(Editor’s note: This is the second in a series of stories about economic development in south Augusta, its rise, fall and possible rise again)

By 1964, the economic development nonprofit called the Committee of 100 had drawn plenty of industry to the Garden City.

In June of 1968, the Augusta-Richmond Planning Commission published its Commercial Area Study of the city and county, containing research conducted by Gould Associates and Muldawer & Patterson.

The study purported to “provide estimates of expansion potential” in commercial developments, and to offer projections and recommendations on the course of future expansions and improvements.

The report’s section on the “Highway Strip Commercial Area” described Gordon Highway as ugly and uncontrolled; and the Southgate shopping center complex as “virtually lost” in Gordon Highway’s “chaotic strip development.”

Also in the summer of 1968, the Planning Commission published its Master Plan for Land Development. It contained a report of population and development trends current up to 1965, and forecasts of the same, up to the year 1985.

That study estimated Augusta’s total labor force in 1965 at 79,908 people, and that 11,999 of those citizens were employed in manufacturing. It also projected a 58% spike in that number of manufacturing employees by 1985.

In 1970, just months after the Augusta Riot, the Southern Regional Office of the National Urban League published its own study, “Social and Economic Audit as It Relates to the Black Community of Augusta, Georgia.”

That report cited difficulties in attaining information on the housing conditions of African Americans in Augusta at the time, particularly regarding census data.

It notes confusing data on non-white households, and suggested that the 1960 Housing Census Data for the Augusta-Richmond County area was “worthless” due to “gross inaccuracies,” and assessed that the 1970 census data was likely to be even more inaccurate.

“It seems apparent that inaccuracies tend to work to the detriment of Black residents of this geographic area, both in terms of their inability to participate in the census process… and the fact that conditions in areas of Black residential concentration suffer from the grossest inaccuracies of data collection,” said the Urban League’s report.

The document goes on to say, however, that even through the inaccuracies, significant inequalities were still obvious in the data.

“Using the criteria of ‘soundness and all plumbing fixtures,’ the City of Augusta housed only 34.6% of its 5,412 non-White renters in adequate rental units,” said the audit report.

