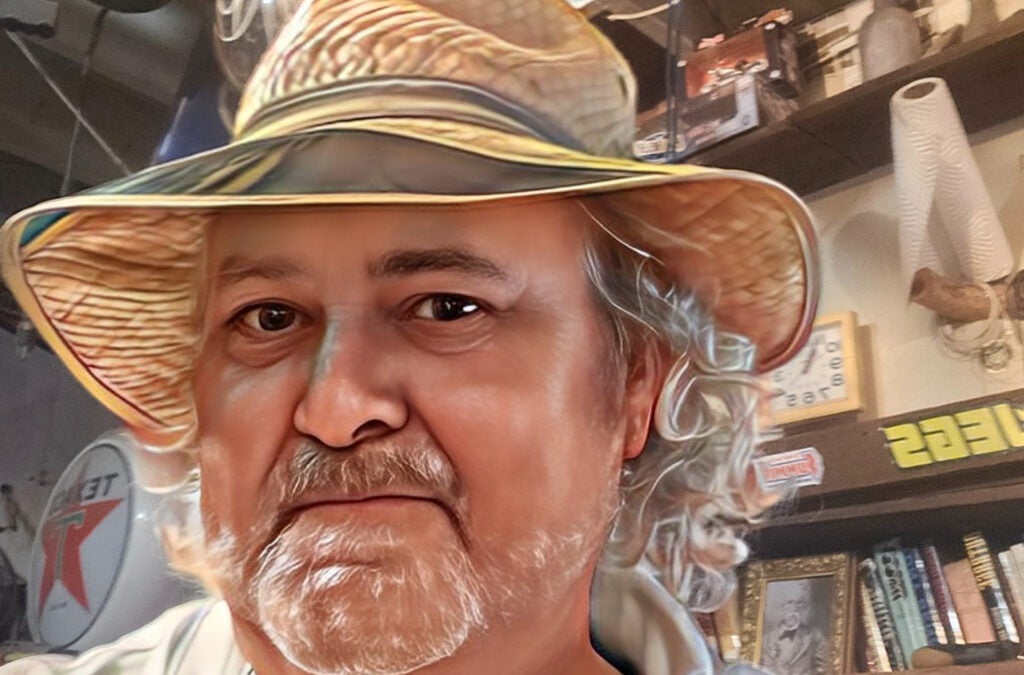

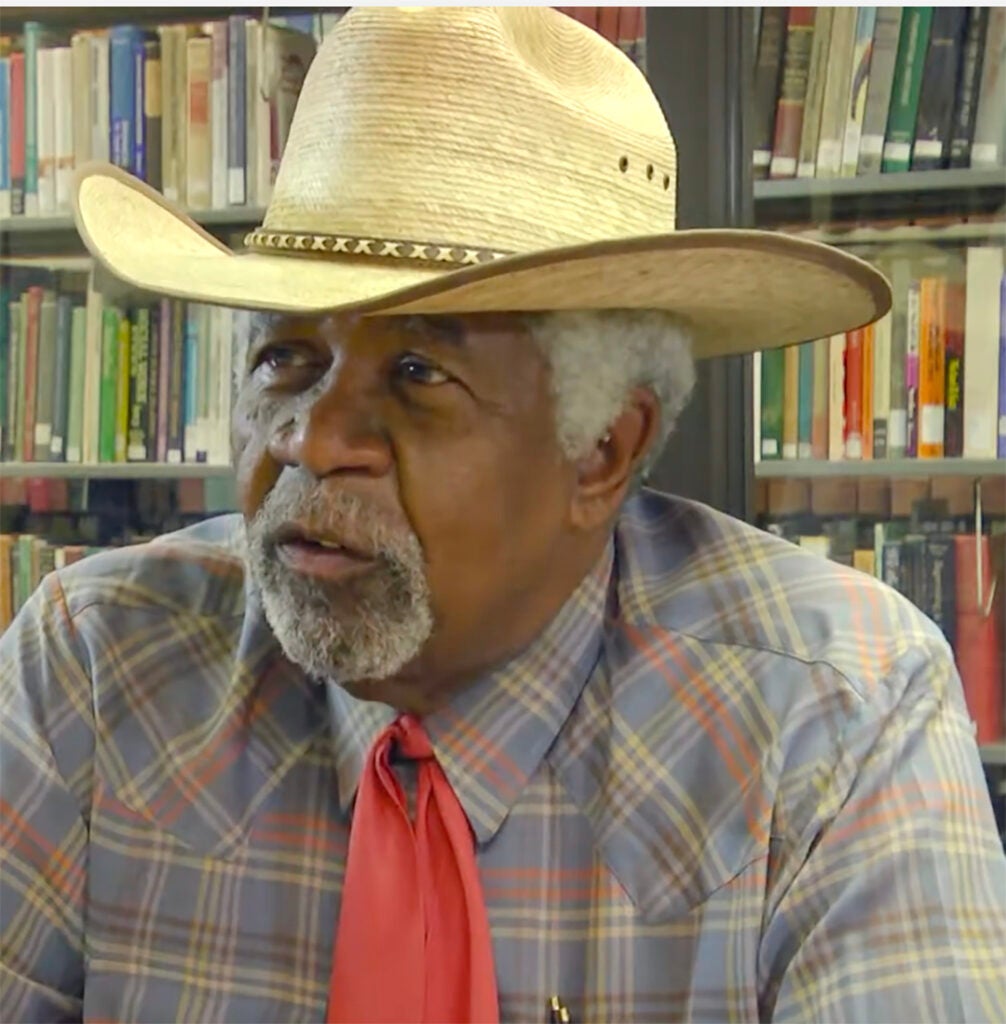

The death of my friend and former teacher, Cowboy Mike, set me to thinking about his mission and purpose in life and how irreplaceable this man is to our community.

Cowboy Mike sat on my Honors Program committee at the then Augusta State University. My honors thesis was an interdisciplinary look at race and culture in the form of both a fictional novel as well as a play adaptation.

The “Cliff Notes” of the book is that it is about how a rural Georgia town reverts back to its old segregationist ways when a broken down, and haunted, Antebellum plantation mansion is restored. The manuscripts would never be published today, certainly not by an academic institution, because of language and situations.

The climax of the story is when an innocent Black boy is lynched.

It was Cowboy Mike’s job to make sure that I got my history correct and that I did not cut corners to avoid offending modern sensibilities. He refused to allow me to place victimhood status on an entire race of people and had me focus on how segregation and racism went both ways.

Cowboy insisted I use the “N-word” (spelled out) as well as the term “Cracker-Ass Cracker,” because that was the way people talked in the days of segregation. He also wanted me to focus on a broad scope and on how the lynched Black boy in the novel was actually a metaphor for “the death of innocence.”

For me, it was tortuous work, for I was writing something that was so far out of my element, and it was painful to think that people once behaved in such a manner. When the folks at ASU approached me about staging the play, I declined, saying that some plays are meant to be read and understood, but never performed live.

Swinging Innocence was such a literary work.

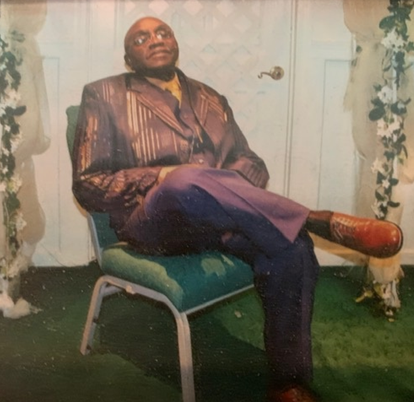

Cowboy Mike reminded me a lot of my friend and spiritual mentor Rev. Jackson Parks. Both men grew up in the segregation and Civil Rights Eras, and both would follow a life-long path of reconciliation with the past and mentorship of what they considered the future: our children.

A common trait of both men was that they were not bitter about the past and sought to understand it, rather than rail against it.

