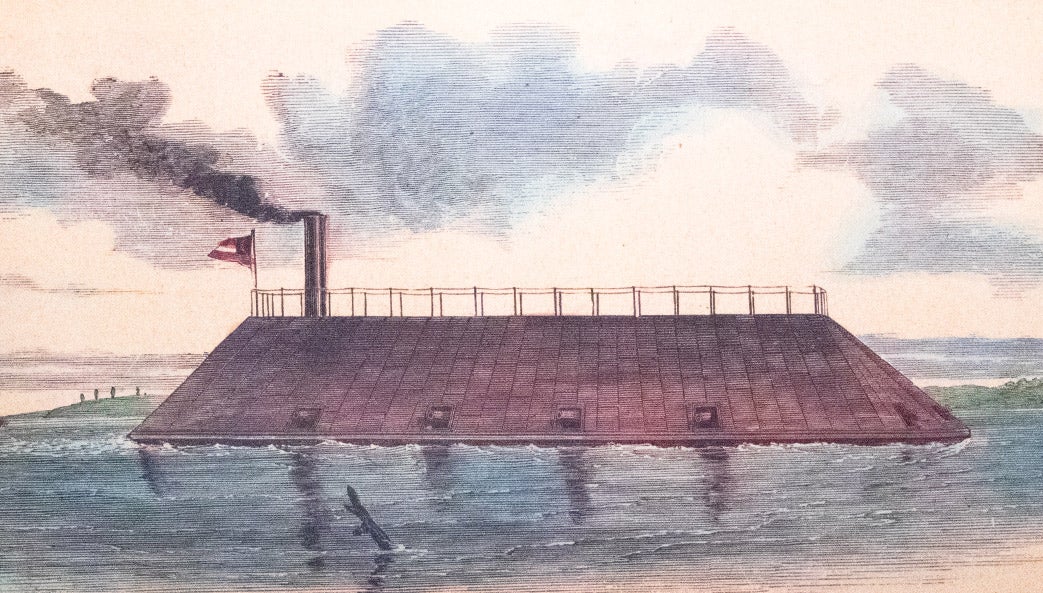

Every school kid learns of the epic battle between two of the world’s first ironclad ships, the CSS Merrimack (Virginia) and the USS Monitor, but other history-making ironclads, such as the CSS Georgia have been lost in the dustbin of history.

The naval showdown that happened at Hampton Roads, Va. in March of 1862 did not produce a clear winner, but, in hearing that onlookers reported that the cannonballs from both sides tended to bounce off the enemy’s iron skin, causing no damage, the Confederates believed they had an answer to a major problem.

After the politicians’ fiery orations ended and the parades celebrating secession disbanded, it became very obvious to Southerners they were in a disadvantaged position in a very real war. While the North’s industrialization combined with vast natural resources made them very much self-sufficient, this was not the case in the South.

The Confederates not only needed to export their cotton and tobacco to keep the financial coffers filled, according to the National Civil War Museum, they also relied on imports to live.

