(Disclaimer: The opinions expressed in this column of those of the author and do not necessarily reflect those of The Augusta Press.)

“What’s past is prologue.”

“It’s like déjà vu all over again.”

“History doesn’t repeat itself but it often rhymes.”

All famous quotations, respectively from Shakespeare, Yogi Berra and psychologist Theodor Reik (not Mark Twain, alas), suggesting that what is happening now can be better understood by looking at the past.

Nothing new about that idea. Individuals, cultures, and nations change slowly. When the first atomic bomb was detonated, Albert Einstein said that “everything has changed except our way of thinking.” In other words, how we come up with our thoughts, ideas and beliefs does not change very rapidly. This is as true of international crises as anything else.

No event is exactly like another. However, aggression by one state against another, as we see now with the Russian invasion of Ukraine, is nothing new. America opposing such aggression is also not new, although it hardly goes back to our founding.

Instead, it came about toward the end of the 19th century when the United States first started to exercise a significant global role in the wake of the Spanish-American War (1898). That conflict ended with the American conquest of the Philippines from Spain, which plunged us automatically into the affairs of eastern Asia. In particular, we were opposed to the carving up of China into zones of influence, and this placed us increasingly at odds with the Empire of Japan – an argument not resolved until the dropping of the abovementioned atomic bomb. But that’s a whole different story. Where the current crisis in Ukraine and the American past intersect historically is with a program called Lend-Lease.

The Strategic Situation in the 1930s

The 1930s was an age fraught with danger. In 1931, Japan annexed the northeastern part of China. Two years later, Adolf Hitler and the Nazis gained power in Germany. In 1935, Italian dictator Benito Mussolini invaded Ethiopia. In 1937, Japan launched a massive invasion of China. The following year, Hitler annexed his native Austria and then demanded a strategic slice of Czechoslovakia, a demand to which that country’s allies Britain and France capitulated at the Munich Agreement of October 1938. This treaty merely positioned Hitler to occupy all of Czechoslovakia and place him in an excellent position to attack Poland.

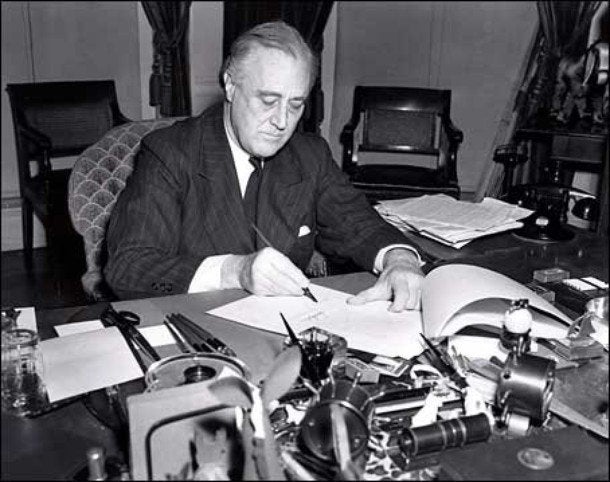

Lend-Lease program. Photo courtesy the Library of Congress.

The Munich Agreement is still cited today as an argument never to engage in appeasement. This is both a dangerous oversimplification, and for Americans, a somewhat questionable point. It’s an oversimplification because it ignores a very basic fact; the British leader thought that, in case of war, he would lose, because there was no public support for going to war on Czechoslovakia’s behalf.

Prime Minister Neville Chamberlain will be forever tied to his unfortunate statement when he came back from Munich – “I believe this is peace in our time” – but he did his best to prepare the country for a war he regarded as inevitable. In other words, he was not trying to appease, but rather to buy time. We know now that he was wrong, that it was Hitler who was not ready; but Hitler thought he was ready – and he was disappointed that Chamberlain gave in!

But that doesn’t matter.

What does matter is the American role in this. President Franklin Roosevelt would have dearly loved to support Britain and France, but he couldn’t. In fact, Congress passed laws known as the Neutrality Acts that would have made it impossible for the British and French to even buy what they needed in America, should war break out – and told them certainly not expect any help.

A powerful movement in America called “America First” argued that our entry into World War I had been a mistake and that we should avoid all such conflicts in the future. Roosevelt understood very well that remaining isolated from world affairs in this way was a pipe dream, but political reality meant that he had to move very, very carefully. Every military expense was challenged on the grounds that it would make our entry into the next war more likely. So, when the 1930s crises were happening, the United States played a largely negative role in Europe, making it more difficult for the British and French effectively to oppose Hitler.

In Asia, of course, the situation was different. The United States still owned the Philippines, as well as a smattering of territories such as Hawaii, Guam and Wake. Our opposition to foreign occupation of China had been American foreign policy since the 1890s. However, there was hardly any chance that Americans would be sent to fight Japan. On the other hand, extremist groups in Japan were demanding that the country establish an East Asian empire to include Southeast Asia, Oceania, and China; such expansion would inevitably lead to conflict with the United States.

