Without men like Elijah Clark, at Christmas, National Lampoon’s Aunt Bethany would have recited a pledge of allegiance to the Union Jack and sung “God Save The King” instead of “The Star Spangled Banner.”

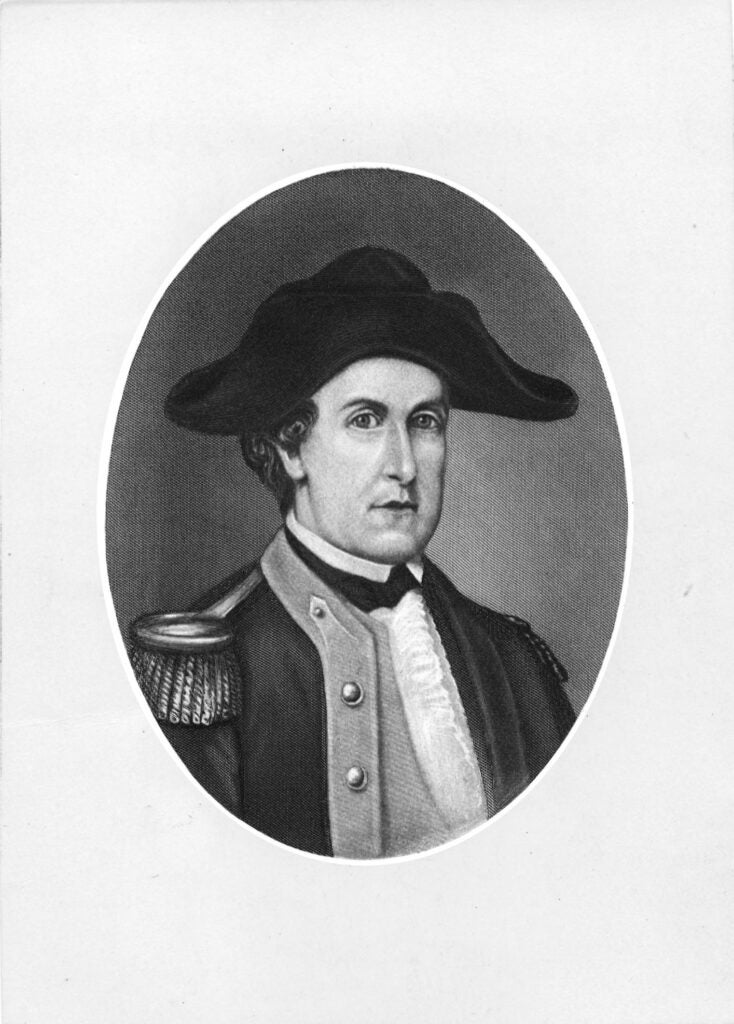

Clark fought hard to wrestle the CSRA from the British loyalists but later died shamed and penniless.

Many historians agree that the battle for the South, and specifically, the First Battle of Augusta, led to another Southern battle that was the turning point in the Revolutionary War. This eventually led the colonists to victory at Yorktown.

Clark was a brilliant tactician who even used retreat as a winning battle tactic, but he was a late comer to the parties advocating independence from England.

As late as 1774, Clark remained a staunch Loyalist and signed a document, along with other prominent Augustans, that proclaimed: “We declare our dissent to all resolutions by which His Majesty by which his favor and protection might be forfeited.”

According to the late Augusta historian Ed Cashin, writing in his book, “The Story of Augusta,” the tiny frontier town was fiercely loyal to the crown.

For reasons lost to the historical record, Clark changed his mind and joined the independence movement. Once the fighting actually started, Clark distinguished himself by conducting guerilla raids against the British and their Native American allies.

Clark was wounded several times, but never quit the battlefield.

According to Cashin, by 1779, Augusta was a divided town. Since proclaiming independence, Georgia had a constitution and an elected governor, but the British still controlled Augusta under the leadership of Lt. Col. Archibald Campbell.

However, Cambell did not last long, being forced to evacuate when a Continental Army unit of Whigs, led by General John Ashe stormed Augusta and took the town back by force.

The zig-zag of Augusta loyalties would swing again when the Southern colonies came back under British control mere months later. This time though, the British did not send Red Coats to Augusta but rather a force of Native Americans led by the infamous Loyalist Lt. Col. Thomas Brown.

