by Jared Ogden, Sr.

My parents were the only white people to attend Bill’s funeral. It was important to me that they attend. Bill was my friend. I still grieve from Bill’s death 50-plus years ago.

I never told Bill Bonner of my first impression of him. If I had, he would have laughed, and I would have laughed, too. I just returned to Fort Benning for additional training before going to Vietnam. After completing the Officer’s Basic Course at Fort Benning, I was assigned as a staff officer, responsible for transmitting a weekly report to the Pentagon. Staff work does not provide the hands-on training a lieutenant needs for leading a platoon in combat, so I requested a transfer. Instead, the Army offered to send me to Airborne School and Ranger School en route to Vietnam. I accepted the offer.

While I was getting supplies for “Jump School,” another officer checked in. This officer was different. He knew the supply clerk, and the supply clerk greeted him with the utmost respect. The clerk revealed where the newest equipment and best supplies were hidden. I could not see his rank, but from the hardy “Yes, Sirs!” and “No, Sirs!” from the clerk, I assumed he must have held a high position. I overheard him explain that he would finally attend Airborne and Ranger Schools before crossing the Pacific Ocean. As he walked past, I did not look up. Still, I noted that his shoes were perfectly “spit-shined,” and the cut of his uniform trousers conformed exactly to army regulations. He got what he needed, then left. As he was going, I glanced and was astonished that this impressive officer, who I later learned was Bill Bonner, was only a second lieutenant, like me.

Back then, the Army’s work uniforms were called fatigues. They were 100% cotton. At each morning formation, we dressed in freshly washed and heavily starched fatigues and spit-shined boots. On the Monday afternoon of the second week of “Jump School,” I went to the laundry to pick up fresh uniforms. Bonner was in front of me. He mentioned that he had driven home over the weekend. His home was in Augusta, only four hours away. I had gone home to Augusta that weekend, too. We chatted for the first time. He graduated from Aquinas High School, and I graduated from Butler High School. A friendship began. After, Airborne School we enrolled in Ranger School. We were assigned to the same squad. Our squad consisted of 15 Ranger trainees. Ranger School is demanding. In our squad, only 7 of the 15 original trainees graduated. Getting through Ranger School requires grit and teamwork. If a fellow squad member was missing or needed something, we shared.

