Augustans are realizing the decades-long decline and downward spiral of the historic Bon Air property, located at 2101 Walton Way, and wondering just what went wrong with the Summerville landmark and the historic property can be recovered.

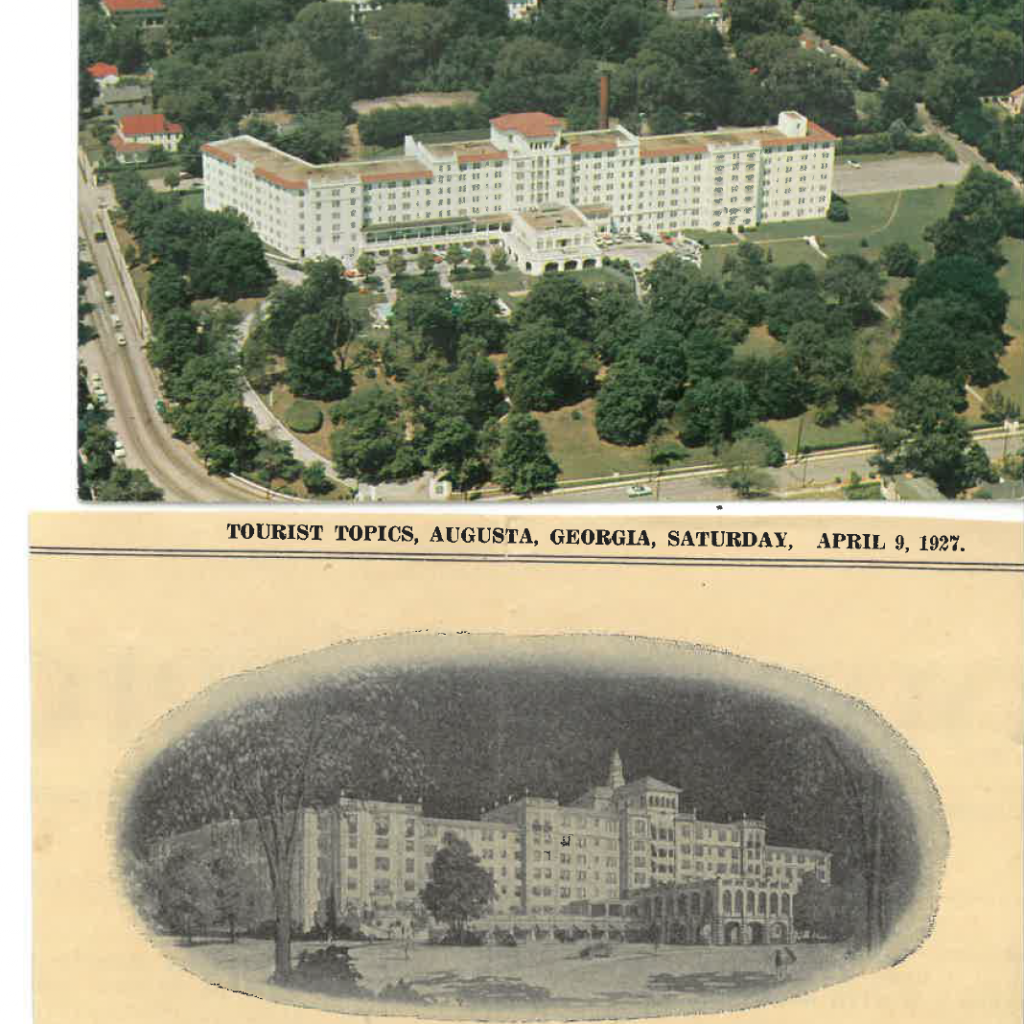

Today, the former Bon Air Hote sits perched towering over the city as a relic, a haunting reminder of several bygone eras. No one alive experienced the historic property at its zenith, but it was once the crown jewel of Augusta high society.

“I just left the Bon Air, and I can tell you that I am glad I was wearing a mask because the smell was overpowering,” said District 3 Commissioner Catherine McKnight after she took a short tour of the building on Jan. 26.

According to McKnight, the building shows clear signs of plumbing damage and water leaks. One tenant told her that she has experienced what seemed like rain coming down inside of her apartment.

“Seeing it in that shape really made me want to cry. My great aunt, who everybody called Cat, like me, lived there in the late 1970s, and it was so nice; it was luxurious,” McKnight said.

