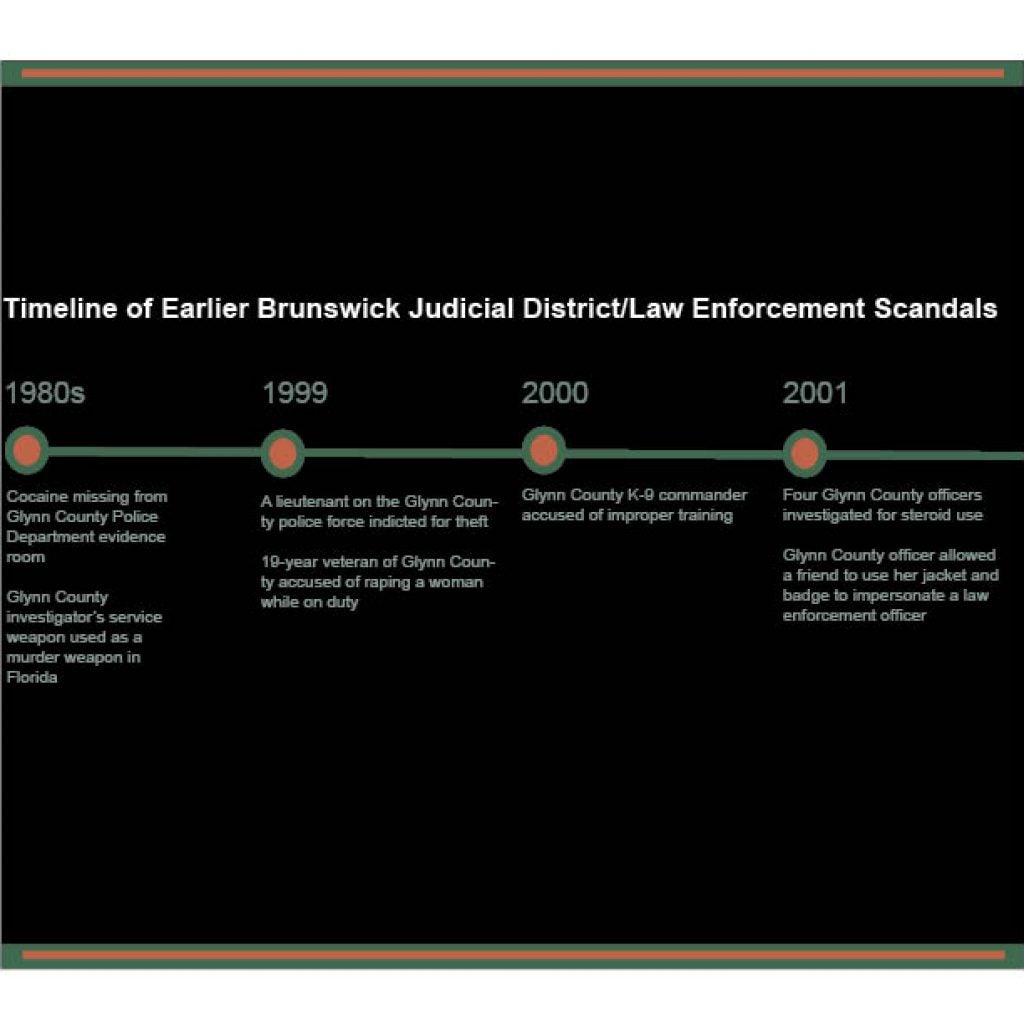

Scandal has vexed the Glynn County Police Department for decades. David Dowdy, the investigator who arrested Larry Lee for his part in the 1986 Charles Moore murder, said when he was on the force back then, a kilogram of cocaine went missing from the evidence room, and an investigator’s service weapon turned up as a murder weapon in Florida homicide.

In 1999, a lieutenant was indicted for theft, and a 19-year veteran officer resigned after he was accused of raping a woman while on duty. In 2000, the commander of the K-9 unit resigned after allegations of improper training arose.

