Photos or sketch portraits of all of Augusta’s mayors line the walls of the Augusta Commission’s chambers in the Municipal Building downtown; the images go all the way back to the year 1798 when Thomas Cumming was elected, or so they say.

Cumming was not Augusta’s first mayor, nor the second or third; the distinction of holding that title goes to one Abraham Jones, he was the first in a string of mayors that gave up after a year or two, thereby forming the list of early Augusta mayors that history forgot.

The “town” of Augusta actually got along, from its founding in 1736, for well over 50 years without a formal elected government. Now, after nearly 290 years, Augustans are still wrangling over the composition of it’s charter, and the central issue plaguing generations has always been the powers bestowed on the mayor.

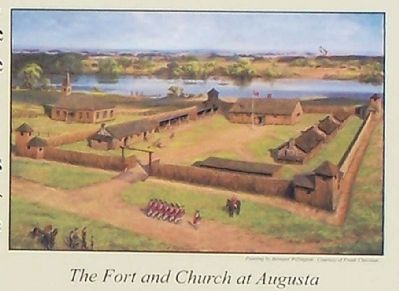

Augusta’s founder, British General James Oglethorpe, established early Augusta primarily as a military outpost and later, when the capital of the colony of Georgia was moved to Augusta, most felt that the state government housed here, by way of the General Assembly and state Supreme Court, was all the government the area needed.

According to the late Augusta historian, Ed Cashin, in his book, “The Story of Augusta,” in most people’s minds, Augusta was chartered as a “town” and not a “city” like Savannah, so there was really no need for yet another layer of bureaucracy making up rules and regulations that would serve only to nettle the fur traders that called Augusta a home base.

In fact, calling Augusta a “town” was a bit of a stretch, just like calling Georgia, in those early years, a colony, when it was really only that on paper. Augusta was, at that time, the final frontier outpost of the South and the “colony” of Georgia really only existed on maps as nearly all of the land west of Augusta was Native American territory and those inhabitants didn’t care that the king of England had planted his flag in the soil, most of Georgia was their territory.

As far as the Native Americans were concerned, the settlers could draw lines on maps all day long, but they were not interested in the Europeans coming in and making laws that might impede their interests, so they largely ignored the White men, and the White men knew not to challenge them too far.

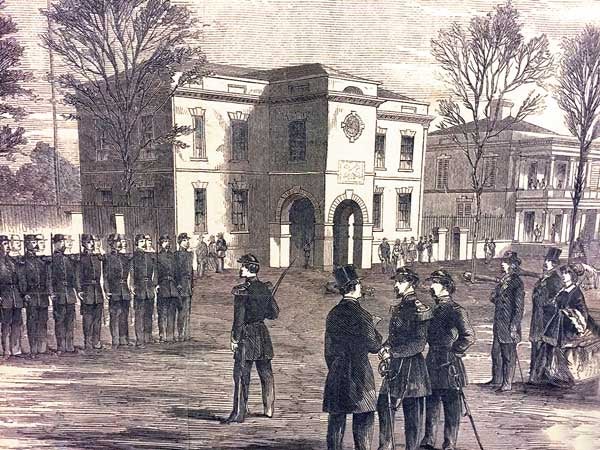

In 1782, a year before the Revolutionary War ended, some people in town began clamoring for a civilian government as the military leaders and state leaders were not very effective in managing a growing society, yet it would be another seven years before the first city council was seated, according to Cashin.

In an illustration of how politics in Georgia are slow to change, many Augustans did not recognize the new city council as being legitimate, claiming that since non-residents (Native Americans) were allowed to vote, then the entire vote was fraudulent.

Cashin writes that the new council of aldermen were seated in 1790 and Abraham Jones was selected by the body to act as mayor, which was the method to elect a mayor proscribed by the town charter.

By this point, Augusta’s government structure began to mirror that of the new nation, in that, under the Articles of Confederation, the United States was recognized as sovereign nation, but the government that had been cobbled together was about as effective as someone trying to use a sieve as a bucket.

Similar to what was happening at the federal level, Jones and the aldermen passed taxation ordinances that were summarily ignored, and no one wanted to be the one tasked with collecting taxes. After all, nettlesome bureaucrats could still be subject to tarring and feathering by the unruly mobs and later, no matter the evidence, no one would claim to have seen anything.

According to Cashin, the first council did not last long as it was discovered in July of that same year that two of the elected aldermen were themselves not “residents” of Augusta.

It also appears that Jones, as mayor, wasn’t all that popular either; after all, the colonists had just shaken off the king of England and didn’t like the thought of a local despot calling himself a “mayor” and making the rules. So, the first government was disbanded merely seven months into its existence, partly because no one in the public paid attention to the council or what it did or who it tried to tax, and partly because the commission and mayor were always at odds.

Problems and conflicts remained with no civil remedies; such as when people would let their pigs and other livestock wander freely throughout the town, damaging property, the injured party had no authority to turn to.

