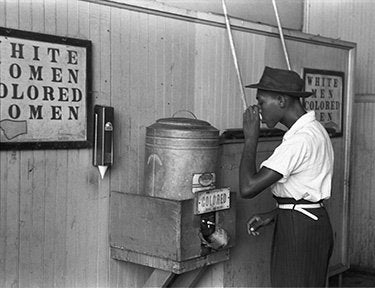

It’s something I always remembered. Inside the medical clinic in my new hometown, there was a plate glass window through which I could see the “Colored” waiting room. The room wasn’t horrible, but it and the furniture in it were not nearly as nice as the waiting room where I was heading. The water fountains were marked “White” and “Colored” as well.

We had just emigrated for the second time, arriving in the heart of Alabama in 1966. It was a different time. Fear of the Klan was real. I once mentioned the Klan to a white friend while standing on street corner, he and turned white as a sheet (pun intended) – warning me never to talk about “them.”

A decade later, when I graduated from college in that same town, the difference in the atmosphere was palpable. Not only had official segregation disappeared, but when a Klan rally was held in a nearby field, several hundred Black citizens gathered to watch the rally. (The police were not thrilled about this, but fortunately no violence resulted.)

You can’t give any particular person credit for these changes, but no one deserves more credit than the Rev. Martin Luther King Jr. His impact came both through the movement he led and his martyrdom. He was one of a number of civil rights leaders who were assassinated, and strange as it may seem, they were only the incidental targets; the real “target” was the morale of the Black population, which the assassins wished to cow. By 1968 this completely backfired, and although King was an enormous loss, if anything his death galvanized his supporters and many moderates.

[adrotate banner=”23″]

The latter was what King and others had been hoping to do, and his frustration at the reluctance of centrist whites to be more receptive to change led him to move toward a more radical position. No surprise – both he and his father were named after the most successful radical revolutionary in Western history, Martin Luther, who launched the Protestant Reformation in 1517.

King, also sharing a doctorate in theology with his 16th-century namesake, certainly understood this. However, his commitment to non-violence drove him to embrace a more moderate approach, and he had evidence that it might work. He knew that Alabama and other Southern states had a far more complex history than is often painted.

Alabama had adopted an anti-Klan law in 1949, long before the Civil Rights movement gained political traction. The law forced Klansmen to remove their masks in public. Voters in Birmingham had expelled Bull Connor, the city commissioner who stayed in office illegally and became infamous by using attack dogs and fire hoses on civil rights demonstrators.

But the forces working against King were formidable. His real problem was not the Klan. The Klan was a group of small, poor, mutually unfriendly organizations widely despised among the public. But deep public attitudes, hearkening back to resentment about the Southern defeat in the Civil War, empowered many enemies.

FBI Director J. Edgar Hoover detested King, whether because of racism or his belief that King was in league with the Communists, is impossible to say. Hoover did whatever he could to undermine King. Opportunistic Alabama politician George C. Wallace used racism as a political weapon – with success. When Alabama Attorney General Richmond Flowers prosecuted the Klan and fought for desegregation, he got so much abuse that his son refused to play football for Alabama, instead heading for Tennessee (Alabama folk will understand the depth of this decision).

I saw some of this first-hand. During my high school years, the pastor of the local First Baptist Church invited the ministers of the small surrounding Baptist churches to come and worship with him at Thanksgiving. These ministers were Black. The Elders of First Baptist dismissed the minister. What happened next was familiar to those who know the history of Baptist churches, but it also showed how things were beginning to change. The deposed minister, along with 40 percent of the congregation (and 60 percent of the money!) promptly crossed town and founded a new Baptist church, which to this day stresses inclusivity as a value. For a small town in the heart of Dixie, it was a big step.

Many steps remain. But at least that plate glass window is gone.

Hubert van Tuyll is an occasional contributor of news analysis for The Augusta Press. Reach him at hvantuyl@augusta.edu

[adrotate banner=”35″]