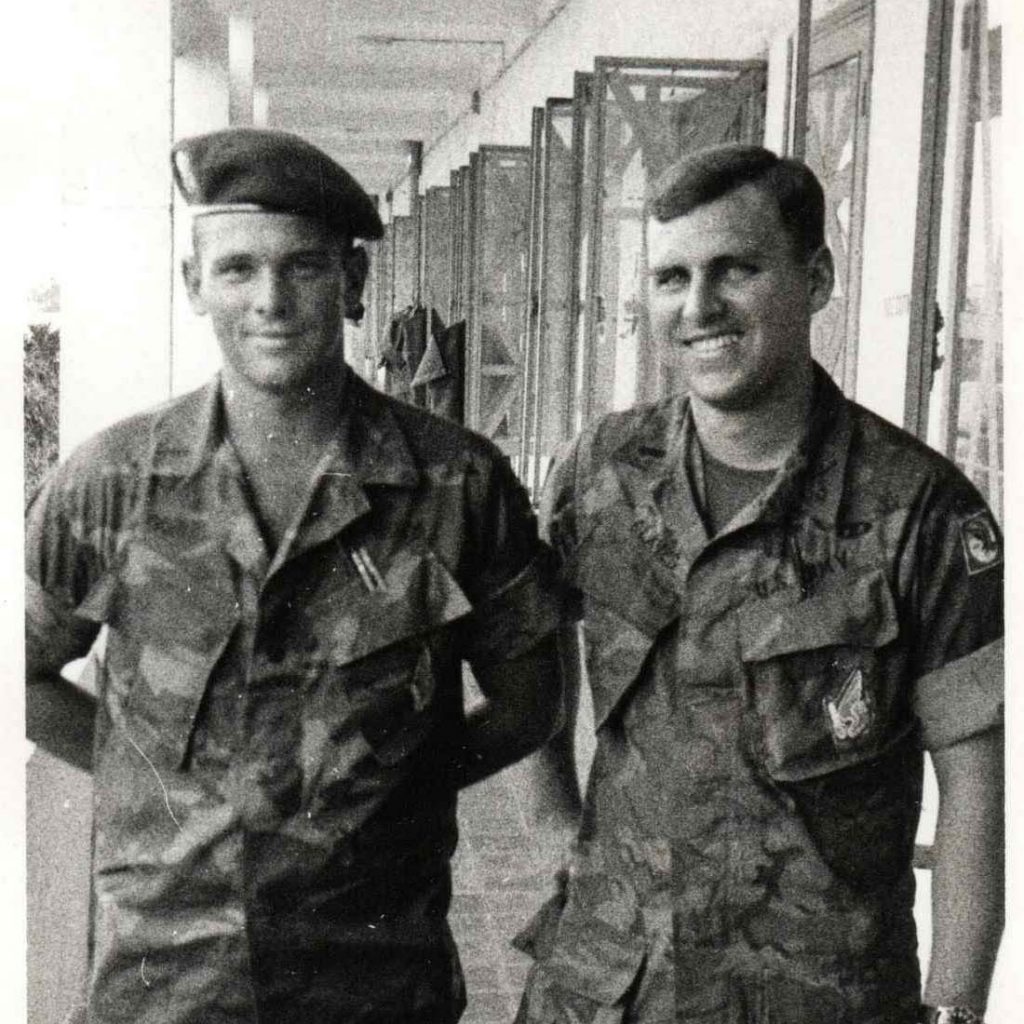

Bill knew that he would be assigned to the 3rd Brigade, 82nd Airborne Division in Vietnam upon Ranger School’s completion. I had no idea where I would be going. Surprisingly, upon arrival in Vietnam, I reported to the 3d Brigade, 82nd Airborne Division. A brigade training school had been established to acclimatize newbies and teach 3rd Brigade policies and procedures. Bill and I were the only officers attending that rotation. Bill and I were assigned the same room.

Again, the friendship and respect continued to develop. We departed for assignments. Bill became an infantry platoon leader in the 1/508th Infantry Battalion. I became the battalion reconnaissance platoon leader in 1/505th. I did not see Bill until President Nixon ordered the brigade home to Fort Bragg. Since neither of us had enough time in-country to return to Fort Bragg with the brigade, we interviewed in other units for positions. As Airborne Ranger first lieutenants with combat experience, we were highly recruited.

We chose to become advisers with the Army of Vietnam Airborne Division (ARVIN ABN DIV.) All soldiers in the division were volunteers and had a reputation as brave fighters. They were credited with preventing the Presidential Palace from being overtaken by the North Vietnamese during the Tet Offensive in 1968.

As new members of the ARVIN ABN DIV advisory detachment, we spent a week in Saigon learning unit procedures and policy. A surprise benefit of being attached was that while in Saigon, we were allocated a Jeep. Since the Airborne Division had soldiers guarding the area all around the Presidential Palace, we were not subject to curfew restrictions. As a result, we could travel anywhere in Saigon any time we wanted to. Our detachment commander had two non-negotiable requirements, (1) that we stay out of trouble during the off-hours, and (2) we complete each morning’s run. The jeep, the curfew exemption, and the knowledge that we would be away from civilization for a long time motivated us to explore Saigon during the evening and early morning hours.

We got little sleep that week, but we got to know each other well. We discussed many topics, but now when I reflect, we never discussed personal long-term plans. For us, those plans were on hold until we completed our tour in Vietnam. For us, a long-term plan meant living to fight another day. I learned that Bill was a man of high moral standards. He was engaged, though I never knew his fiancée’s name. His great-grandfather had been a slave on a plantation near Harlem, Ga.

When the Civil War was over, most former slaves left, but Bill’s great-grandfather remained and helped the owner, a widow, run the plantation. When the owner died, she gave his great-grandfather 400 acres in her will. The land was still in the family, and Bill was the heir. Upon graduating from Aquinas, he was awarded a full scholarship to Emory University. But even with the generous scholarship, money was tight, so he temporally dropped out to earn money to return and graduate. That is when the draft board caught up with him. Testing high, he enrolled in Officer Candidate School (OCS). He never bragged, but he must have finished near the top of his class because he remained at Fort Benning, assigned as a training officer. OCS only picked their top graduates to become trainers. Hence, when I first noticed him in the supply room at “Jump School,” he appeared nearly spit-polish perfect.