Brown was a man with a hatred in his heart for his fellow Augustans.

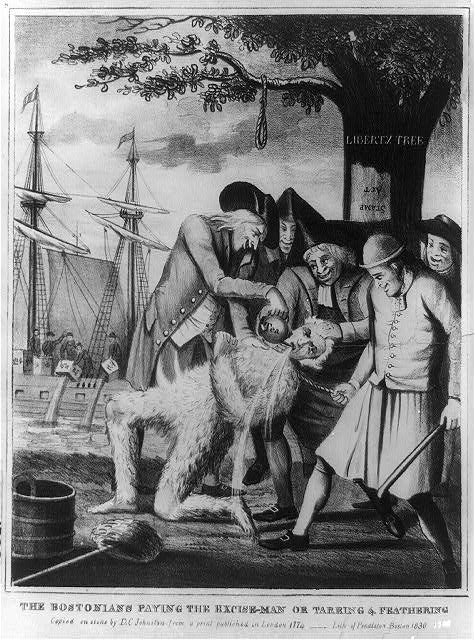

A native of England, Brown immigrated to Georgia in his early twenties and started a very successful plantation in what is now Columbia County. According to the Daughters of the American Revolution (DAR), Brown had only lived at his plantation for a year when Patriots came calling demanding that he renounce his loyalty to the king.

Brown refused, and he was beaten, burned and partially scalped before being tarred and feathered. The DAR reports that Brown lost two toes in the torture and suffered a skull fracture that gave him migraine headaches for the rest of his life.

Needless-to-say, Brown took glee in taking over Augusta and ruled with an iron fist. According to Cashin, even though Augusta was still filled with Loyalists, the population lived in fear of the man and his Native American posse.

Brown picked out the nicest home in town for his lodging, the Mackey House, the site of which the historic Ezekiel Harris house on Broad Street sits today.

Clark and his men pursued Brown, and on Sept. 14, 1780, they laid siege. Running out of food, Brown and his men tried a final strategy and raised a flag of truce to give everyone time to bury their dead. However, according to Cashin, Brown knew that the flag was far enough away that it would easily be mistaken for a flag of surrender.

As Clark and his men approached to accept surrender, at the last moment, just as Brown’s men attacked in hand-to-hand combat, Clark sensed an ambush and ordered retreat, leaving behind only 13 men captured.

Brown immediately had the men hanged, and it has long been the legend that the men were hanged from the stairwell of the Mackey House, and that Brown hung one man for each colony.

In reality, Brown hanged every man he caught, and he only caught 13 Patriots.

The retreat would allow Clarks men to fall back and participate in the battle of Kings Mountain, of which Thomas Jefferson wrote “turned the tide of success.”

Interestingly, Brown was never prosecuted for the murders of the 13 Patriots, but like Clark, he would eventually die penniless.

Clark’s success would be short-lived after the war. As a legislator, he got involved with several schemes including the nation’s first real political scandal, the Yazoo Land Fraud Affair.

Early post-Colonial Georgia extended all the way to the Mississippi River. According to the New Georgia Encyclopedia, the federal government wanted to take over the land, so Clark and his allies tried to sell the land to four different companies; of course, the deal would land the politicians a nice little sum.

When the fraud was exposed, Clark switched tactics and declared the west frontier of Georgia the “Trans-Oconee Republic.” He even sent in militias to wrestle the land away from the Native Americans at gun point, perhaps firing the first shots of what would be known as the “Indian Wars” three quarters of a century later.

Clark even contemplated invading what was then Spanish Florida and actually plotted creating his own empire, but it was never to be. He was exposed and made a final retreat back to Augusta, a shamed and bankrupt man.

Over time, long after his death, Clark regained his reputation and is consider by historians to be one of the largely forgotten heroes of the American Revolution.

Clark was buried on a hill out in an area near Lincolnton on land submerged now by the lake known as “Clarks Hill.” Clark’s remains were moved to the Community House grounds in 1952 before it would have been submerged.

Clarks Hill is not the only lake name associated with Clark, Lake Oconee and Oconee County are named after Clark’s fantasy republic as well as the Native tribes that once lived there.

And that’s something you may not have known.

Scott Hudson is the Senior Investigative Reporter and Editorial Page Editor for The Augusta Press. Reach him at scott@theaugustapress.com