In 2001, four officers resigned in the midst of an investigation into whether they had been using steroids. Another was dismissed after it came out that she allowed a friend to use her jacket and badge to impersonate an officer, The Brunswick News reported.

It was during those early scandals that Lavelle Lynn and Robert VanAllen were lured to their deaths on Labor Day, Sept. 3, 2000, on what’s still an isolated dirt road surrounded by trees and swamp land. The murder site was in Glynn County, just a mile or so from its western border with Brantley County.

The GCPD concluded that Lynn and VanAllen were killed in a robbery. Lynn’s wallet containing a few hundred dollars was taken. Lynn was killed by a single bullet fired into the back of his head that passed straight through and exited right between his eyes. VanAllen was shot twice, and either bullet would have proven fatal. But his killer also held the barrel of a 25-caliber handgun close enough to his left ear to leave power burns as a third bullet entered his head.

The killings were quick. Richard Pittman and his son, Dustin, were riding their ATVs that day and followed behind Lynn’s tow truck onto Bladen Road. The father estimated they were 10 minutes or less behind the victims when he and his son reached the railroad tracks and saw the tow truck backed up beside the tracks. A small white or light blue car that he believed most closely resembled a 1985 Honda Accord Hatchback, was directly behind it.

MORE: Glynn County justice issues go back decades before Arbery case

The father said a young man with a blond crewcut was standing near the tow truck’s driver’s-side door. A second, smaller, dark-haired man stood near the small car. Pittman said he thought about stopping to see if they needed help, but he waved instead to the blond man who waved back.

A man training his hunting dogs in the area heard several gunshots that morning, which wasn’t unusual there. He specifically recalled looking at his watch when he heard the shots. He was trying to round up his dogs to leave before the day got too hot as it does at the end of summer in Georgia. It was 10:30 a.m., his watch showed. Less than 20 minutes later, he drove down Bladen Road and discovered Lynn’s and VanAllen’s bodies. Although the murder scene was as far west as one can get in Glynn County and still be in the county, two GCPD officers arrived in less than 15 minutes.

Officers would describe their work at the crime scene: how they carefully and meticulously took measurements and photographs, made sketches and logged evidence. They insisted access to the scene was limited and all evidence was preserved.

However, Mike Mears, former death penalty defense attorney who was the first director of the state’s public defender system who is now a professor at Marshall School of Law in Atlanta, said the scene was treated so poorly, he uses the case in one of his classes as an example of how many things can be done wrong at a crime scene. The man who found the bodies said he counted 22 police cars at the scene at one point.

Crime scene photos show many of the 34 people at the scene that day in areas that were supposed to be off limits to all but a few, including Brantley County Sheriff Cordell Wainwright. Wainwright got to the scene before the lead investigator, although the sheriff said he was on the other side of Brantley County laying a trap for marijuana growers when he heard about the killings.

Lynn’s friends and family members told investigators that that Lynn seemed troubled in the days before the killings, that he needed a large amount of money and that he was unusually nice to others. His wife said he talked of going back to church.

Lynn bought and sold used cars most of his life. VanAllen worked for him and lived on his property, which, from a sky view, looked like a junk car graveyard. VanAllen raced cars that he and Lynn worked on. Lynn loved car races, chicken fights and his family, friends told sheriff and GBI investigators.

His brother-in-law, Lecester Woodall, said the used-car business gave Lynn cover and transportation for Lynn’s real money maker for much of his adult life: moving narcotics.

MORE: History repeats itself two decades later in Dennis Perry’s capital murder case

Woodall said Lynn had transported drugs since the 1960s. He had seen Lynn with rolls of hundred-dollar bills “that could choke a horse.” Lynn didn’t talk about his business, and Woodall said he didn’t ask. But he believed Lynn backed away from running drugs after he was busted in 1988. That was his second conviction, and he was still on probation for the first case, according to Brantley County court records. He had been caught only with marijuana, but on the second conviction, he was sentenced two years in prison.

Woodall said Sheriff Wainwright kept Lynn in the local jail, sending him out to do masonry work during the day. Lynn isn’t listed as having been in prison, according to the state’s Department of Correction. Because a felony sentence is a state matter, incarceration is usually served in a state prison.

