Sometimes it takes history a little time to catch up with the full legacy of important figures of the past; former Georgia Gov. Carl Sanders is one of those figures.

Augusta would not be the city it is today without the efforts of Carl Sanders throughout his long career in politics.

On the surface, Sanders appears to be a bit of a paradox. He was a member of the Democratic party during the segregation era; yet, through his pragmatic manner and charismatic style that held wide appeal, Sanders led Georgia into the integration era by largely working in the background and doing everything possible to avoid the racial violence that was occurring in other Southern states.

When Sanders was born in 1925, the Cracker party held a tight grip on Georgia politics and racism was the rule of the day; however, growing up in Augusta with plenty of Black friends, Sanders was brought up to be compassionate and colorblind.

MORE: Augusta OKs audit of Recreation Department

Sanders wanted to become a lawyer and went to the University of Georgia on a football scholarship and briefly left when he became of age to fight in World War II, according to the New Georgia Encyclopedia.

Despite training to fly the B-17, which he dubbed the “Georgia Peach,” the war ended before Sanders could be sent overseas.

After the war, Sanders settled into a successful law practice in Augusta when he was bitten by the political bug.

In 1954, Sanders was elected to the General Assembly where he rose up in the ranks of the Democratic party at a critical time. Clever to avoid riling the then powerful Ku Klux Klan, Sanders proclaimed himself a moderate segregationist, but his actions once in elected office would show that he was firmly against segregation and racism.

According to son Carl Sanders Jr., the elder Sanders felt segregation was holding Georgia back economically and that equality among the races would spur investments in the state from international industries that tended to ignore the South because of the racial turbulence.

“He definitely walked a tight rope, especially when it came to the Civil Rights Movement. He didn’t want the heavily segregated Birmingham to become the hub of the South, he knew that if Georgia became more progressive, Atlanta would take that title, and that is exactly what happened,” Sanders Jr. said.

According to the Macon Telegraph, during Sanders’ tenure, Georgia’s population nearly tripled from 3.9 million to 9.9 million; meanwhile, Alabama only grew from 3.2 million to 4.8 million during the same time.

As a Georgia assemblyman, Sanders achieved prominence arguing against the folly of closing down schools rather than complying with Brown v. Board of Education; Sanders and his peers managed to introduce integration into the schools by simply claiming they were only following federal law.

Thanks to Sander’s later lobbying efforts as a senator, in 1961, the first Black students were admitted to his alma mater, UGA, and unlike the Little Rock Five, the students did not need an armed escort to attend class.

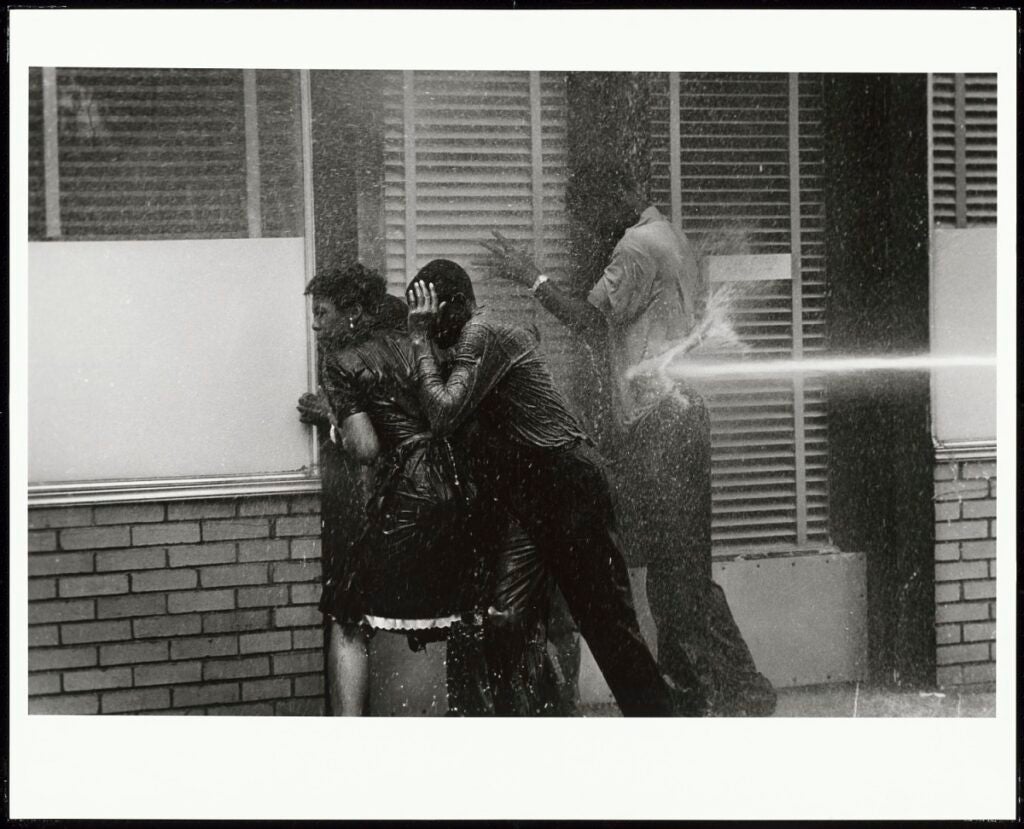

Sensing that Georgians were just as appalled as others across the nation to see the images on television and in newspapers of Black citizens being hit with high pressure fire hoses by policemen in parts of the South, Sanders, by that time a state senator, decided to run for Governor in 1962 as a modern, or New Democrat and handily beat arch-segregationist Marvin Griffin, making him Georgia’s youngest governor at age 37 years.

