In April 1861, any hope that the United States and the newly formed Confederate States of America could peacefully coexist was shattered, when Confederate forces bombarded Fort Sumter in Charleston Harbor, creating a major problem for Confederate President Jefferson Davis.

The South had plenty of men and farm boys willing to fight, but gunpowder in the agrarian South was scarce.

According to Kathleen Logothetis Thompson writing for “Civil Discourse,” a Civil War blog, Davis’ problem would ultimately change Augusta’s skyline forever, put the city at risk of being virtually annihilated and put into practice the first true assembly line in North America.

At the onset of the war, there were only a handful of factories in the South that produced gunpowder, such as the Sycamore Mill, located near Nashville, Tenn., which had a capacity of just 1,500 pounds of saltpeter, a necessary ingredient of gunpowder, production a day.

Without gunpowder, there was no way for the Confederacy to fight a war against the already industrialized North.

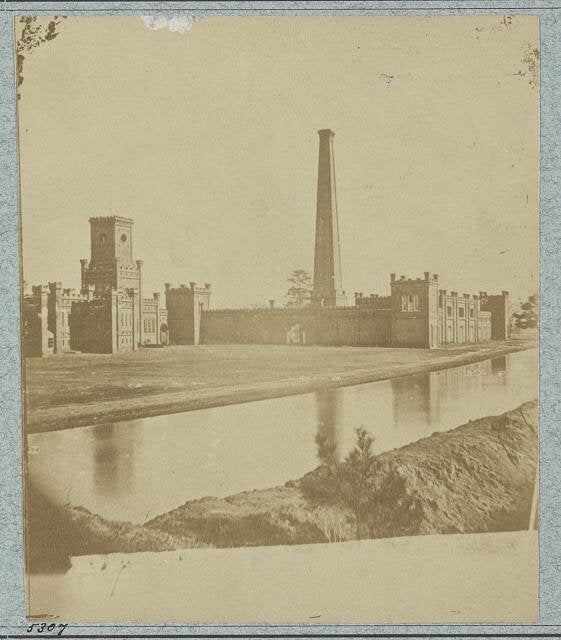

Davis tasked Col. George Washington Rains with finding a location for a massive new gunpowder manufacturing plant, and Rains did not have to go far to find the perfect location in Augusta.

The city was far enough away from any potential conflict zone, and it was already a railroad hub in the South, so powder could be produced without the fear of invasion or sabotage and could be shipped by rail to many points in the Confederacy.