The Friday before the Labor Day murders, Woodall said Lynn crossed the street to visit. He could tell Lynn was mad, and he offered to smoke a joint and drink a beer with him. Lynn told him he had to grab a shotgun to run Wainwright off his property, Woodall said.

Labor Day morning around 9 or 9:30 a.m., Lynn, VanAllen, Lynn’s wife, Leona, and his daughter Belinda Whitlow were drinking coffee and chatting, just cutting up, Whitlow said, when the phone rang. Whitlow answered and handed the phone to her father because the caller asked for Lavelle.

His wife and daughter heard Lynn protest the caller needed to “call rotation.” Law enforcement agencies generally keep a list of local tow truck operators that officers use to recommend towing services for disabled vehicles. They rotate their recommendations to keep the distribution equal.

Then Lynn said, “Call Jo Jo.”

Jo Jo Horton was a friend of the Lynn family who owned a wrecker service. The caller must have known Horton since Lynn didn’t provide a last name or phone number. Whatever the caller’s response, Lynn gave in. Lynn asked where the caller was, and he asked where the vehicle was. Lynn repeated back what the caller said: the pay phone at Paige’s on Post Road near the Golden Isles Speedway, and Bladen Road at the railroad tracks.

Lynn changed clothes before leaving, and VanAllen ran down to the convenience store to change coins into dollar bills. About 9:45 to 10 a.m., Lynn pulled the tow truck out of his drive and over to Woodall’s place.

Woodall and his son were working on a truck motor. Lynn asked his brother-in-law to go along on the call. Lynn had never asked him to go on a job before, Woodall said. Woodall declined. He needed to get his truck running. Lynn backed the tow truck to his drive and Woodall noticed Lynn seemed to be unloading items. Lynn then came back, Woodall said.

“I need you to go,” Woodall quoted Lynn as saying the second time.

Again, Woodall turned him down. Lynn asked a third time.

A while later Woodall and his son were still working on the truck engine when he heard screaming and crying from Lynn’s place across the road. He went over and learned Lynn and VanAllen had been shot to death. He walked past Lynn’s bedroom that day and noticed a pile of items usually carried in a man’s pockets, and in Lynn’s case, that included a Derringer.

“Lavelle carried that Derringer everywhere, everywhere,” Woodall said.

Days earlier when Lynn had given him a tow after his truck engine blew out, Lynn had a 380 or 9 mm Velcroed under the dash, a sawed-off shotgun and a 38 on the seat – in addition to the Derringer he always carried, Woodall said. Lynn also asked him during that trip if he knew where Lynn could get $15,000 in a week. Woodall said he told Lynn the only way he knew to get that much money in so little time involved what Lynn had given up.

When GCPD officers searched Lynn’s tow truck after the murders, no weapons were found. Woodall thinks Lynn took all the weapons out because he was supposed to meet a law enforcement officer that day. As a convicted felon, Lynn could be arrested just for carrying a gun. Woodall also thinks that’s why Lynn was so persistent in asking him to go that morning. Woodall isn’t a felon. He could have brought a gun.

According to the GCPD investigative files, there were suspects, a lot of them, and that was problematic. Investigators chased after numerous leads, some of which appeared promising but didn’t lead to an arrest. They put out a press release, and they posted flyers of a composite drawing of one of the men at the crime scene. The father who passed the tow truck on Bladen Road described the man for a GBI sketch artist. Investigators also put out a press release stating that the security video from Paige’s convenience store near Bladen Road was being sent to the FBI to enhance the quality. The GCPD asked if anyone had been to that Paige’s that morning to call the department. Someone had used a pay phone in front of the store to call Lynn’s home Labor Day morning.

Still no arrests.

A month later, Nov. 7, 2000, GCPD Chief Carl Alexander called in the GBI. The GBI agents began to focus on Rodney Evener and his son Ronnie who moved into Lynn’s and VanAllen’s homes, respectively. VanAllen had lived in a trailer on Lynn’s property. Four months after her husband’s murder, Leona Lynn told people she intended to marry Evener.