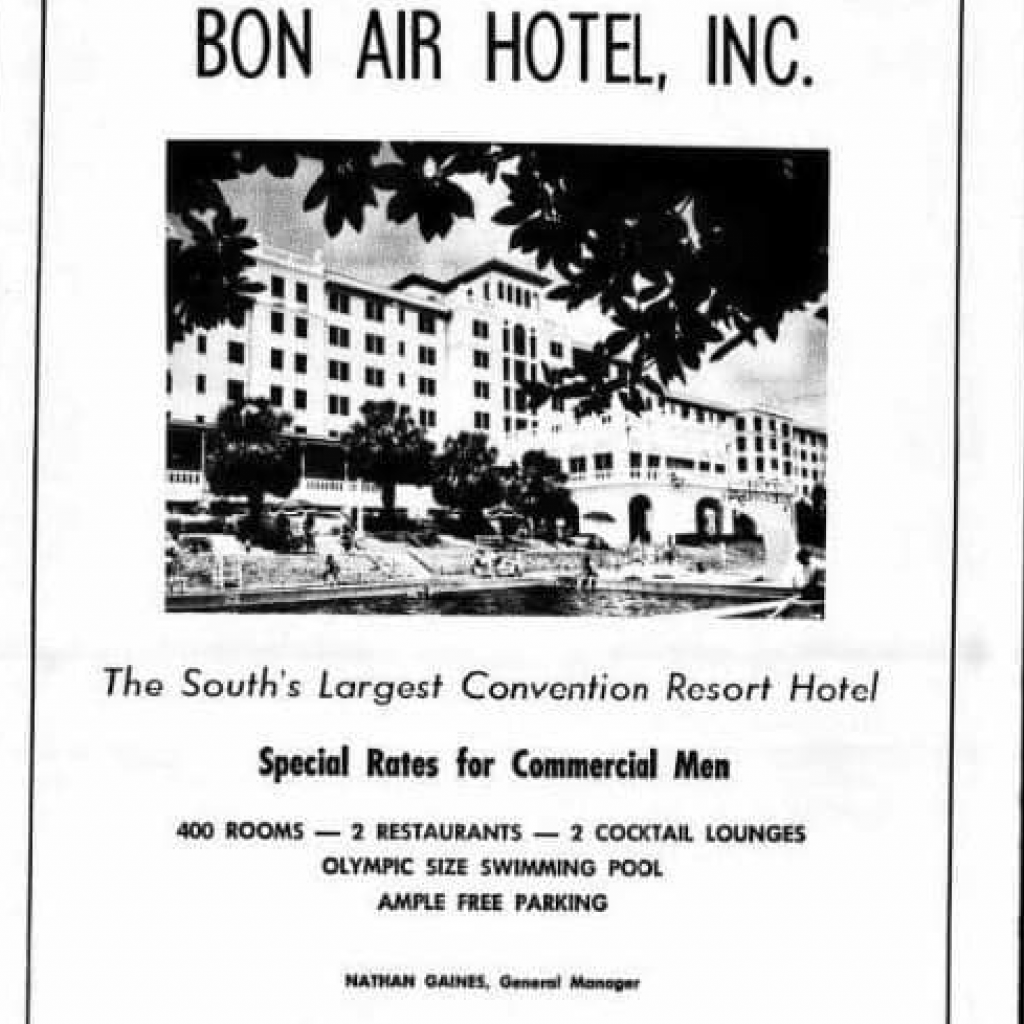

When the original Bon Air was built in 1889, the five-story wooden structure was meant to cater to wealthy Northerners who preferred to escape the frigid snowstorms of the north and come to the more palpable climes of the American South in winter.

Since Augusta was the end of the East Coast rail line at the time, winter tourism became a big business in the growing town. The Bon Air was constructed to meet the needs of the vacationers, offering Gilded Age opulence with all the amenities such as an indoor putting green, culinary feats of excellence and a giant ballroom that was the scene of elaborate parties for the tuxedo and ball gown crowd.

According to Stan Byrdy, author of the book Augusta and Aiken in Golf’s Golden Years, President William Howard Taft was known to have stayed in the Terrett Cottage, which was behind the main Bon Air building, during the winter of 1908-09 when he was president-elect. Taft spent his time playing golf and selecting cabinet members for his upcoming administration.

At the time, the Bon Air Hotel managed its own golf course, which eventually became the Augusta Country Club of today.

The original wooden building burned to the ground in 1921 and was replaced with a new stone and steel structure two years later. The new structure would boast rich wooden paneling that held up delicate works of art and featured glittering chandeliers throughout, while the facade seemed to be impervious to the fires that destroyed many of the grand hotels of the era.

So-called palace hotels of the time, the Bon Air included, were transitioning from the stodgy Edwardian look to the new Art Deco style, and most interiors took on the cleaner, more rounded look of that decor style while still preserving some of the traditional Georgian and Edwardian cues.