And not just the United States – this is what is often left out of the picture when we look at what the British and French were dealing with. At the time of the Munich Agreement, both those countries were increasingly alarmed by Japanese aggression because, like the United States, they had territories in Asia. France controlled Indochina while Britain held today’s Malaysia, Singapore, Burma and India. Further south lay the Dutch East Indies; while the Netherlands was a small power militarily, its colony was extremely resource rich. So, Britain and France, greatly weakened and impoverished by World War I, were now facing major crises on both sides of the world.

The United States and the War, 1939-41

A sobering thought: so many people knew that the crisis was coming, but no one could not stop it. Britain and France both signed mutual defense treaties with Poland, Hitler’s next most likely victim, but that could not stop the war. Hitler, whose forces surrounded Poland on the north, west, and south, signed a treaty with Poland’s eastern neighbor, the Soviet Union, and he invaded on September 1, 1939. Britain and France both did the honorable thing; they honored their treaty obligations and declared war on Nazi Germany. It’s something worth noting. No other major countries went to war by choice against Nazi Germany. And they paid the price. In May-June of 1940, the Nazi armies overran France and a host of smaller north European countries.

This represented a vast change in the global strategic situation. The French army had been named the best in the world by Time magazine. Everybody – and by that I mean the French, the British, the Soviets, the Americans, and yes, even the Germans! – expected the fight for France to be a long one. Everybody’s calculations went down the drain.

That included Roosevelt’s. He had expected that, like Woodrow Wilson in World War I, he could remain neutral as long as he pleased, and then enter the conflict in its last stage. Then he would be in a position to create a new international order to prevent such bloodbaths in the future.

unpacked and checked by an ordnance corporal.

Photo courtesy the Library of Congress.

Now this concept lay in ruins. Britain stood as the only major country opposing Hitler and Nazi Germany. Before long the Nazis would launch an air campaign against Britain, first to destroy its air power, and then opting for the attempted destruction of London.

In America, this had two results. First, it began to lead to a shift in public opinion on the subject of military preparation. The shocking Nazi conquest, supplemented by even more shocking Nazi behavior, and the nightly radio broadcasts from London by people like Edward R. Murrow, started to convince more Americans that we either had to defend ourselves, or possibly get ready to get involved. The draft was instituted. Huge military aircraft production was developed. If there was one major difference between America in the two world wars, it is this: we were ready for World War II.

The second result was what connects this era to what we are doing in Ukraine. Roosevelt realized that American military preparations would be highly beneficial in the long run, but there was a more immediate problem. Britain stood alone. If Britain collapsed, the Axis conquest of Europe would be complete, and the United States might find itself isolated and overpowered.

So, Britain had to survive. But how? A military entry into the conflict was politically impossible. In the short run, the American government arranged for financial assistance in the form of loans, as a British financial collapse could have ended its war effort. However, something bigger was needed, and a way forward was found.

What was found was the Lend-Lease program. Under this remarkable program, the president of the United States could give any foreign country “resisting aggression” both military and civilian supplies – everything from boots to bombers. This program, established in March of 1941, would allow the United States to remain neutral but still prop up Britain – and eventually extend the same support to a host of countries, the Soviet Union included. We’re not talking small gestures. In today’s dollars, Lend-Lease aid was about $755 billion.

How was this massive transfer of material and supplies accepted in America? Several arguments were made to convince the American people and their representatives of its value. First, it would enable us to remain neutral. Technically, we could do so because we never had to even name the aggressor; the president only had to designate that a country was suffering aggression. No declaration of war was needed. This argument was obviously history just a few months later, but in the meantime, the administration pointed out that arming others was a cheaper alternative in blood terms to doing all the fighting ourselves. (True, that.) Finally, Lend-Lease was a remarkably clear way to harness America’s industrial might to the global war effort, especially as it would be late in the war before we could come directly to grips with all the Axis forces.

One other – but rarely used – argument was that the equipment was being “lent” or “leased” so that in theory it would be returned, or paid for. Roosevelt certainly had no intentions of collecting any money for Lend-Lease. He viewed it as a way of keeping allied armies in the field and also supporting allied industries with specialized materials and machines. (My wife, THE AUGUSTA PRESS executive editor Debra Reddin van Tuyll, has suggested that my whole dissertation on Lend-Lease to the Soviet Union was basically counting boots. It wasn’t, but in case anyone cares, we did send 14.793 million pairs of boots to the Red Army. We did not ask for the boots to be returned.)

So, what does this have to do with the attack on Ukraine? Aren’t there differences? Of course. The United States had made very clear its position even before the invasion. In addition, the United States has acted as part of an alliance (NATO) and has also received UN support. (Very appropriate, as the UN began life as the anti-Axis alliance in World War II.)

But once again, the United States has searched for ways to assist a country facing aggression, and once again Congress has appropriated money to aid the victim country. We have been this way before.

Hubert van Tuyll is an occasional contributor of news analysis for The Augusta Press. Reach him at hvantuyl@augusta.edu