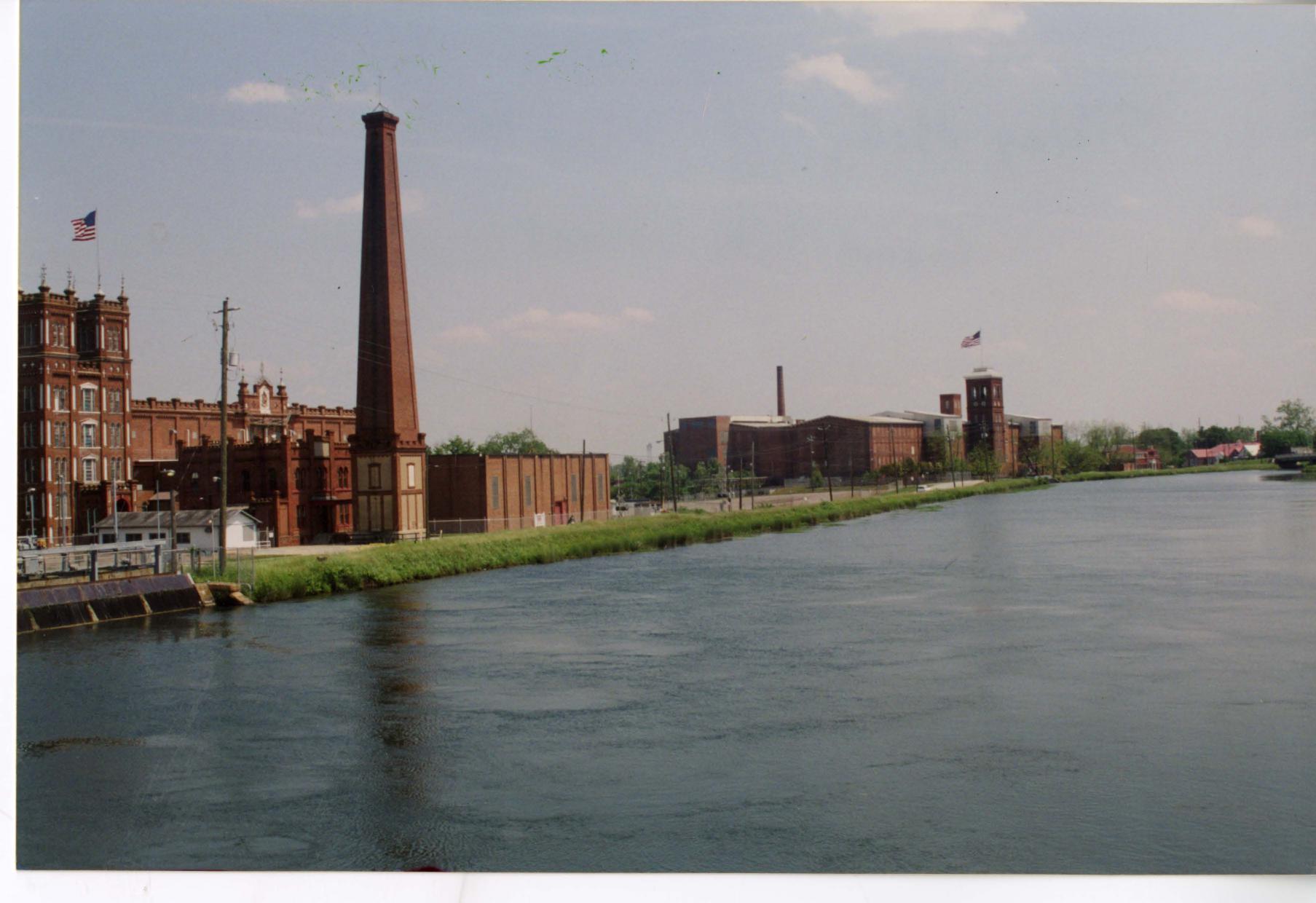

The most important factor, though, was, unlike other Southern cities, Augusta had long before industrialized with the creation of the Augusta Canal in 1845. All along the canal were factories that produced textiles such as cotton and silk as well as other goods.

William Goodrich was one of those who owned a massive facility that made windows, doors and sashes, and the road out in front of what was once the Confederate Powderworks is still named in his honor.

Records of the time are unclear, but they do show that some of the land that became the Confederate Powder Works was part of the original U.S. Arsenal, and so that land was taken by the Confederates. However, the cash-strapped Confederate government likely paid for other land and existing buildings using war bonds, meaning that by the end of the war, the prior owners would have been left with nothing but a briefcase full of worthless paper.

Rains set about building the 28-structure complex using blueprints of a factory from London, but Rains also changed the blueprints dramatically to fit his idea of raw materials entering one end of the factory complex and the finished product coming out of the other end.

Mainly to safely work with the volatile materials, Rains created what is considered to be the earliest use of an assembly line, long before Henry Ford refined the process to build the Model T, according to the Georgia Historical Society.

Early records also leave historians stumped over who exactly worked at the complex and whether slaves were brought in to manufacture the very product that could keep them in bondage.

Records of the time indicate the workforce was about 50-50 White and Black, but whether those Black men were enslaved or free is not precisely known. According to Thompson, as the tide of the war changed in favor of the North, more and more slaves might have been used as White men were conscripted into service to the army. However, there is no solid evidence this ever happened.

One reason enslaved persons would have been a poor choice for labor was the risk of sabotage; so, if slaves were used, they were likely used for menial labor that kept them away from the manufacturing process and storage magazines.

While there were no known attempts at sabotage, the powder works were still a very dangerous place to work, and at least five explosions occurred in the three years it operated. According to Thompson, most of those explosions were minor with the exception of one that occurred in 1864.

Records show that a worker waited until the supervisor was not around to light up a cigarette, and his discarded match ignited a magazine killing eight men and a boy.

As the war began to wind down, Augusta’s biggest asset became its biggest potential liability as General Sherman began his famous March to the Sea.

As Sherman’s army neared, the inhabitants of Augusta prepared for a siege, knowing that if the powderworks were attacked and blown up, the city would go up with it.

Breastworks were created all along Raes Creek and even the walls of Magnolia Cemetery were commandeered for defense of the city. However, Sherman had other ideas.

By the time of Sherman’s march, Augusta was largely a hospital city, and while the Confederate Powder Works might have seemed like a strategic target, Sherman knew that the powder works had been sidelined already. The Confederates could make all the gunpowder they wanted, but they no longer had the ability to ship the product out of the city.

In fact, the situation had become so dire for the Confederacy that Southern churches were turning in the bells from their spires to be melted down into artillery, according to the late Augusta historian, Ed Cashin, in his book, “The Story of Augusta.”

No, Sherman did not have a girlfriend in Augusta that pleaded with him to spare the city. He just did not want to fight a bloody battle to take over a city filled with wounded soldiers and starving refugees all to stop gunpowder production when it would never reach a battlefield anyway.

During the war, the Confederate Powder Works produced 2,750,000 pounds of powder, leading Rains to proclaim that the South did not lose the war for want of gunpowder.

The only thing left of the Confederate Powder Works, which was the only building built by the Confederacy, is the giant brick chimney in front of Sibley Mill that can be seen from Riverwatch Parkway.

…And that is something you may not have known.

Scott Hudson is the Senior Investigative Reporter and Editorial Page Editor for The Augusta Press. Reach him at scott@theaugustapress.com