A second council was seated, but Cashin writes that they were even more ineffective than the first and only lasted a year.

In 1793, a third election was held and this time, it was a fellow by the name of John Milton that became mayor. Unlike his predecessor, Milton was apparently one that did not take any guff and was able to pass and enforce ordinances such a ban against firing weapons in the streets and galloping horses through town and, yes, an ordinance that mandated the proper securing of one’s pigs.

Milton’s administration did not last long either, according to Cashin, he and the council could agree on building a city market, but they agreed on little else and before long, gridlock set in.

Cashin writes that Milton became so bored with the job that he took on a side gig as Governor Telfair’s secretary. The local government ended up becoming so ineffective that the General Assembly finally revoked Augusta’s “town” charter. At that point, all emergency civic functions of the local government were left to the Trustees of the Academy of Richmond County.

To add insult to injury, around the same time, Augusta lost the distinction of being the state capital, as the seat of state government was moved to Louisville.

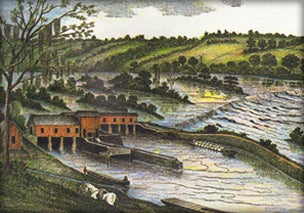

In 1798, two years after a massive flood washed away the Hampton Bridge and left Broad Street under two feet of water, Augustans applied for a new charter, this time, the charter was for a “city.”

Under the new charter, though, Augusta did not have a mayor, but rather employed a succession of individuals tapped by the council to act as the “intendant.”

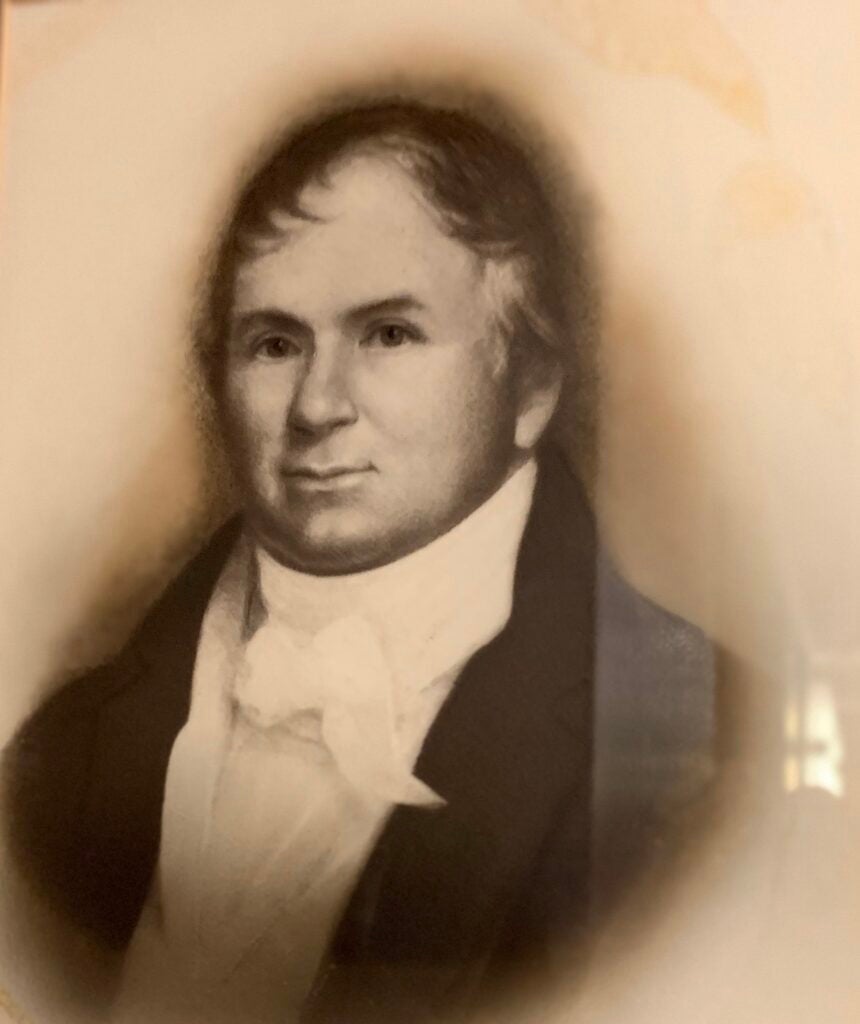

The first intendant was Thomas Cumming and he became one of Augusta’s forefathers, quite literally. His son was Henry Cumming, the man who made building the Augusta Canal his life’s passion; his efforts earned the Garden City of Augusta the nickname of “the Lowell of the South,” for it’s manufacturing prowess.

Technically speaking, the elder Cumming, the man whose portrait hangs in the commission chambers today and is labeled as Augusta’s first mayor, never actually held that title.

…And that is something you may not have known.

Scott Hudson is the Senior Investigative Reporter, Editorial Page Editor and weekly columnist for The Augusta Press. Reach him at scott@theaugustapress.com