In the heart of downtown Augusta sits an unassuming building that is actually a national historic treasure: Springfield Baptist Church.

While there is some disagreement on which is the oldest Black congregation in the United States, there is no doubt that Springfield is one of the oldest, predating the U.S. Constitution.

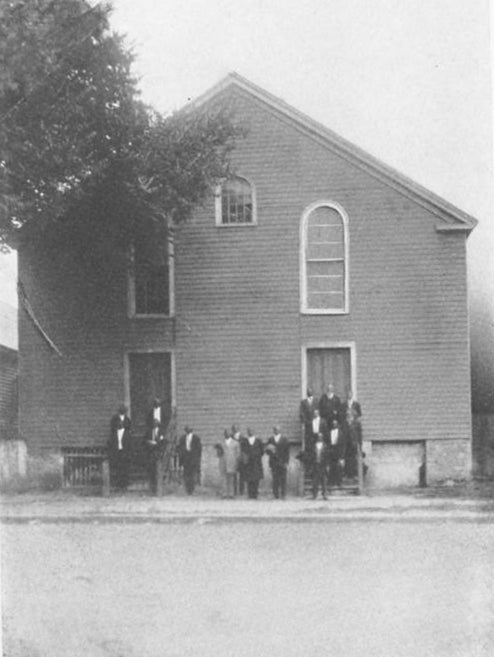

The marker in front of the church, located at 114 12th St., states that Springfield is the oldest independent African American church in the nation. When the church became officially affiliated with the Baptist denomination is unclear; however, the church’s first minister, Jesse Peters, had ties to the Silver Bluff Baptist Church, which was founded by slaves in 1774 in Beech Island, S.C.

Founded in 1787, the church was somewhat of an anomaly in the Deep South as it was founded and attended by free Black men and their families. At that time, it was possible, if not ordinary, for people of color to eventually purchase their freedom.

According to the late Augusta historian Ed Cashin in his book “The Story of Augusta,” most of the early parishioners at Springfield were rivermen. These were highly skilled pilots who poled the shallow Petersburg boats upriver to pick up tobacco, cotton and other staples and brought the goods back to the port of Augusta.

“Before the advent of steam powered boats in 1817, Augusta trade was fueled by the energy of the rivermen,” Cashin wrote.

Considering that the men were vital to Augusta’s economy, Cashin writes that hardly anyone blinked an eye when the members of Springfield Baptist bought the original clapboard building from the Augusta Methodist Society in 1801 and had the building moved to its current location.

The atmosphere would change in 1818, according to Cashin, when Augusta councilmen passed an act that required Springfield parishioners to register their names and occupations with the City Clerk’s office. From those records, it is learned that most of the men of Springfield were skilled laborers with blacksmiths, saddle-ostlers and millwrights identified.

Meanwhile, the women listed themselves as weavers, housekeepers and quilters. The quilts made in Springfield at the time were legendary for their beauty and workmanship.

Another interesting fact in the City Clerk’s registry that may be a bit painful for some to digest today was that, in 1818, a total of 25 Springfield Villagers owned slaves themselves, according to Cashin, and 12 of those slave owners were women.

An interesting side note is that the current brick building, which was built around a clapboard structure, does not look like most Southern churches of the era. The architecture resembles more of a New England church house, showing that those who built the brick portion of the church were were aware of architectural styles from other parts of the country.

According to Peter Benes, writing in the University of Massachusetts Press, Northern church houses, commonly called “meeting houses,” lacked the columns, elaborate stained glass and thin spires, but rather were plain in appearance and had a simple bell tower.

“Inside they resembled an oversized, well-lighted, one-room schoolhouse with poor acoustics,” Benes wrote.

Religion and slavery became a troubling mixture for slave owners; however, slavers and pastors managed to twist the Holy Bible around to justify Black bondage.

Ministers argued that Blacks brought in from Africa were essentially savages and that God ordained slavery so that the captured slaves could learn of Christ and be saved from the wages of sin.

Woodrow Wilson’s father, Joseph Ruggles Wilson, a Presbyterian pastor, famously repeated in 1861 what had been preached for decades and used the book of Ephesians to justify slavery.

“It points out a dependent who is solely under the authority of a master: that master being the head of a household and wielding over his slaves the commission of a despot, whose acts are to be determined only by the restraining laws of Christianity and by general considerations of his own and their welfare: a despot responsible to God, a good conscience, and the well-being of society,” Wilson said from the pulpit.

Black churches for slaves usually were sternly controlled by the white masters. Knowing that literacy could damage the institution of slavery, the owners preferred to bring in ministers of their choice, which, according to the Pew Research Center, led to secret congregations to form where the Israelites freedom from Egyptian slavery became a constant theme.

In Augusta though, the parishioners of Springfield openly practiced their Baptist faith. Eventually, this would lead to a fracture within the Baptist Church itself.

According to the Association of Religious Data Archives, White Baptists in the South appealed to the Baptist Triennial Convention, headquartered in the North, for missionary funds as an “avowal that slaveholders are eligible, and entitled, equally with non-slaveholders.”

Those White Baptists were not happy with the convention’s response that it would not “imply approbation of slavery.” In 1845, disgruntled Baptists would meet at First Baptist Church of Augusta, mere blocks away from Springfield, and form the Southern Baptist Convention.

The fracture of the Baptist denomination only served to embolden Black churches such as Springfield, which by then, advocated the abolition of slavery; evidence has emerged in the past several decades that Springfield Baptist not only supported the Underground Railroad but used the construction of the Augusta Canal as means to hide runaway slaves in plain sight.

The so-called president of the Underground Railroad, Levi Coffin, visited Augusta at Springfield Village and distributed shoes and clothing to the newly freed slaves after the Civil War, according to Cashin.

After that war, parishioners at Springfield redoubled their efforts to help African Americans shake off the memory of slavery and become productive members of a free society.

In 1867, college courses began being taught in the basement of Springfield Baptist and this became the founding of Morehouse College, now located in Atlanta. The historic Black college counts both Martin Luther King Jr. and filmmaker Spike Lee as alumni.

…And that is something you may not have known!

Scott Hudson is the Senior Investigative Reporter and Editorial Page Editor for The Augusta Press. Reach him at scott@theaugustapress.com