Since the dawn of recorded history, people have observed New Years as a holiday, but the way we celebrate has changed dramatically over the epochs.

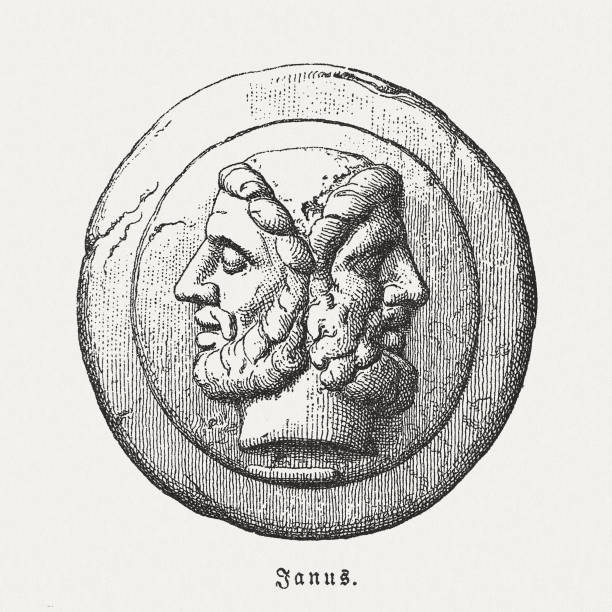

In Roman times, the Agonium, or festival of Janus, was observed in the many temples erected to the god for whom the month of January is named. Janus was the god of transitions and was depicted as having two faces, one looking to the past and one to the future.

The Romans held so many festivals throughout the year that the Agonium of Janus was actually considered a rather minor holiday.

American traditions in the 18th century that made their way to America from Mother England were Wassailing and Mumming.

On New Year’s Eve, women would carry a large communal bowl of wassail, a hot drink made of mulled cider with cinnamon and nutmeg, and in exchange, they would receive a gift.

As the night wore on, mummers would visit neighboring houses, according to Bethany Meeker writing in The Historical Homemaker, and these would be men who had already partaken in wassail and who would perform songs and skits in order to get more wassail.

Meeker writes that the tradition never really went away; it just moved holidays to Halloween where we get the phrase “trick or treat.” The treats are now candy rather than alcohol.

The Victorian Era brought about some rather strange traditions that have been somewhat forgotten.

New Years celebrations of the time were small affairs held in the home. It was considered bad luck to allow women in one’s house first on New Year’s Eve, so women had to wait out in the cold while allowing the men to enter first.

That rule would likely not go over well today.

Commonly, an assembled group would play a new year’s resolution parlor game that had participants write rather bizarre resolutions on pieces of paper that would be thrown into a hat and passed around the room.

According to online magazine Mental Floss, an 1896 book of games indicated the resolutions could be statements like, “I must stop smoking in my sleep,” and “I must walk with my right foot on the left side.”

Of course, those resolutions were no more kept than the modern resolutions we make today.

At the stroke of midnight, the revelers would sing “Auld Lang Syne,” a tradition that remains to this day.

One American tradition that lasted well over a century was the annual pilgrimage to the White House. Starting in 1801, on New Year’s Day people would line up in front of what was known at the time as “the People’s House” to be able to get a few moments of greetings from the president.

This tradition carried on until 1932 when the nation was plunged into the Great Depression. According to White House archives, in 1931, the crowd outside ‘resembled a bread line,’ and the decision was made to quietly retire the tradition.

The annual pilgrimage also likely stopped out of fear for President Herbert Hoover’s safety. America, at the time was in the wake of three presidential assassinations, and the Great Depression had created shanty-towns known as “Hoovervilles” all across the nation. According to the Library of Congress, Hoovervilles resembled the homeless camps of modern day San Francisco; only the people were not sleeping in tents, but shelters made out of cardboard boxes.

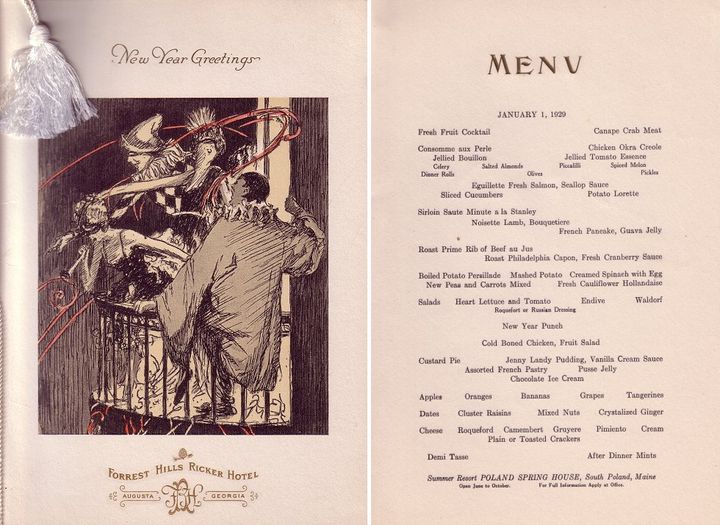

Prior to the Great Depression, in the Edwardian Age, New Years was the pinnacle party of the year.

Luxury hotels in Augusta such as the Forrest-Ricker would hold sumptuous feasts that would last for hours with course after course with dishes such as Eguillett fresh salmon with scallop sauce, roast prime rib, boned chicken fruit salad, roast Philadelphia capon and enough desserts to satisfy any sweet tooth.

What is not mentioned on the Forrest-Ricker menu is the alcohol that was served and despite prohibition, there was plenty of booze to go around.

Later, during the Depression and the war years, most people did not hold fancy parties for New Years, but rather sat around the radio, listening and hoping for good news.

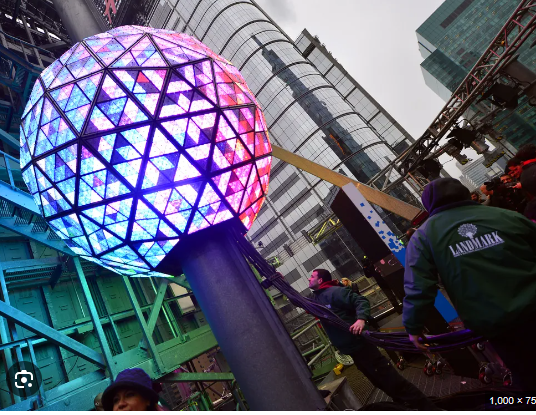

After the war, America never went back to the fancy-smancy formal dinners and New Years Eve remained a holiday largely celebrated in the home. Not only were people of the 1950s and 1960s worn out from the seemingly endless Christmas parties, but television offered a fun reason to stay home and watch the glittering ball fall at Times Square.

The Times Square ball drop began in 1907, but it became a national event with the advent of the TV set.

This tradition of turning on the tube before midnight on New Year’s Eve remains today with normally staid television news personalities getting drunk on-air with comedians. However, the so-called “hour ball” was something appropriated from England at a time when most people could not afford a pocket watch.

According to Britannica, the first hour ball was installed at the Greenwich Observatory in 1833, and it would be manually lowered each hour to let passersby know the hour and also provided the service to passing ships on the Thames, where the navigator could see the ball on shore and adjust the chronometer on the vessel.

…And that is something you may not have known.

Scott Hudson is the Senior Investigative Reporter and Editorial Page Editor for The Augusta Press. Reach him at scott@theaugustapress.com