The Eveners and Leona Lynn told people her husband and Evener had been friends for years, but those close to Lynn before his death had never heard of Evener. One of Lynn’s daughters told agents that Rodney Evener was a blessing for her mother, and that Ronnie Evener was so kind-hearted, he would never hurt anyone. The GBI chipped away at Ronnie Evener’s alibi for the day Lynn and VanAllen were shot to death. His father said he had been in Pennsylvania.

As the spotlight hit the Eveners, Wainwright’s chief deputy passed along a tidbit for GCPD. A .25-caliber handgun, the same caliber used to kill VanAllen, was stolen during a burglary in Brantley County on May 8, 2000. That burglary was at Woodall’s home. He told GCPD that Woodall believed his son broke into his house, a statement Woodall continues to deny.

On Feb. 14, 2001, the lead GCPD officer on the Lynn/VanAllen case, Tom Tindale, knocked on Woodall’s door. He asked about the burglary and the stolen guns. With Woodall’s permission, Tindale and the other officers with him searched the yard and collected spent shell casings and bullets. The GBI laboratory ballistics examiner told Tindale it was close, but the shells and bullets he collected at Woodall’s place were too degenerated to match.

Woodall’s son David took Tindale and the others to a spot on Ten Mile Road where the family had done some target practicing with the handguns. He pointed out a couple of objects he remembered shooting at.

David Woodall testified the day he took the officers to Ten Mile Road, one of the offices walked back into the area he had indicated and returned with a bullet. It was in perfect condition, he quoted the officer of saying.

Tindale testified he and other officers went back to the target shooting area on Ten Mile Road and returned with five spent .25-caliber bullets. Although they were searching for what they thought could be evidence in a double homicide, they didn’t document the collection, in words, photographs or even a sketch.

On March 20, 2001, the GBI ballistics examiner told Tindale one of those five spent bullets was a match for a bullet taken out of VanAllen’s body.

Nearly a year earlier, on May 8, 2000, Woodall and his wife called the Brantley County Sheriff’s Office. While they were at work, someone had pried open the back door. The thieves took some cash and handguns, including a 25-caliber. The Woodalls expected eventually to hear from a deputy sent out to take a report.

But within minutes Sheriff Wainwright, his chief deputy and an investigator were there.

“They said they had just been nearby when the call came in,” Woodall said.

He didn’t believe them, didn’t understand the special attention. Woodall really didn’t understand why Wainwright said he followed footprints from his back door to the house next door. He said he knew it was a lie because he had watched as Wainwright went outside and walked off a few yards away, smoked a cigarette and came back inside.

In response to an Open Records request, the Brantley County Sheriff’s Office turned over copies of all burglary reports from March through June 2000. There were 42 of them in the county with fewer than 15,000 residents. Homes, businesses, a school and even a church were hit by burglaries. But the only burglary crime scene Wainwright went to was at the Woodalls’ place.

There was something else, Woodall told The Augusta Press. Not only were two guns and ammunition for each stolen, so were the ownership papers of the weapons, Woodall said. Papers that the Woodalls keep in the safe with the guns were laid out on the bed, Woodall said. The thieves only took the documents for the handguns. When Woodall went to retrieve copies of the documents that he kept at his work office – he always stressed to his children the importance of keeping copies of important personal documents in two separate locations – they were gone, too, Woodall said.

Without the documents, Woodall couldn’t give the Brantley County Sheriff’s Office the serial numbers of the handguns. But when the guns were entered in the criminal information system a day later, the serial numbers were listed, according to the supplemental report.

An additional note about the incident report of the Woodall burglary. In the last line, Chief Deputy David Stallings wrote that he had a suspect but couldn’t name him at that time.

Woodall didn’t hear anything from Brantley County Sheriff about the burglary until an officer accompanied the GCPD detectives knocked on his door Feb. 14, 2001.

Sandy Hodson is a staff reporter covering courts for The Augusta Press. Reach her at sandy@theaugustapress.com.