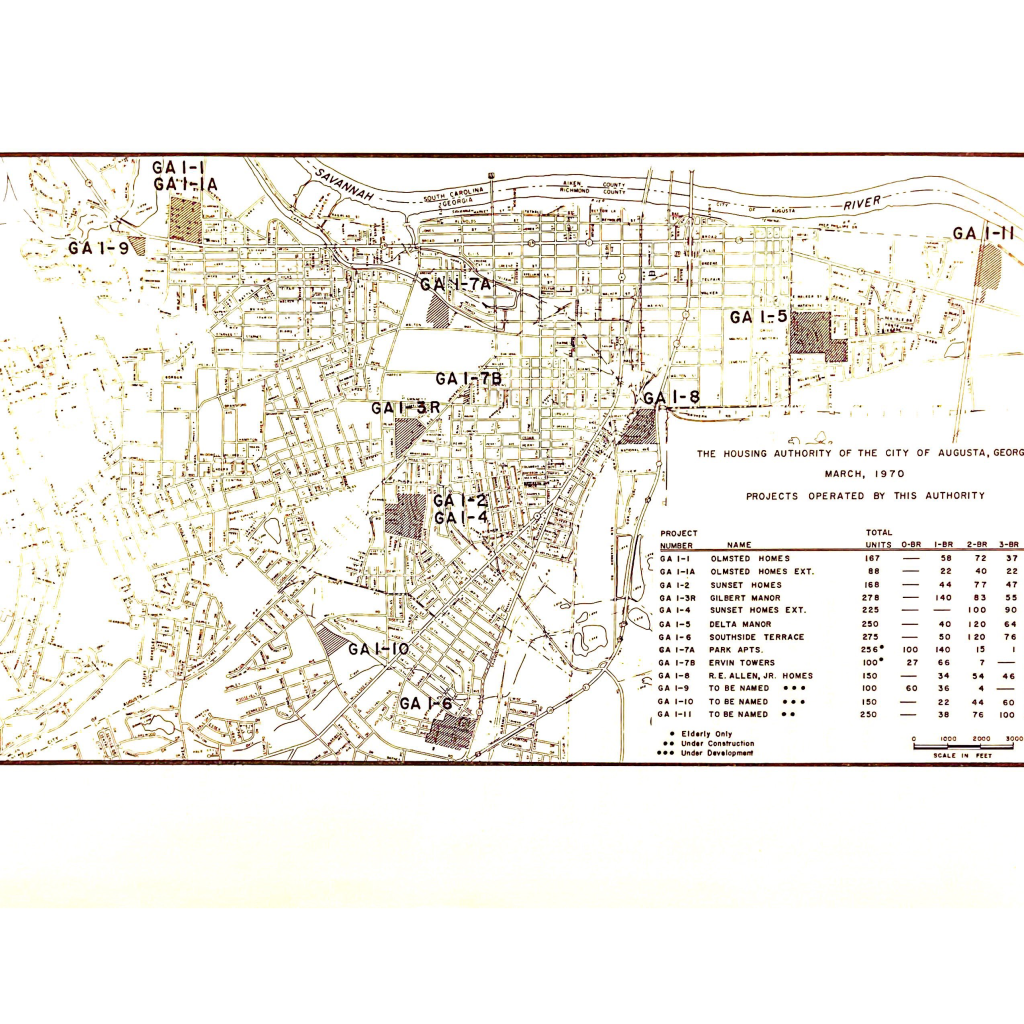

Most of this was regarding public housing in the area, such as the Southside Terrance neighborhood.

But the study did acknowledge the Bell Air Hills subdivision as an “example of private residential development” accomplished by African Americans. Pioneers, Inc., subdivided and sold 60% of 512 lots along more than 300 acres near Fort Gordon, according to the document.

