As work continues on the I-20 bridge and is set to begin on the 13th Street bridge, many of us travel weekly over the several steel and concrete bridges linking Georgia and South Carolina with hardly a passing glance.

Civilizations throughout recorded history have thrived on the banks of rivers, which provide not just a cool drink but help sustain life by providing food fish and allow for trade through navigation and delivery of goods.

Crossing rivers where they become an obstacle, though, has always been a challenge.

While stone bridges from the Roman era still exist in parts of Europe, early North American settlers used different materials, and certain Native American tribes tended to be too nomadic to build bridges.

For those living on the Savannah River, early settlers found bridges to be impractical. Not only did the mighty Savannah seem to flood on a whim, easily washing away the sturdiest of structures, but the constant fluctuation of the water level meant that the wood and iron nails used to build them rusted and rotted away, no matter how much tar and pitch was used in construction.

MORE: Augusta faces tough budget calls on how to slash expenses, cut costs

Because of the interconnectedness, when a bridge failed, it tended to do so like dominoes, making them perilous at best and, of course, a navigational hazard that took weeks worth of hard labor to have the left-over debris removed.

Celebrated local historian Ed Cashin writes in his book, “The Story of Augusta,” that while the city of Augusta was chartered in 1736, it didn’t really take off as a settlement until after two things happened: the legalization of rum and the opening of the first river ferry in 1742 at the aptly named Sand Bar Ferry Road.

Some writings from the Federal period indicate that when President George Washington visited Augusta, he used a toll-bridge to cross into the city, but other documentation indicates he used a ferry.

According to an article in Augusta Magazine, at their peak, there were no less than 26 ferries in operation along the river from McCormick to just below Augusta.

MORE: Columbia County School Board approves issuing bonds for school upgrades

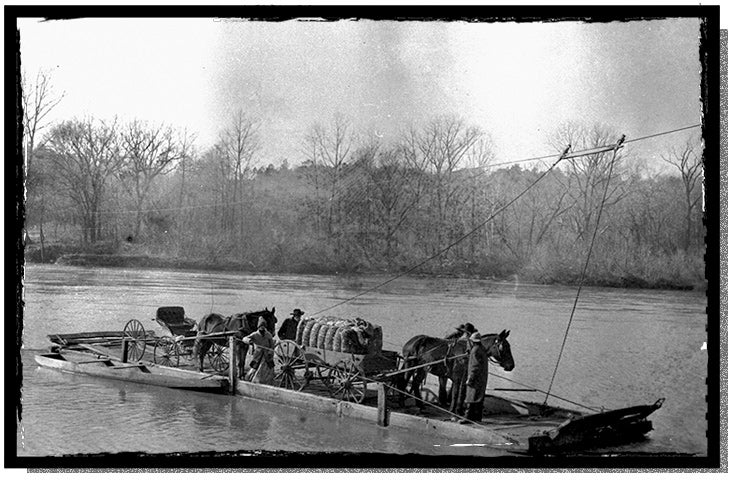

Augusta’s first ferries were operated by pole until the early 19th century when a chain was hoisted between the banks and they were either pulled by human grit or by a horse stationed on a treadmill. When the steam revolution came along, ferries became mechanized.

No matter the propulsion, the ferry operator had to be careful to know the gross weight of his cargo and balance it in such a way to prevent the craft from tipping over. Even though it seems dangerous to modern senses, the men “knew their craft” and there is not a single death in a ferry accident reported, according to Augusta Magazine.

Generally speaking, a ferry might be owned and operated by a local farmer as his side gig, but that meant passengers and salesmen, laden with goods to sell, had to wait until it was convenient for the operator to make the crossing. Later, a schedule announcing specific times throughout the day would be posted and people would either pay for themselves and their horse to cross, or the ferry would be loaded down with cargo, meaning it took more than one person to pull or pole the ferry across.

Being so closely intertwined with commerce, ferries could be the subject of business rivalries

According to historian Dr. Mark Newell, around the year 1800, John Hammond operated what was known as Hammond’s Ferry, a business that transported people and goods such as cotton and tobacco across the Savannah River. Hammond also himself owned a sizable cotton plantation.

His direct competitor in the ferry business was Ezekiel Harris, a tobacco and cotton farmer, for whom the Harrisburg neighborhood in downtown Augusta is named. The feud that developed between the two men would become legendary.

The rivalry would lead to one of Augusta’s earliest unsolved murders, that of John Hammond.

Harris and Hammond accused each other of burning their ferry boats out of revenge. But then one day Hammond’s body was discovered. He was dead of a gunshot.

Whether it was an outright murder or the result of a duel, the prime suspect obviously was Harris, but he was never convicted.

No matter, the death would hang over Harris’ head, and he was forced to leave the city and his once thriving business. The ferry Harris ran is long gone, but his house still stands on upper Broad Street and can be toured by appointment.

The ferries are all gone today, but, surprisingly, some ferries in rural areas still operated until the early 1950s; the only thing left of what was the safest and most scenic way to cross the Savannah are the street signs and neighborhood entrances bearing the names, Furys Ferry, Hammond’s ferry, and of course, Sand Bar Ferry Roads.

…And that is something you may not have known.Scott Hudson is the Senior Investigative Reporter, editorialist and weekly columnist for The Augusta Press. Reach him at scott@theaugustapress.com