“This is a new Georgia. This is a new day. This is a new era,” Sanders proclaimed in his inaugural address.

One of Sanders first acts was to desegregate the Capital Building.

Rather than issue a public order or hold a press conference, according to the Atlanta Journal and Constitution, Sanders instructed the maintenance crews to remove all ‘White’ and ‘Colored’ signs from water fountains and bathrooms and had the barriers removed from the gallery that separated the races.

Assemblymen, senators and staff as well as the public walked in the Capital Building the following morning to find all the signs and barriers gone. Down in the building’s basement, the Department of Motor Vehicles was changed so that lines to obtain a vehicle tag were no longer segregated.

When the segregationists tried to feebly protest, Sanders, again, stated he was only following the law.

It is said that Alabama Gov. George Wallace of “Segregation now, segregation tomorrow, segregation forever” fame, who was sworn in the same year, requested an official meeting to set his colleague straight on the race issue. Sanders politely declined and reportedly Wallace never forgave the snub and vowed that he would prevent Sanders from ever getting elected again.

While the snub would indeed impact Sanders later, for the meantime, he focused on building the foundation for Georgia to become an economic powerhouse.

In the process, Sanders also helped transform his sleepy little hometown of Augusta into the modern metropolis that it is today. The education reforms under the Sanders’ Administration changed the two-year Junior College of Augusta to the four-year Augusta College.

Later, Sanders would lead the charge to expand the Medical College of Georgia by securing the funding to create the dental school.

Sanders also dabbled in real estate, joining forces with other local developers to create the Westlake Country Club. According to Sanders Jr., the elder Sanders foresaw the eventuality of the Masters Tournament becoming an international event and wanted Augusta to become known as the ‘Golf Capital of the World.’

“Westlake wasn’t at first the huge success he thought it would be. People didn’t want to move from The Hill to a neighborhood that, at the time, was really out in the middle of nowhere,” Sanders Jr. said.

According to Sanders Jr., the elder Sanders also saw the potential of riverfront development, but it was being stymied by the state floodplain restrictions that were in place from before the Thurmond Dam was built.

“Dad was able to get the floodplain changed and now we have developments all along the Savannah River and over in South Carolina, Hammonds Ferry and the North Augusta Greenway; those wouldn’t be here today if not for his work,” Sanders Jr. said.

Long before the efforts of the late Congressman Charlie Norwood to keep (then) Fort Gordon off the Base Relocation and Closure list (BRaC), in 1963, Sanders appealed directly to President John F. Kennedy to save the base from closing.

Sanders flew on corporate magnate J.B. Fuqua’s private plane for an Oval Office meeting with Kennedy and the result was Kennedy pulling out his pen and striking Fort Gordon from BRaC.

A year later, in the wake of the Kennedy assassination, a somber Sanders returned to the White House, this time at the behest of President Lyndon Johnson to help craft the legislation that would become the Civil Rights Act of 1964.

An avid fan of competitive sports since his youth, Sanders was instrumental in bringing the Atlanta Hawks, Atlanta Falcons and Atlanta Braves to Georgia. A member of the Augusta National, he promoted the game of golf.

Faced with term limits, Sanders had to step down as governor in 1967, but he decided to run for the office again in 1970, where he would face a somewhat unknown former senator and peanut farmer by the name of Jimmy Carter.

The Carter campaign found that it could not compete with Sanders on a platform of public policy, so the decision was made to attack the former governor for his progressive policies on race. According to press reports of the time, the still-smarting Wallace was more than eager to assist.

Carter accused Sanders of being an elitist, not being a good segregationist and pandering to the Black vote. A photo of Sanders celebrating an Atlanta Hawks basketball game victory where a Black player doused the former governor with champagne was disseminated along with language that would be supremely offensive today.

The Carter moniker of “Cufflinks Carl” was tame compared to the other epitaphs hurled at Sanders.

Incredibly, Carter’s tactics worked and the rest is history; Carter would eventually make it to the White House, and Sanders retired from politics to focus on his law practice, which would eventually swell to some 600 attorneys becoming one of the largest legal firms in the nation.

In later years, Sanders would say that he himself never had presidential ambitions and that his gubernatorial loss was really a catalyst for his achievements later in life.

“The great thing about my dad was that he was never bitter. He fought hard for his convictions, sometimes he won and sometimes he lost. What he found out was that he could get a lot more good accomplished outside of government and that is what he did,” Sanders Jr. said.

…And that is something you may not have known.

Scott Hudson is the Senior Investigative Reporter and Editorial Page Editor for The Augusta Press. Reach him at scott@theaugustapress.com