If you find yourself on one of the many coastal islands from North Carolina to Florida, you might think you have been transported to another country, to the land of the Gullah Geechee.

Technically, the Gullah Geechee Cultural Heritage Corridor runs from Pender County, North Carolina all the way down to St. John’s County, Florida.

The federal Gullah Geechee Cultural Heritage Corridor Commission was established to govern the corridor after it was designated a Heritage Area by an act of Congress in 2006 through the National Heritage Areas Act of 2006.

So, technically speaking, the land of the Gullah Geechee is its own true “African American” nation.

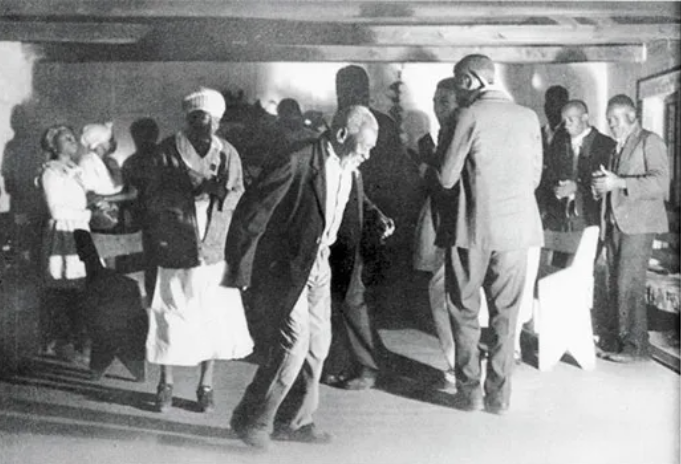

One thing that obviously sets the Gullah Geechee apart is their clothing, which makes use of bold patterns and bright colors. These are reminiscent of the ancestral clothing of West African natives, which is from where this unique culture sprang. Unlike some of the “Afrocentric” clothing sold on retail as knockoffs, Gullah Geechee fashion designs are without the overt political leanings, slogans or imagery and is specifically absent any of the popular “Black Power” motifs.

The Gullah Geechee make use of bright colors in seemingly non-reoccurring combinations the “artistic code” of which has been passed down since before slavery altered the African native’s lives. The ancient African art of dye-making once seeped down generations and made down it into the bloodlines of a transplanted people who forged on making by the use of the color possibilities they had in North America, where they were bound by slavery.

Later, as free men and women, the Gullah Geechee continue to pass down traditions, culture and, most importantly, the language, keeping the culture very much alive.

In Gullah Geechee clothing fashion, specific colors or patterns are often considered to reflect variations of the wearer’s social aspects, such as marital status or social rank, according to The Gullah Society.

A famous mid-nineteenth century actress turned abolitionist writer, after she married an American slave owner, Fanny Kemble, described in detail the clothing that Gullah Geechee slaves on St. Simon’s and Butler’s islands would wear on their days off from work.

In her book, “Ten Years on a Georgia Plantation After the War,” Kemble described the bright clothing worn by the former slaves as celebrating both their inherited African culture as well as individualism at the same time.

“They love anything shiny, valuable or not, and shells or homemade adornments are commonplace, even for the men,” Kemble wrote.

Even though the U.S. Navy disavows that Gullah Geechee culture had anything to do with the “dazzle paint” schemes used on warships during World War I, it is clear that artist Norman Wilkinson was at least familiar with it in his artistic concepts as his designs that once graced the livery of the mighty RMS Olympic and other commissioned Allied warships, pointed closely to like a nod to ancient West African art.

Wilkerson’s dazzle paint designs on warships had that same similar devotion to achieving a balance of contrasts on the canvas, like making an opera using both perfect pitch and discord and creating both a background and foreground effect that combine to rob a predator of any sense of direction.

The Gullah Geechee inspired art of today has that same hypnotic, yet almost random and ethereal quality; the baskets combine what came from Africa with was learned from native Cherokee and Creeks during their encounters. Imagine differing ethic groups, instead of robbing and pillaging, getting together to trade notes on the fine art of basket weaving and quilting.