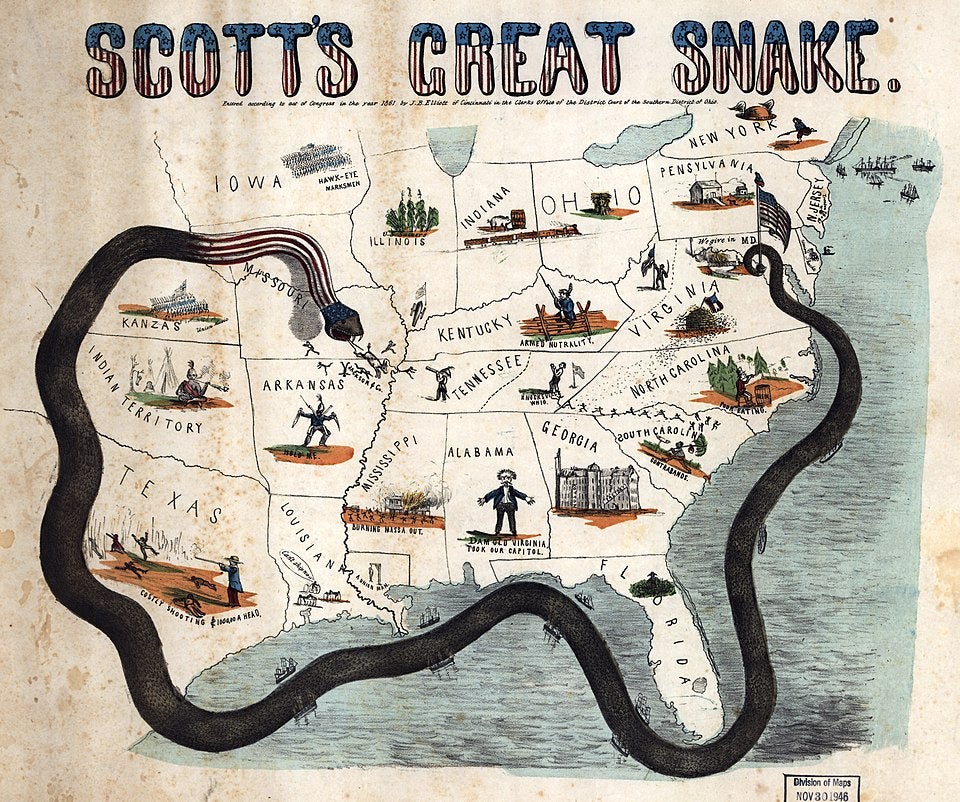

Union General Winfield Scott devised a plan that he claimed would choke off the Confederacy and put a quick end to the war. President Abraham Lincoln immediately approved of the “Anaconda Plan,” a blockade meant to slowly squeeze the South into submission.

According to the American Battlefield Trust, in some ports, the Confederates were able to use small, swift boats to outrun the blockades, and cities such as Charleston, S.C. and Wilmington, N.C. had massive fortifications that did a good job of repelling the blockaders, keeping them far out to sea. Some ports reported being 90% effective against the blockades, but never-the-less, they were effective in dousing the South’s morale.

While the so-called Anaconda Plan did not bring a quick close to the war, it did seriously disrupt both civilian and military life by depriving the South of something that was, at that time, vital for survival: salt.

In his video series, “History to be Remembered,” historian Lance Geiger recounts why salt was so important to 19th century life. Unlike today, when a container of salt may sit hardly used in the seasoning rack for years, it was once really the only way to preserve most foods unless one lived near a lake that froze over in the winter and had a means to store ice.

The Florida Division of Historic Resources lists the weekly rations of the typical soldier as a pound of meat such as pork or bacon along with dried peas, rice, coffee and salt.

The Anaconda Plan did deprive the South of that vital resource.

According to Geiger, letters and other documents survive detailing how some families would have to wait before slaughtering their pigs because to do so would mean that around half of the meat the animal produced would rot before it could be consumed.

Not only did the price of salt skyrocket, but women complained that they had to dig up their smokehouse floors to soak them in water and boil the water down to retrieve a few dregs of salt. The scarcity of the resource made quality of life miserable and caused some to question whether the war was winnable.

After hearing about the Battle at Hampton Roads, the Confederates felt they might have an answer to the blockade, especially in places such as Savannah which lacked enough fortifications to cover the entire harbor. What they needed was an ironclad that could, instead of sailing around the Union warships, blow them to smithereens and open the port up completely.

Women in Savannah immediately took up the cause and formed the Ladies Gunboat Association to raise the funding needed to build such a boat. In Augusta, according to news reports in the Augusta Chronicle, Sophia Schley, the widow of former Governor William Schley, created the Augusta Chapter called the Ladies’ Volunteer Association, and the reports paint the picture of a woman dedicated to her cause.

There are no longer any records showing just how much was raised in Augusta, but according to the news reports at the time, the effort locally was a success, and the Savannah ladies group ended up raising all of the $115,000 needed to build the vessel.

What was not considered a success, at least not at first, was the prototype that emerged, the CSS Georgia.

According to the publication, “Emerging Civil War,” local businessman Alvin N. Miller was chosen to design the vessel, but he ran into problems immediately due to a shortage of the needed iron. Consequently, the ship evolved into a hybrid, with a wooden keel and wood under the waterline and iron that was recycled from locomotive rails acting as the “iron cladding.”

The result was a ship so heavy that its boilers could not produce enough power to sail against the tide and it would barely move at neap tide. While ironclads were not meant to be swift boats, the CSS Georgia was so underpowered that there was no way it could ever be effective at battling the blockaders.

The Confederates tried anchoring the vessel in position to act as cover for the quick blockade runners, but its firepower was not sufficient enough to repel the Union vessels from such a distance.

The CSS Georgia also leaked so badly that the bilge pumps couldn’t keep up, forcing the men to use buckets to continually bail out the water as it poured in from virtually every seam.

However, the worst part for the sailors was that to simply keep the bilge pumps running, the boilers had to be lit at all times. The heat coming off of the boilers along with the hot Georgia sun beaming down on the railroad tie armor caused the boat to be scalding hot to the touch.

Finally, the Confederates gave up and decided to find a place to scuttle the Georgia where the gun turrets would remain above water, making it a sunken platform to repel Union attacks. Surprisingly, this idea worked. In fact, according to the American Battlefield Trust, it worked so well that Miller insisted and even bragged that it was his plan for the vessel all along.

The CSS Georgia may have been a failure as battleship, but it was a success in defending the harbor from attack.

It was a success, that is, until one “Uncle Billy” Sherman arrived from the opposite direction some years later.

…And that is something you may not have known.

Scott Hudson is the Senior Investigative Reporter, Editorial Page Editor and weekly columnist for The Augusta Press. Reach him at scott@theaugustapress.com