Just to set the record straight, famed inventor Eli Whitney was not born in Augusta, he did not own property in Augusta and there is no record that he ever visited Augusta. However, he did leave an indelible mark on the Garden City and, indeed, the world.

Augusta has its share of proven historical events that happened here and it has plenty of myths as well. Sometimes, the truth behind the myths are even more fascinating than the myths themselves. Such is the case with Eli Whitney, historically known as the inventor of the cotton gin and heralded by some as the father of modern manufacturing.

In the early 19th century, tobacco was the main cash crop throughout the South. Giant warehouses for curing tobacco dotted the landscape all along the Savannah River in Augusta.

Something You Might Not Have Known: The Ezekiel Harris House

However, unlike other staple crops, tobacco leaches nutrients out of the soil, rendering the land fallow after as little as five years.

Cotton became a great alternative, but it too had its drawbacks. Long Staple cotton has seeds that literally fall out of the boll, but that variety can only be grown in coastal areas. The other varieties, however, contain sticky seeds, making the deseeding process long and arduous.

Whitney, a New England native and student of (then) Yale College, traveled to South Carolina after receiving a job offer to tutor the children of a wealthy plantation owner. Upon arriving, Whitney was turned away, as the job had already been filled.

[adrotate banner=”19″]

Whitney found himself running out of money and was given an invitation by the widow of Revolutionary War hero Nathaniel Greene to come stay at her home in Savannah and continue his law studies.

It was during his brief time in Savannah that Whitney learned of the trouble farmers were having in turning cotton into an actual cash crop and in 1793, he began working on the invention that would make him famous.

Whitney’s cotton gin was a relatively simple device that pulled the cotton threads through a series of “ginning ribs,” separating the seeds from the boll.

One of Whitney’s early prototypes was apparently sent to and used at a plantation in Augusta, but there is no evidence that Whitney accompanied his invention to Augusta.

Whitney’s invention would bring him fame, but not fortune. Because of the simple design, it was easy for others to replicate the device and Whitney was left nearly bankrupt trying to enforce his patent.

To his disdain, several people would file their own patents, claiming Whitney was not the original inventor of the cotton gin. The ensuing legal battles left Whitney broke.

In a terrible case of irony, Whitney thought his invention would help put an end to slavery, but it did the exact opposite. A disillusioned Whitney looked on as cotton plantations grew larger and required even more enslaved people to handle the massive increase in cotton production.

[adrotate banner=”31″]

Years later, Whitney would come up with another idea that would have an even bigger impact than the cotton gin and this idea would finally make him rich. Whitney was given a grant by the federal government to produce muskets, and that was when he developed the idea of interchangeable parts.

At the time, muskets and virtually every other tool with moving parts were made by hand. If one of the many parts failed, tools such as muskets became useless and were simply discarded. One loose screw could consign an entire machine to the trash pit.

Whitney’s idea of standardizing parts and making them interchangeable helped spark the industrial revolution.

Much later on, Henry Ford and others developed Whitney’s ideas further, creating the mass production line.

Whitney’s ideas would transform Augusta from a sleepy trading town on the Savannah River into an industrial powerhouse based on the production of textiles made from ‘King Cotton.’

At the peak of the King Cotton Era, the riverfront area was crammed with warehouses filled with cotton. Many of those buildings survive, at least in part, to this day.

[adrotate banner=”22″]

In 1868, the grandson of one of Whitney’s cousins, Seymour Murray Whitney, moved to Augusta, intent on becoming a cotton farmer and broker. He and his wife settled at a home listed as 15 8th Street, which is directly across the street from the Cotton Exchange building that was built in the mid-1880’s.

An interesting side note is that the Cotton Exchange building was apparently used for trading cotton during the daytime and a venue for cock-fighting at night.

Seymour Whitney’s company, S.M. Whitney Co., would become the dominant cotton brokerage firm in Augusta and would continue on for nearly 150 years, finally closing its doors in 2010 as textile manufacturing continued to move overseas, emptying the mills and the warehouses.

Because the Whitney name became so prominent in Augusta, naturally, myths began to emerge.

Stories abounded that Eli Whitney secretly developed the cotton gin in Augusta with the aid of a slave named Sam. While “Sam” might have existed, he most certainly was not from Augusta. Indeed, there is no evidence that Whitney ever spent a night in the Garden City.