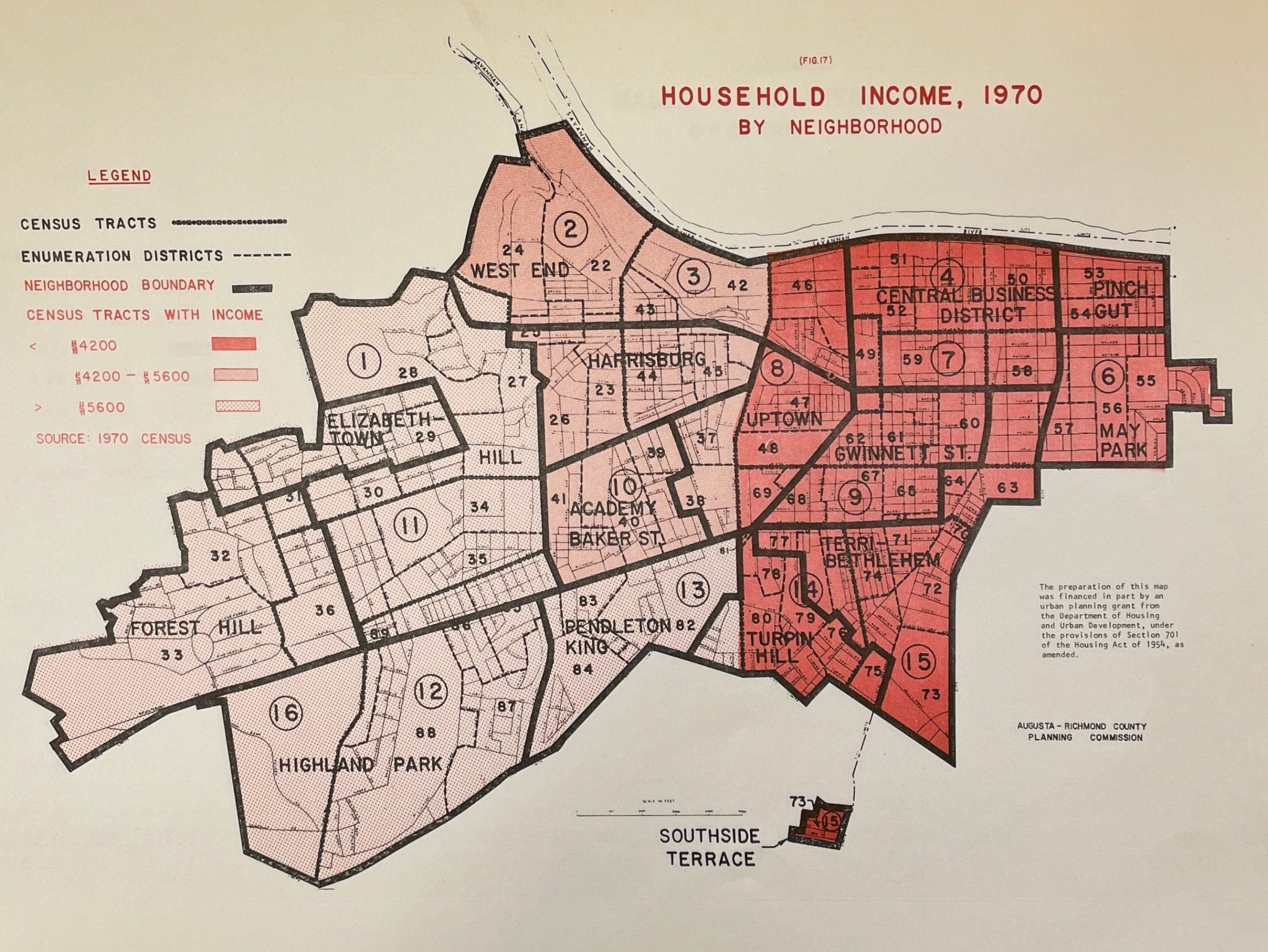

By June of 1975, the Augusta Planning Commission had produced its “Neighborhood Analysis” report, partly financed through a grant from the Department of Housing and Urban Development.

That study only covered so much of the southernmost parts of the city. It noted that the majority of the 1970 population of what was then known as the Terri-Bethlehem neighborhood were “low-income and Black,” that portions of the neighborhood were “seriously lacking in spatial organization… to effectively serve the population and an adequate supply of housing;” and claimed that the population was “not entirely capable of making massive improvements” because of its “low educational and income levels.”

The analysis did note that the Turpin Hill neighborhood fared somewhat better, with higher rates of owner-occupancy and only 3.4% of homes lacking plumbing; but also cited low rents ($47 a month) and high stats of overcrowding.

Southside Terrace, a public housing complex located “over one-half mile south of the remainder of the City off Old Savannah Road,” received slight attention in the neighborhood analysis, which mentioned primarily that that the area’s population was nearly 100% Black, some 61% of which were children, and that “it can be assumed that the educational level and income is lower and unemployment higher than what is shown in the tract statistics.”

The several statistical maps in the Neighborhood Analysis, not delving further south than Highland Park, shows the predominantly African American Terri-Bethlehem and Turpin Hill as among the lowest income areas in 1970, but among those with the fewest unemployed males.

A 1973 stat map showing locations of major crime shows a small smattering of dots concentrated in those areas as well, but not as densely as the Gwinnett Street neighborhood, or Downtown (referred to as the Central Business District).

The Committee of 100 jump-started the spread of industry toward the mostly rural and slowly burgeoning south Augusta in the 1950s. As it would be on the cusp of the 1980s before Edward DeBartolo would develop the Regency Mall, the area struggled to find itself in the years between.

Skyler Q. Andrews is a staff reporter covering business for The Augusta Press. Reach him at skyler@theaugustapress.com.