In an era when public education was almost non-existent, one man had a vision of the future that would have a dramatic effect on Augusta’s youth. His name was John Houghton.

In 1851, the year that Houghton died, only children of the well-to-do had much access to formal education; even then, the education was limited to early childhood and mostly taught by the child’s mother.

The Academy of Richmond County was founded in 1753, but it was available only to children of the elite.

For example, the progeny of a successful attorney, doctor or landowner would be schooled at home until they could be sent off to university or apprenticeship.

Incredibly, according to Oxford University, most people in the nascent United States were actually literate with an 89% rate among whites and 41% free Blacks. In that era, most enslaved people were not afforded any education opportunities past learning to write their names.

Some very enterprising young people, especially those seemingly trapped on the family farm, took to educating themselves by borrowing books from a local library.

In Augusta, though, the only library available was created between 1732 and 1750 using books brought over from London on the ship The Charming Nancy and donated to the newly created city. The library, according to the Richmond County Library Public System, started with only 166 tomes and patrons were charged an annual subscription fee.

The first true free public library would not be created until 1888, almost 40 years after Houghton died.

Houghton’s name first surfaced in the public record in 1849; he was an opponent of funding the expansion of the Augusta Canal through a “canal tax,” writes Ed Cashin in his book, “The Story of Augusta.”

In the Antebellum era in Augusta, Houghton, originally from Boston, was a successful leather merchant. However, he most certainly had other business interests as he is recorded as owning 51 slaves whom he freed in his will, paid for their passage to Liberia, a free colony in Africa that remains a country to this day. He also gave each freed slave a small amount of money for use when they arrived in their new land.

Not only was Houghton “somewhat” an abolitionist a decade before the Civil War, he had a vision of the future where every child, even those coming from meager backgrounds, would be guaranteed a basic education.

Houghton would die at 63, and he was remembered in his obituary in The Augusta Chronicle as a “strictly honest man, amiable and charitable, modest and retiring in habits. He left ample regard for the poor in his large legacy to be appropriated to their education.”

Other than his brief obituary, little is known about the man. He wasn’t married at the time of his death and left no known children.

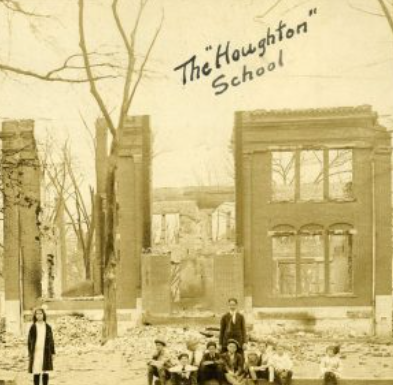

In his will, Houghton established a fund with $4,000 given to the city of Augusta, a princely sum at the time, according to Heritage Academy, as well as a small plot of land. The first public school in Augusta, the Houghton School, opened in 1853, with the building also open for religious services on Sunday, per Cashin.

Houghton directed that part of his gift was to establish a trust fund to continue free education well into the future.

It would not be until 1872 that the Richmond County Public School system would be chartered, and by that time, the Houghton School had been privately educating children of the poor for two decades.

In the 1890s, the Houghton School was incorporated into the newly chartered system as Augusta’s first public elementary school, or a “pre-school” as they were termed in those days. Its original building would become a casualty of the Great Fire of 1916, and the replacement building would carry on serving the public until 2000, when it was later sold off as surplus.

In 2007, the building would return to the hands of educators, becoming Heritage Academy. According to the Augusta Chronicle, when the “new” building was erected after the fire, Houghton’s remains were moved from their remote location on a farm and re-interred in the lobby of the school, where they remain to this day.

Not only did Houghton’s legacy live on through the establishment of public education in Augusta, his original trust fund continues on as well, so you can say that Houghton continues to pay for modern kids to be educated.

…And that is something you may not have known.

Scott Hudson is the Senior Investigative Reporter and weekly columnist for The Augusta Press. Reach him at scott@theaugustapress.com