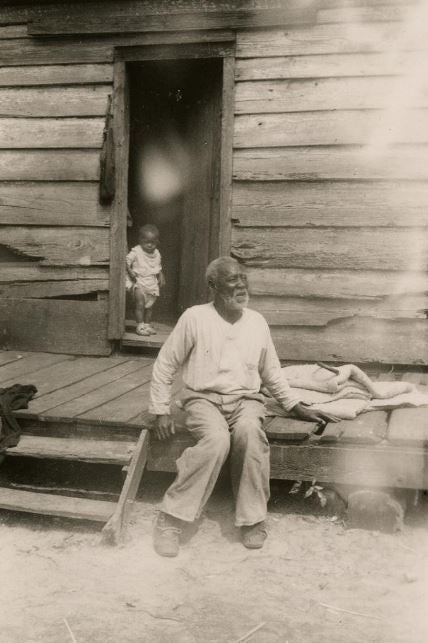

Unlike the inland populations on cotton plantations, which were rather densely populated with the enslaved and their masters living close by one another, slaves on coastal plantations had a lot more room to roam about and a lot more autonomy.

Because they didn’t live anywhere within the ear-shot of their technical masters, no one really paid attention as they crafted their own language, created a capitalistic “trade” of their homemade goods and began making their own rules.

The Gulah Geechees can be compared more with the High Middle Age peasants of Europe, people who were not necessarily free, but largely rulers of what they called home. As long as the plantations remained profitable, everyone was mostly pleased with the arrangements, including the Gullah Geechee.

During that era, Blacks were a majority (by head count) in South Carolina, but the Gullah Geechee’s never formed any kind of real rebellion, unless you learn about the antics and strange life of the legendary Gullah Jack.

In fact, the Gullah Geechee of the Low Country living today are the descendants of the last people to speak any of the West African Creole languages in North America.

Unlike any other form of “slang” dialect, the “Geechee” language is recognized by Yale University and expert linguists as an “English-based Creole” language.

“Creoles arise in the context of trade, colonialism, and slavery when people of diverse backgrounds are thrown together and must forge a common means of communication,” explains Joseph Opala, writing for Yale University.

The fact that the Gullah Geechee people lived mostly apart from their masters geographically certainly gave them more freedom. But the former West Africans’ descendants were also as precisely skilled at growing rice and indigo as were their forebearers. Despite the fact that indigo and rice are usually a very much more labor intensive crop than cotton, the cultivation methods passed from father to son meant they did not have to work as many hours to produce satisfactory results, unlike the days spent as a slave that picked cotton, even after the invention of the Cotton Gin.

Unlike their inland counterparts, the Gullah Geechee had a lot more free time on their hands, and it appears that they used that free time wisely.

The Gullah Geechee learned to craft beautiful sweetweed baskets, which are considered works of art today. The dazzling patterns also translated over to quilt making, and Gullah Geechee quilts are still prized for their beauty and quality.

In the time of slavery, it is said that the Gullah Geechee slave manufactured quilts contained maps to “safe” points north for those travelling the Underground Railroad. Ironically, it was enslaved people, who had no use for freedom due to the ease of their lives, who made quilts for those desperately wanting to escape bondage.

Unlike other slave populations, after the Civil War, most former slaves never left the Sea Island plantations, but instead, they acclimated themselves to being free people who were still committed to carrying on and honoring their cultural heritage, which remains on display today on the coast of the Deep South.

…And that is something you may not have known.

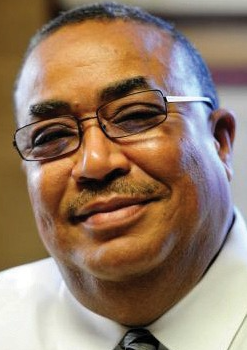

Scott Hudson is the Senior Investigative Reporter, Editorial Page Editor and weekly columnist for The Augusta Press. Reach him at scott@theaugustapress.com