Something You Might Not Have Known: J.B. Fuqua

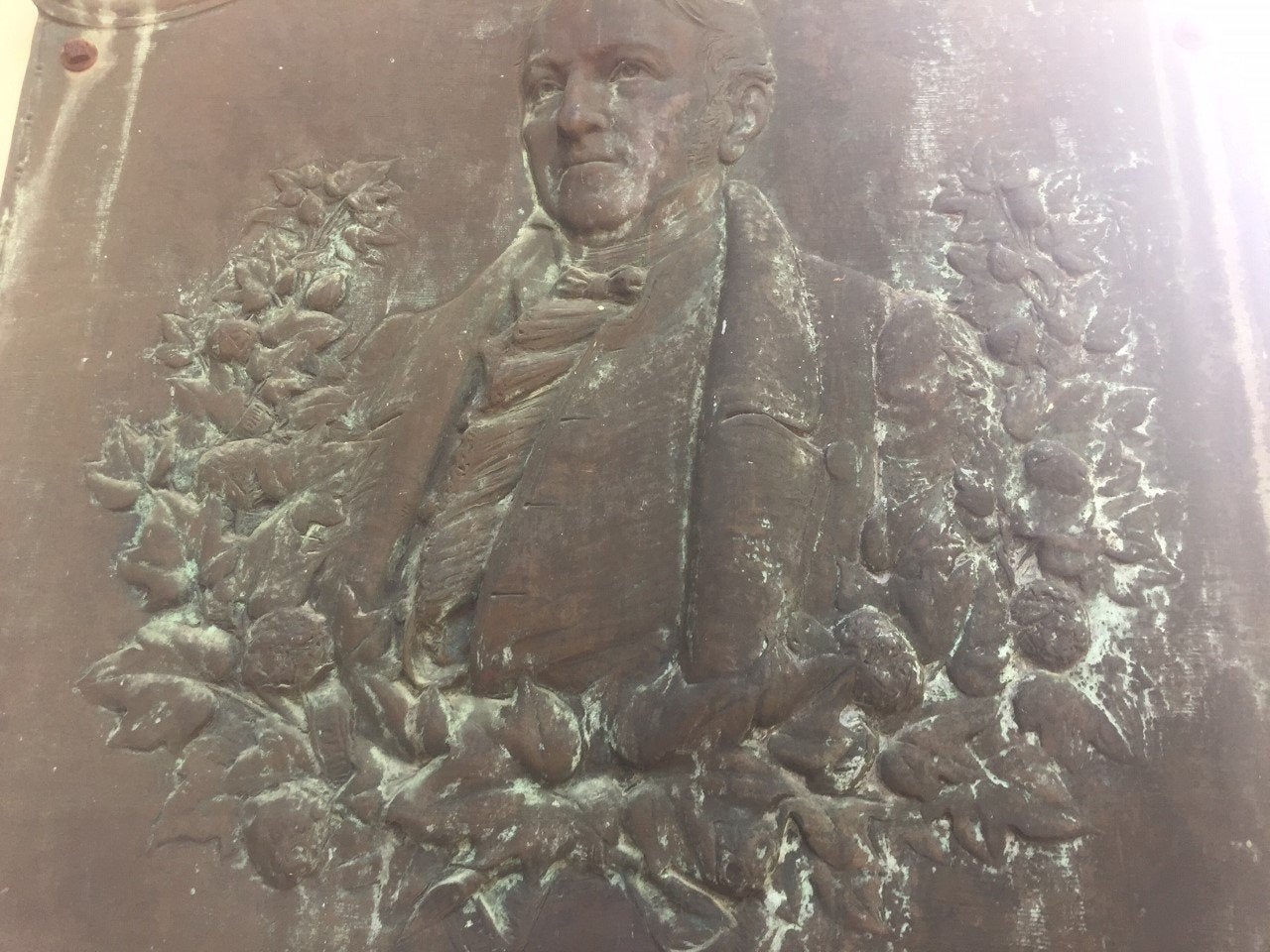

A large plaque was placed on the former Whitney family home in 1902 dedicated to the man that transformed Augusta without ever stepping foot on Augusta soil. So, perhaps Eli Whitney can be recognised as an “honorary” Augustan.

…And that is something you might not have known.

Scott Hudson is the Managing Editor of The Augusta Press. Reach him at scott@theaugustapress.com.

[adrotate banner=”37″]