Thousands of people gathered near the South Philadelphia pier that housed the SS United States for 28 years and watched as America’s “First Lady of the Seas” slipped out of the harbor and into the open ocean for the last time.

It was a bittersweet moment for people to watch the still confirmed fastest ship in the world be towed on its last voyage, on her way to the waters off of the Florida panhandle where she will continue to make the record books as the largest artificial reef in the world.

For many, the faded, once bright red funnels still offered a hazy glimpse into the bygone world of trans-Atlantic ocean liner travel.

Today, people cram into an aluminum tube strapped to jet engines, in a cabin with little room to stretch out, and suffer through seven hours of flying across the ocean with snoring aisle-mates and screeching children with only a package of peanuts and a watered-down cocktail for comfort. This is a far cry from the era of ocean travel, where it may have taken the better part of a week to make the voyage, but getting there truly was “half the fun.”

When the SS United States began her operational career in 1952, England’s longest serving monarch, Queen Elizabeth II, had just taken the throne, Ike Eisenhower occupied the White House, the church-house social for teens had given way to “sock-hops” and families crowded around the television on Monday nights to watch the antics of Lucy and Ethel on “I Love Lucy.”

During that time, the United States was emerging as the superpower of the West and was far more technologically advanced and industrially capable than any other developed nation, especially those in Europe which were still rebuilding the devastation from World War II.

The one sign of prestige that America lacked was that of a flagship ocean liner to rival the speed and luxury of the queens of the UK and France’s Liberte.

Despite the fact that the United States played an integral role in the development of steam power for ship propulsion, the country had never successfully entered the highly competitive world of oceanic travel. One main reason was that during the “heyday” of ocean travel in the 1920s, America remained in the grips of Prohibition and American-flagged vessels were not allowed to serve alcohol, even in international waters.

On the darker side, even with the defeat of the Axis Powers, the Nuclear age, along with the rise of the Soviet Union as the Superpower of the East, kept the entire world on the precipice of a potential World War III. In that arena, America boasted the world’s strongest army and most capable navy; what it lacked was the ability to move thousands of soldiers quickly halfway around the world to where they were needed for national defense.

The Navy brass decided to subsidize the building of a new superl-iner to the tune of $58 million, which is $921,245,900, or nearly a billion dollars in today’s money. The total cost was $78 million to build a troop carrier disguised as a luxury ocean liner.

What the Navy proposed was a luxurious commercial vessel that, at a moment’s notice, could be converted to carry and feed 14,000 troops 10,000 miles without refueling.

The result was the legendary SS United States.

William Francis Gibbs, a lawyer turned ship designer, was tasked with designing the new ship to the navy’s specifications. The vessel had to be the fastest ship plying the oceans, be considered more than just “practically” unsinkable and it had to be impervious to fire.

Gibbs was almost the perfect man to take up such a challenge, he was said to understand ocean liners the way some men have the innate understanding of horses. He was also a bit of an eccentric when it came to his problem solving abilities and work ethic.

In true American fashion, Gibbs did not set out to reinvent the wheel. Rather, like Henry Ford before him, he took advantage of the best innovations and combined them in one craft.

According to Mike Brady, producer of Oceanic Designs, at 990 feet long, almost 100 feet longer than the RMS Titanic, the United States was narrow enough, with a beam of 101 feet, to fit into the Panama Canal, but it’s slightly bulbous and raked bow made it surprisingly stable and not prone to rolling even in rough seas.

Gibbs relied on American ingenuity to drastically reduce the size of turbine engines which could generate the same horsepower and use less fuel than standard marine turbines. According to the SS United States Conservatory, Gibbs tapped pioneering naval engineer Elaine Kaplan to design the propulsion system.

Kaplan’s system had two turbine engines operating independently and placed so far away from each other within the hull that even if one engine was knocked out of service by a torpedo or mine, the ship could still move under her own power.

To work out vibration issues, Kaplan had four propellers installed, with the fore propellers having four blades and the apt propellers installed with five.

The actual top speed of the SS United States remains a state secret, but it was officially clocked at 38 knots, and those who were present on the sea trials maintain the ship moved as fast as 43 knots, making it the equivalent of a speed boat longer than four city blocks.

Some have even maintained the ship could keep up those speeds without all of the boilers being lit.

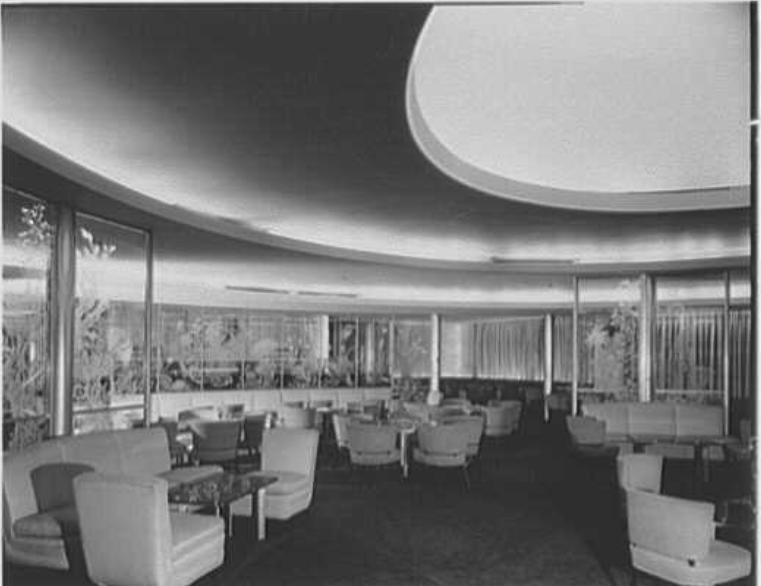

On the interior decks, one would be hard pressed to notice they were standing on a warship, even though there was hardly any wood used in the ship’s construction.

According to Brady, gone were the Georgian and Louis IV heavy paneling, palm courts and ladies’ drawing rooms of the Olympic Class era, replaced with a modern Art Deco design crafted mostly from aluminum and fire-resistant foam.

It is said that Gibbs only allowed for wooden butcher’s blocks in the galleys, and he, at first, ordered aluminum pianos from Steinway & Sons until the company proved they could make a wooden piano that could survive having an entire can of gasoline being poured on it and still produce the warm sound of a true Steinway.

Not only did the SS United States win the Blue Riband for both directions of her maiden voyage, a distinction the ship still holds today, but it captured the hearts of travelers from all over the world.

According to Brady, the ship has hosted four presidents; Truman, Eisenhower, Kennedy and Clinton have hobnobbed on her decks. The ship also became the favorite of the Hollywood crowd with Cary Grant, Carol Lombard, Frank Sinatra, the Gabor Sisters and John Wayne often being seen relaxing on deck.

The SS United States boasted a swimming pool, a full-size tennis court as well as ping-pong and shuffleboard; however, like the Mauritanias and Normadies of the past, the real treat of the voyage was the food.

Passengers could visit any one of the dining rooms and enjoy Iranian caviar, French foie gras and American Angus beef or order a sumptuous meal in-room.

The career of the SS United States came to an end in 1969 as she simply could not compete with jet planes, and since then, the ship has sat idle at port, a symbol of a bygone era.

However, unlike most of once great ocean liners, SS United States will go out on her own terms. Rather than being ripped apart by the scrappers, the grand old lady will serve an artificial reef and a living biological laboratory.

…And that is something you may not have known.

Scott Hudson is the Senior Investigative Reporter, Editorial Page Editor and weekly columnist for The Augusta Press. Reach him at scott@theaugustapress.com