A couple of years ago, I wrote a piece on Augusta’s history as a military ammunition manufacturing and storage site and one of our readers wrote me an email asking: “What was the public’s response each time the government came in and just took over land to build a bomb plant?”

Sometimes due to pure happenstance, and sometimes for good geographical and tactical reasons, the Garden City has been the location of a true “powder keg” where life and civilization blossomed while tolerating having a munitions facility that could spell doom for everyone living here in the blink of an eye, right in the back yard.

It is quite amazing that for almost 300 years people lived daily next to such a scary possibility, but a tragic loss of life on a titanic scale has never happened due to accident or sabotage.

I thought that was an interesting question to research, what was the public’s response to the gradual militarization of Augusta and the surrounding areas?

Throughout the city’s history, the feeling among the populace about the reality of a catastrophic situation has been: “Meh, there’s nothing we can do about it anyway.”

There is plenty of evidence that the city, sometimes begrudgingly allowed itself to become the great-grandfather of the military industrial complex.

When the age of aviation dawned, the good people of Summerville protested having an airfield nearby for fear of a single engine plane crash happening on their property, but meanwhile, hardly anyone in the city seemed to be particularly alarmed to have enough gunpowder to sink 100 ships the size of the RMS Lusitania parked within view from the kitchen window.

In World War II, despite warnings of saboteurs everywhere, to see enemy prisoners of war walking the streets unguarded in wartime was normal; and the people walked unwittingly past fallout shelter signs hung all over downtown Augusta until a relatively short time ago.

Even historians seem to be rather lackadaisical when it comes to identifying Augusta as the “powder keg of the South.” Even the revered Ed Cashin only devotes a total of four pages of his book, “The Story of Augusta,” to the Confederate Powder Works.

In fact, only the lowly mosquito has managed to temporarily halt the manufacture and storage of munitions in or around Augusta shortly after the original magazine was constructed down on the banks of the Savannah River in 1819.

According to Cashin, those original buildings were less an arsenal than just mainly a munitions dump with around 30 enlisted men hanging out playing cards and probably smoking their pipes. In that same year, every last soldier stationed there died of mosquito-borne diseases.

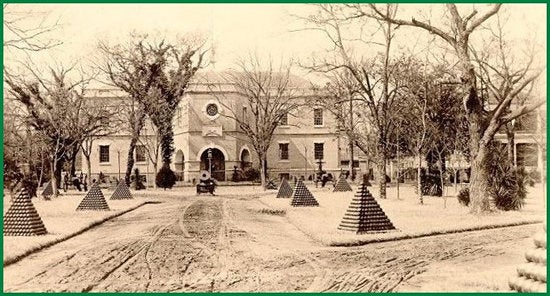

The residents of Summerville did protest mildly at the thought of having to walk past a military installation on their way to Mealing’s Meat Market; but, even in those days, what the federal government wanted, the federal government got, and it got the primo of primo real estate on the top of the Hill.

Around 40 years later, when talk came of placing the Confederate Powder Works facility in Augusta, there was really no discussion to be had. While the rest of the South was almost totally agrarian, Augusta was known as the “Lowell of the South,” for its seven-mile-long industrial canal and heavy manufacturing prowess.

Augusta, at the onset of the Civil War, was also a major hub of the railway system, making the city’s location a real ‘no brainer’ to manufacture, store and then ship gunpowder. Curiously, Cashin does not record any public backlash for a plan to put a gunpowder manufacturing complex within walking distance of private homes when the permanent facility was announced.

There likely is very little meaningful discussion on the issue in the historic record because, for the Confederate government to win the war, it needed the powder works complex, and it got what it needed. There was nothing left to say on record.

By the time of World War II, Augusta was well used to being a town alive on top of a powder magazine. A German POW wandering around Summerville near an ammunition dump, under no supervision, was not even a cause for panic.

Most of the German inmates were sent out to work on farms and logging operations in Burke, Columbia, McDuffie and Aiken counties and likely came back to their camp on the Hill too tired to cause mayhem.

According to Cashin, some of the arsenal prisoners would be used to repair roadwork in Summerville, and occasionally a prisoner would sneak off the job, likely with a hidden flask looking to be refilled, only to be reported by what Cashin called “obliging housewives.”

Those women, being Southern of course, likely offered the prisoner a slice of pecan pie and a cold glass of milk while they waited for the MPs to pick them up.

The Cold War really could be called America’s first ‘terror’ war, as the thought that entire cities could be consumed and devastated at random and purely by the push of a button, taunted the entire nation.

In an age of nuclear uncertainty, Americans all across the CSRA, put up no real protest at plans to put a nuclear weapons facility right smack-dab in the middle of a thriving community, thereby, destroying the community with the stroke of a pen, rather than the push of a button.

