No trip to Charleston, S.C. is complete without a visit to the famous, and infamous, Fort Moultrie, which, while decommissioned today, stood guarding the South Carolina coast for 171 years.

Built in 1776, the fort was hastily constructed on Sullivan’s Island using palmetto trees and sand, and it was surprisingly effective against the British forces when they attacked on June 28 of that same year, a week before the signing of the Declaration of Independence. That battle was the first victory of the Revolutionary War, and the use of palmetto trees for fort construction is why the South Carolina flag is emblazoned with a palmetto tree.

After a nine-hour naval onslaught from British naval forces, the 400 men operating the fort’s heavy cannons finally repelled the 270-gun armada, saving Charleston Harbor from occupation. The fort’s commander, Col. William Moultrie, acted with such bravery that the fort was named in his honor, according to the American Battlefield Trust.

However, the fort’s best-known claim to fame would come in the 1860s and was a part of what most historians regard as one of the darkest moments in the nation’s history.

MORE: Funeral route for Deputy Sikes announced

In the late 1850s, bickering between the states over slavery and tariffs would go from bellicose and violent — a senator had been beaten senseless by a congressman on the senate floor, after all — to an intensely bloody war with the ascension of Abraham Lincoln to the White House and 11 states by seceding from the Union.

The nation, which declared independence only 84 years earlier, fractured and the Civil War began on April 12, 1861 with shots fired on Fort Sumter from all around Charleston Harbor, including Fort Moultrie.

According to the American Battlefield Trust, Fort Sumter was one of the few federal installations not surrendered to the Confederacy when secession occurred. The fort was built as sort of an auxiliary battle station and was no match for Moultrie’s cannons.

Ironically, no one died in the bombardment; however, the Confederates allowed the Union soldiers to fire a 100 gun salute before they evacuated, and one of the cannons exploded killing one and injuring another.

Union Maj. Robert Anderson found himself out of ammunition and totally outnumbered. He surrendered Fort Sumter to Brig. Gen. P.G.T Beauregard’s Confederate forces. Anderson’s men sailed out of Charleston Harbor bound for New York with their nation at war for the first time since the War of 1812.

The Battle of Fort Sumter would give Fort Moultrie its own chapter in the “Book of Infamy,” as more than 620,000 Americans died in the conflict, making it still America’s costliest war.

Fort Moultrie garnered another distinction during the Civil War as the site from which the first successful submarine attack was launched. The CSS H.L. Hunley set sail from Fort Moultrie under the cover of darkness intent on sinking the USS Housatonic, which was part of the blockade of Charleston Harbor.

According to the conservation group Friends of the Hunley, the eight-man crew headed out into the harbor with a forerunner of the torpedo, in the form of a spar with attached ordinance, with orders to sink the ship.

All that Union officers aboard the Housatonic might have seen before their ship exploded would have been air bubbles from the new invention as it drew close.

After being lost at sea for 131 years, the H.L. Hunley was discovered, raised and partially restored. Archeologists with the Friends of the Hunley believe that shockwaves from the bomb damaged the Hunley as well, causing it to sink, losing all hands.

By the 1880s, cannons were “rifled,” that is, grooves were etched inside the barrel which caused the bullet or ball to spin, making it travel further with a higher velocity and increased lethality. This innovation could have spelled doom for Fort Moultrie, because brick fortifications were no match for rifle-shot ammunition, but somehow Fort Moultrie survived.

In fact, the fort not only survived, but in the 1870s, it was modernized and enlarged. Larger, rifled cannon were installed, magazines and bombproofs were built using thick concrete and then buried under tons of earth giving the fort the ability to withstand the modern ammo of the times.

In 1885, several new batteries of concrete and steel, outfitted with state of the art weaponry, were constructed, transforming the installation into the Fort Moultrie Military Reservation, which, at that point, took up most of Sullivan’s Island..

Looking at the fort today, the ramparts look like they might be able to absorb anything short of a “bunker buster” bomb.

By the early 20th century, warfare had again changed with mechanized tanks replacing the calvary, machine guns that could cut down an entire battalion in moments and airplanes raining death from the skies.

Certainly by that time, a permanent fortress would have been as useful as a mott and bailey castle, made of wood, would have been in the 16th century, save but for one thing: the submarine.

The sinking of the RMS Lusitania may not have caused America to enter World War I directly, but it did give military strategists pause, as the great ship was only 10 miles, within sight of, the Old Head at Kinsale, Ireland, when she was torpedoed by a German U-boat. The tragedy killed roughly 1,200 people, 128 of them Americans.

Having a U-boat loose near a port as busy as Charleston became a serious concern of national security for military planners who decided to transform the world’s first submarine base to a submarine hunting base.

Before the advent of sonar, submarine hunting was largely done with the naked eye and multiple submarines were detected and chased off. According to the U.S. Navy’s official records, one submarine detected by staff at the fort was the German U-boat U-352, which the Coast Guard cutter Icarus sank in May of 1942.

By 1947, the world of war had jet airplanes with precision bombs, massive, city-sized aircraft carriers and, of course, the nuclear bomb which finally brought the curtain down on Fort Moultrie. The fort served the nation for almost two centuries before it was finally decommissioned and began its new life as a museum and learning center.

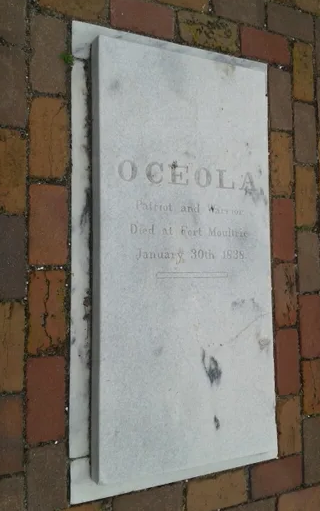

There is a grave just outside the main gates of the fort. The man buried there is Seminole Nation Chief Osceola, who gained fame by leading his native warriors fighting against the federal occupation of Florida during the Second Seminole War.

Osceola was captured in St. Augustine in 1837 and imprisoned at Fort Moultrie.

Rather than being treated as an insurgent, Osceola was treated more like a rock star, with people travelling to Fort Moultrie to pose in pictures with a “real-live Indian chief.”

After only a few months of detention, the chief became ill and died from “quincy.” After his death, the attending Army doctor removed Osceola’s head to further examine it and from there, the head disappeared, leading to legend.

Some say that Osceola’s headless ghost can be seen at times, wandering the fort at night, in search of his missing head.

…And that is something you may not have known.

Scott Hudson is the Senior Investigative Reporter, Editorial Page Editor and weekly columnist for The Augusta Press. Reach him at scott@theaugustapress.com