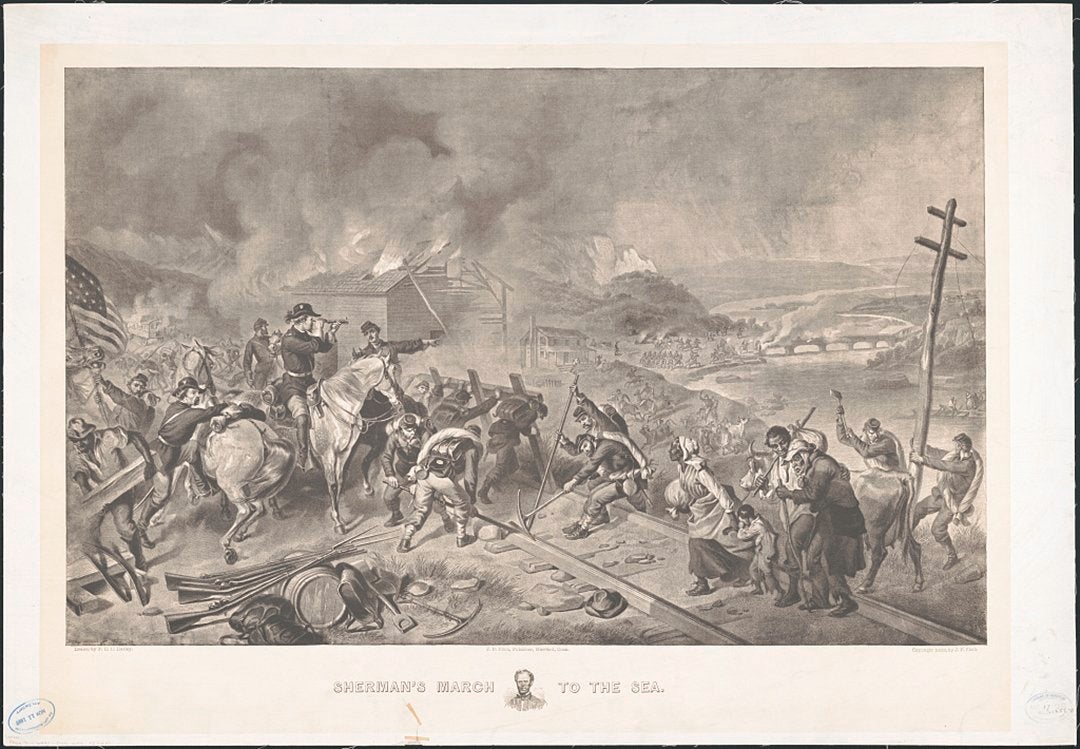

Few other military campaigns have been romanticized and demonized more than Union General William Tecumseh Sherman’s infamous “march to Savannah.”

The military campaign, which took place between Nov. 15 and Dec. 21, 1864, as the American Civil War neared its close, has spawned stories of secret girlfriends, cities deemed “too beautiful to burn” and alleged unimaginable brutality as “payback” for the institution of slavery.

Generations of Southern children were taught to believe Sherman was a man so hell-bent on revenge that he ignored the suffering Union POWs held at Andersonville in favor of burning cotton fields and freeing slaves.

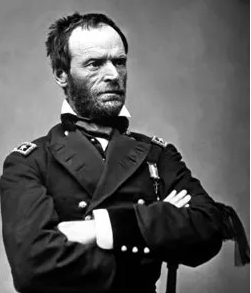

Modern historians, though, have come to view Sherman and his march through Georgia as an event not nearly as brutal as the popular imagination would make it out to have been. It was an example of total war, but suffering experienced by Southerners at the end of Sherman’s bayonet was not nearly as destructive as alleged, and it certainly saved lives in the long run by helping bring a swift conclusion to the war.

Historian David Davis, writing for the American Battlefield Trust, argues that Sherman’s march was not a situation where bandits dressed in Union uniforms cut a 50 mile-long swath of destruction, burning everything that could not be eaten; rather, the march was a meticulously timed campaign with a clear goal aimed at destroying Confederate morale.

“Certainly, Sherman practiced destructive war,” Davis writes. ”But he did not do it out of personal cruelty. Instead, he sought to end the war as quickly as possible, with the least loss of life on both sides.”

Sherman was not looking to conquer land but to break the will of the civilian population.

In reality, Sherman’s campaign did not last all winter long. In fact, it only took Sherman and his men roughly a month to travel the 285 miles across Georgia.

In terms of war logistics, Atlanta, not Augusta, had to be destroyed. Atlanta was the railroad hub through which supplies for the Confederate army in Virginia passed. Sherman knew that he could shut down the South’s ability to deliver those supplies by destroying the rail hub, he would shorten the war.

As George Washington Rains, commander of the powderworks facility in Augusta and the Augusta Arsenal during the war once said: “the South did not lose the war for want of gunpowder.” Sherman didn’t destroy the gunpowder, be destroyed the means to transport it.

According to Augusta historian Ed Cashin’s book, “The Story of Augusta,” Sherman knew the layout of Augusta well from being stationed there in the 1840s, and he knew that if he tried to take the Garden City, he would be up against a heavily defended city. Further, any kind of explosion at the power works would leave everyone within several miles of the blast dead.

So, since Atlanta was the railway hub of the state, it became a much more strategically important location. Sherman didn’t have to destroy the South’s gunpowder if he could eliminate their ability to transport it to the battlefield.

Much is made of Sherman cutting his own supply lines and having his troops forage off the many working farms in the South. The angle seems to always be that Sherman wanted to deprive Southerners of the very food they needed to survive.

However, keep in mind that Sherman did not have that far to travel and keeping the retinue of cooks as well as their wagons and supplies would seriously slow him down. Given that time was of the essence, Sherman’s troops did not stay in one place long enough to “sow the land with salt.”

Because Sherman’s troops traveled with all of their belongings on their backs, there is far less actual looting than a Confederate sympathizer would like to admit. In fact, evidence is strong that much of the destruction and thievery were the work of Confederate deserters, referred to as bummers.

That said, Sherman’s cavalry commander, who was charged with foraging food and fodder for the army, was, as they say, a wrong “in who was shipped South after his superiors in Virginia found out he was, essentially, stealing captured horses .ln that were supposed to be used to benefit the Union army.

There is a reason Sherman claimed the title of “the American father of total warfare.”

Since everything edible had already been harvested, there is no truth to the rumor that Sherman purposefully destroyed crops in the field. According to Davis, he instructed his men to take what they could fit in their haversacks, but did spare most cattle on small family farms.

To maintain secrecy, Sherman cut every telegraph line he encountered. This, of course, led to even more chaos and the rumors of brutality spread like kudzu.

Davis writes that once in Savannah, Sherman offered lenient peace terms. Some fleeing Confederate officers even left their wives and children in Sherman’s personal care. They knew him as a gentleman.

…And that is something you may not have known.

Scott Hudson is the Senior Investigative Reporter, Editorial Page Editor and weekly columnist for The Augusta Press. Reach him at scott@theaugustapress.com