SRS was needed to prevent World War III and it had to go somewhere was the prevailing thought of the day; and the protestations of the farmers of the Ellenton area were largely ignored over time and the plant went up and presided over the landscape for decade brewing a product of death and destruction.

At one time, the Savannah River Plant manufactured and stored enough nuclear weapons to make Hiroshima look like a test run in total human annihilation.

The government chose to operate in secrecy, and the public, sitting in the shadow of the fear of the mushroom cloud, made nary a protest of any real determination. Those who warned against nuclear proliferation, including President Eisenhower, were largely ignored by the press of the time.

Virtually every credible citation, including those on the Department of Energy states that the Savannah River Site was built in “the early 1950s,” a definitive date is not available. Most people of the time, especially those who worked there referred to it simply as the ‘Bumb Plant.’

The town of Ellenton, S.C., was engulfed and ceded to the federal government, leaving behind a few markers and little else than a lyrical epitaph by Jesse Johnson and Dixie Smith:

“Oh, the friends we know and love,

We’ll meet upon some other shore,

For Ellenton–fair Ellenton

Is gone forever more.”

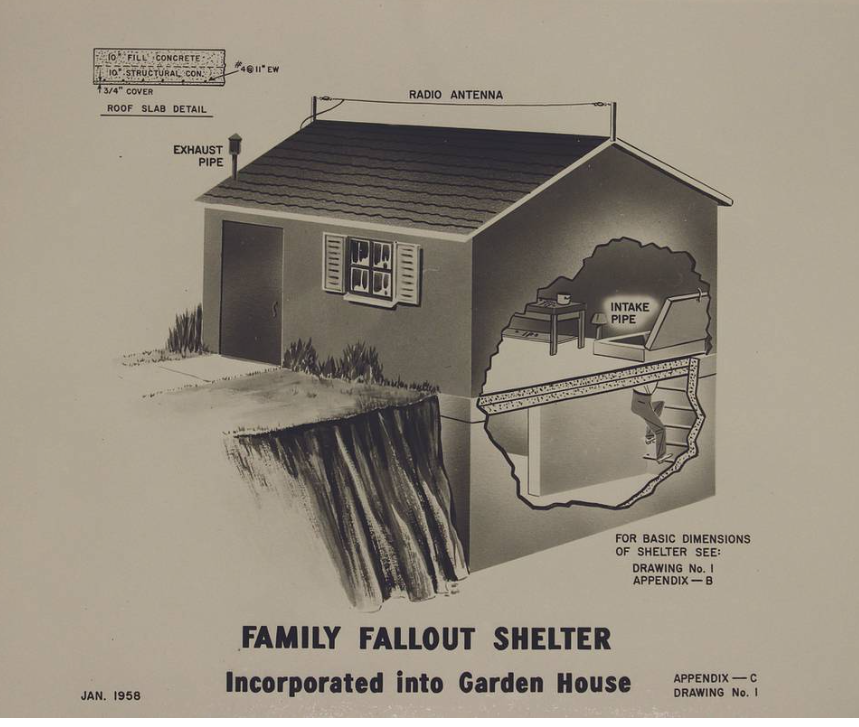

Like the wars before, the danger of a catastrophic explosion was taken in stride among the public. While news announcers on radio and, later, television, covered every aspect of the Cold War with breathless anticipation of each international chess move, the Sears Catalog declined to add bomb shelters to its list of available “construct it yourself” housing. People wanted to buy new Pontiacs for themselves and Radio Fliers for the kids and knew that there was little use of a bomb shelter in the back yard when the family could enjoy a pool.

Even grade school children ridiculed the idea of ‘nuclear fall out’ drills.

During the Cold War, local radio station WGAC had a bomb shelter built as an annex to its transmitter building. The ‘nuke proof’ shelter added on to the back of the building sported all the necessities in the case of SRS being bombed or an accident occurring at the site: first aid, water, canned food and blankets were packed into a full service radio studio and Spartan living area. However, the walls of the ‘shelter’ were only two cinder block-lengths thick and the radiation exposure from a blast 45 miles away as the crow flies would have had the same eventual outcome as shielding under a school desk during a ground-zero blast, if the wind conditions were right.

Radio veterans have recalled that the WGAC bomb shelter still had the iodine pills and sealed glass bottles of water in the 1970s, but the room was more of a ‘party room’ for disc jockeys and their groupies.

Radio Icon Morning Man George Fisher acknowledged that there was nothing that the straight-laced announcer could do about the smell of marijuana emanating from the WGAC bomb shelter when he would go in to work and relieve the night jock.

“Oh, they thought since there was a separate ventilation system that the smell would stay inside the shelter, but it didn’t. I’m surprised I didn’t get some kind of contact high with all those fumes,” Fisher once said.

…And that is more of something you might not have known.

Scott Hudson is the Senior Investigative Reporter and Editorial Page Editor for The Augusta Press. Reach him at scott@theaugustapress.com