The ARVIN ABN DIV consisted of three brigades. The brigades rotated duties. One trained, one guarded the Vietnamese Presidential Palace in Saigon, and one was actively fighting the North Vietnamese Army along the Cambodian border. After our week in Saigon, Bill went to the brigade that was training, and I went to the brigade that was fighting. We shook hands, promised to meet again in Saigon, and departed. I never saw him again.

In less than a month on the Cambodian border, an exploding North Vietnamese rocket collided with my body. The collision occurred at 4:30 in the morning. The first rocket explosion woke me, and moments later, fragments from a second rocket hit me as I rolled out of my sleeping hammock. Once the firefight was over, and I had time to determine that my wounds were non-life-threatening and to help mollify the pain, I thought of the great fun Bill would have relaying to friends how I got wounded.

You see, while we explored Saigon, we discussed the people we knew who had been killed or wounded. Although we knew injury or death usually is not caused by a personality defect, we entertained ourselves by determining the fatal character flaw leading to their battlefield mishaps. While waiting to be taken to the hospital, I enjoyed envisioning Bill entertaining friends with Ranger School’s exaggerated stories. From time to time, to stay awake during lectures, I placed sharp pencils under my chin so when my head dropped while dozing, the pain of the pencil prick would awaken me. I smiled as I imagined him relaying in his deep resonating voice, “Remember how Ogden was always dozing off in class? Well, he got shot out of a hammock—while sleeping!”

Hospitalized in Saigon and just before being sent to Japan for further treatment, I learned that Bill had been ambushed. A machine gun ripped three rounds across his abdomen and chest, hitting his spine. He was unconscious. Later in Japan, I heard that Bill regained consciousness, recorded a message for his fiancée, then died.

After being discharged from the hospital at Camp Zama, Japan, I returned to Augusta. My dad took me to visit Bill’s family. After Bill’s funeral, they wondered who the white people attending were. They recognized my dad and appreciated our visit. I gave the family a picture taken of Bill in our quarters shortly before separating for the new assignments. The picture showed Bill relaxing on a dirty, bare mattress.

Currently, when I think of the picture, I recall that sheets were provided. But Bill and I were field soldiers. Sleeping on a mattress was a luxury enough. Sleeping on sheets was beyond our expectations, so we never made the beds.

His family showed me the Purple Heart and the Silver Star for bravery awarded posthumously. On seeing those cold medals, my mouth dried, my emotions numbed, I could not cry or express the sadness that overtook my soul.

I have visited the Vietnam Wall Memorial in Washington, D.C., several times. I always rub my fingers over Bill’s name, chiseled in the stone. I am overcome with sadness, yet in public, I have never been able to release a cathartic cry. I continue to grieve, especially on Memorial Day, in private, not just for Bill and his family but for the families of other military members whose lives were lost.

Jared Ogden Sr., is an Augusta native now living in Blairsville, Ga. He is a graduate of Butler High School, the University of Georgia and Georgia State. He worked as an accountant in Roswell, Ga., while serving in the Army Reserves, and he served in Operation Desert Shield/Desert Storm in 1990 as a member of the Army Staff in Riyad, Saudia Arabia. He retired from the Army as a lieutenant colonel. More importantly, he was Bill Bonner’s friend.

Resources

Basic information about Lt. Bonner can be found at this website along with two pages of remembrances from family, friends and fellow soldiers: https://www.vvmf.org/Wall-of-Faces/4722/WILLIAM-E-BONNER/

The following is information on Bill Bonner provided at the website for the Vietnam Wall. As with everyone listed on the wall, Bill was so much more.

1LT – O2 – Army – Reserve MACV Advisors

Length of service: 2 years

His tour began on Jul 29, 1969

Casualty was on Dec 27, 1969

In PHUOC LONG, SOUTH VIETNAM

Hostile, died of wounds, GROUND CASUALTY

GUN, SMALL ARMS FIRE

Body was recovered

Panel 15W – Line 97

WILLIAM EDWARD BONNER

Army – 1LT – O2

Age: 22

Race: Negro

Sex: Male

Date of Birth: Sep 13, 1947

From: AUGUSTA, GA

Religion: BAPTIST

Marital Status: Single