Palace hotels still featured hours-long multi-course dinners, palm courts, smoking rooms and the precursors to the modern spa, but they did away with the rooms for ladies to retire to after dinner. The ladies of the 1920s did not want to retire; they wanted to smoke forbidden cigarettes, enjoy highballs and cavort just like the men.

Fresh off the ratification of the 19th Amendment, which gave women the right to vote, the “flappers” of the era were done with corsets and wanted to do everything other than “retire” to a sitting room while the men caroused.

The late Augusta historian, Ed Cashin, wrote in his book The Story of Augusta, that the winter vacation crowds were pleased to find Augusta “roaring” in the Prohibition era of the 1920s. Liquor at the Bon Air Hotel flowed freely.

City leaders were keen to the fact that, should a surname such as Vanderbilt or Rockefeller show up on a police blotter charged with imbibing alcohol, the arrest would be covered in the national newspapers and could destroy Augusta’s tourism trade. Cashin notes that even the feds turned a blind eye to “America’s wettest town.”

According to Cashin, the winter of 1925 was the peak year for the winter crowd with 2,300 people staying at the Bon Air Hotel over the cold season.

Augusta’s time as a tourist destination was short-lived. The rail lines were extended into Florida, where, instead of having to endure a mild winter, people could have virtually no winter at all.

The Great Depression could have spelled doom for the Bon Air Hotel, but one little golf tournament breathed new life into the famous hotel. The founding of the Masters Tournament in 1934 was a big deal for the owners of the Bon Air Hotel as golf legend Bobby Jones made it the “unofficial” hotel of the tournament, according to Byrdy.

“Pretty much all of the golfers stayed there, and the ballroom was in constant use as a room for parties as well as press conferences. I would say that the Masters had a large part in saving the hotel during that period,” Byrdy said.

World War II dealt the Bon Air Hotel a serious blow as the Masters was canceled during the conflict, and people were not traveling for pleasure during wartime. After the war, the grand hotel would rally back as President Dwight David Eisenhower would bring even more attention to the sport of golf, the city of Augusta and the Masters.

Eisenhower and his wife Mamie became regulars of the Bon Air Hotel, according to Byrdy.

Yet, it would not be enough. Unlike the tournament of today, the Masters tournament of the 1950s did not reached a mass audience. According to Byrdy, it was when CBS Television began airing the tournament in the early 1960s that the Masters Tournament really came into its own as an international event.

It is important to note that hotels such as the Bon Air were once not only lodging for travelers but a year-round community gathering spot. The Bon Air had retail spaces, a barber shop and hosted ballroom dancing lessons and even theatrical performances. The Bon Air Hotel’s restaurant was considered the pinnacle of fine dining long before the Pinnacle Club came along.

According to press reports in the late 1950s when America was experiencing an economic recession, ownership of the hotel changed multiple times, and people began complaining the aging structure had lost quite a bit of its luster. Due to financial limitations, the once grand hotel ceased operations in 1960 and was converted into a retirement home.

Over time, though, the term “old folks’ home” became obsolete as retirement “communities” and “assisted living” became the norm. The Bon Air, with no longer a working kitchen and devoid mostly of senior activities that modern communities provide, fell out of favor for those with the financial means to live the high life in their elder years.

The Bon Air now has become simply another Section 8 property and has all of the problems that come with Section 8 housing, according to McKnight.

“I get reports of people sleeping in the stairwells, gunshots fired in the parking lot and drug deals happening out in the open. It has no resemblance to the place my Aunt Cat once lived in,” McKnight said.

McKnight said that really all the Augusta Commission can do at this point is use the planning and zoning ordinances to protect the structure from any further damage. The current owners of the property, Redwood Housing of Austin, Texas, have applied for a variance to be able to slice the once famous Bon Air ballroom into separate loft units and the Commission has voted against such plans.

Byrdy, who says he has another book on Augusta history due in late spring, is somewhat optimistic about the future of Bon Air. He contends that the incredible growth of the Masters tournament over the years could one day open the door for a complete revitalization of the old hotel.

“I don’t think it will be long before we start referring to April as ‘Masters Month’ instead of ‘Masters Week.’ If someone decided to put in the time and the investment, I believe it could thrive as a hotel again because of its history with the Masters and the game of golf itself,” Byrdy said.

Byrdy says that he knows of people with significant interest in the future of the property, but the former Augusta television newsman says we have to wait to hear the rest of the story.

“I think the building can be revived and I think it will be, but that’s all I will say for now,” Byrdy said.

…And that is something you might not have known.

Scott Hudson is the senior reporter for The Augusta Press. Reach him at scott@theaugustapress.com