Jackson once recalled how his family was on a road trip to Alabama when he was a boy. The then 5 year-old Jackson told his father that he needed to go to the bathroom, but every gas station they came to did not have a “Negro” bathroom.

The family was traveling through an area that, should they have pulled over to allow the boy to relieve himself, Jackson’s father could be hauled off to jail for gross indecency. God forbid that a White woman should drive by and see a little Black boy peeing on the side of the road.

Jackson recalled that he wet his pants in the back seat of the car.

“You know what my dad did? He pulled over and spanked me. It was a lesson that I would never forget, I had to be stoic in adversity and it made me want to become a force for good and for change. My dad always told me that Heaven never was and is not now segregated, but this world is not Heaven,” Jackson said.

Both Cowboy Mike and Jackson Parks would be the first to tell you that the greatest evil to face the modern Black community is the loss of the father figure. Jackson mentored the boys of the streets and Cowboy Mike took young Black men who made it into college under his wing.

Both men, however, understood they were the exception to the rule and could never replace a father in the home.

Ironically, during a time of repression and marginalization, the Black family unit remained largely intact.

According to the Census Bureau, data between the periods of 1960 to 2013 show that African–American children who lived in single-parent homes more than doubled from 22% to 55% ,and according to a report in The Atlantic. Today, 48% of black children are living with a single parent, according to the Institute for Family Studies.

Neither Cowboy Mike nor Jackson Parks wanted statues erected in their honor. They would want our community to come together and honor their legacies by supporting mentorship groups such as 100 Black Men of Augusta and the Augusta Boxing Club, both of which do the Lord’s work, in my opinion.

We must also support local politicians and law enforcement who are keenly aware that children must be reached before their innocence is despoiled, and we must reject the politicians who claim to be their “brother’s keeper,” but are in reality charlatans who are in the game only for their own benefit.

Scott Hudson is the Senior Investigative Reporter and Editorial Page Editor for The Augusta Press. Reach him at scott@theaugustapress.com