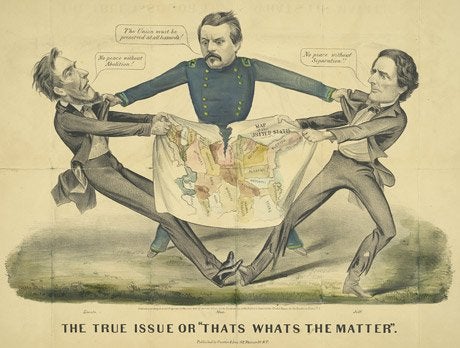

Were Confederates traitors? It’s a hot-button question all of a sudden – but not for the first time.

At the outbreak of the Civil War, those who supported the United States (which included a fair number of folk in the Southland) were quick to label the rebels as traitors, and that insult did not disappear during the war.

After Fort Sumter there wasn’t much talk anymore about Southerners and sedition, which only involves inciting rebellion against the country; once the conflict became a real war, or to use the legalese – once Southerners were “actively levying war against the United States” – that word game was no longer necessary, except during election campaigns in the North.

Either Southerners were traitors from the beginning or not at all, so we will start our analysis with South Carolina, our beloved neighboring state where so much history has been made, both good and bad.

South Carolinians held the first state convention that adopted the first ordinance of secession. It might have been interesting if the Carolinians had first asked the Supreme Court for an opinion on whether secession was constitutional, but instead, those who voted at the Palmetto state’s convention opted to act on the basis of their own interpretation of state “sovereignty.”

A sovereign state may always withdraw from an agreement. However, the concept of state sovereignty, while enshrined in the Articles of Confederation, had been abolished with the ratification of the U.S. Constitution. True, John C. Calhoun disagreed, and while I concede that he was indeed brilliant, he was also a bit eccentric, and his view was decidedly a minority one—and caused quite a rift with President Andrew Jackson, a staunch Unionist, under whom he served as vice president.

The states CAN dissolve the Union, but only with ¾ agreement.

Advocating unilateral secession was not treason, but it might have been sedition. However, the question became null and void on the night of April 12/13, 1861, when the heavy guns of Charleston opened fire on Fort Sumter.

The forces lobbing shells at Fort Sumter were Confederate, but the pressure to act came from South Carolina itself. We may well ask why. True, South Carolina claimed the fort as part of its territory, but its existence hardly threatened either the Confederacy, or even Charleston – except in its pride. And some historians do agree pride was at the heart of South Carolina’s actions — and sex. South Carolina Gov. Francis Pickens was 27 years older than his wife, a renowned Southern beauty and the only woman to appear on Confederate currency. Some believe Pickens forced the confrontation at Fort Sumter to impress his wife.

The Confederate government in Montgomery more permitted than insisted on the Fort Sumter attack, for which Pickens and other South Carolinians had pushed so hard. In my opinion, the decision to fire on Fort Sumter was the worst military decision of the 19th century, and I include the (in)famous Charge of the Light Brigade in that comment. The shooting inflamed the North, where many people had been willing to see the Southern states depart peacefully. Now, with Southern guns firing on the United States flag, the Confederates were labeled as traitors.

But were they?

Certainly, the Southern soldiers had attacked a federal installation, and South Carolina and most of the other Confederates had seceded by April 1861. Further, the charge of treason against the rebels was a HUGE motivator among Union soldiers and civilians alike. However, there are two problems with the ‘traitor’ label.

The first problem is that no one Confederate was ever tried in court for treason. Two were executed for war crimes and more for espionage, but even the president and vice president of the Confederacy were never put on trial.

The reasons for the lack of prosecutions are complex. Washington was in absolute chaos, especially with the assassination of Lincoln; it is a small miracle that act did not trigger a campaign of vengeance against the South.

The Radical Republicans, who would have been most likely to demand trials, were more interested in the powerful plantation owners who had led the South to secession and war, than the soldiers who had done the fighting. They, in turn, were checkmated by the new president, Andrew Johnson, who, despite his professed hate for the Southern upper class, issued some 14,000 pardons, effectively blocking federal justice.

After that, the main political battle became the Republicans versus the new president. One other issue is often forgotten: what would the outcome of such trials have been? Doubtless, Confederates would have gone all the way to the Supreme Court, and what if the Court had decided that the rebels had been right, even in part? So, both sides had good motivations to avoid the courts; the Confederates risked hanging, the Unionists risked the validity of their cause.

The second problem has to with intent. All criminal law is based on the combination of the act and the intent. For most crimes, the intent may be presumed, although rebutted. If you shoot someone dead, the state may try you for murder; but you might be able to prove that it was an accident, in which case you would be guilty of a lesser charge.

Some crimes, such as ‘hate crimes,’ specifically require evidence of intent. With treason, this is tricky. On the one hand, the Confederates took up arms against the United States government, and that by itself was enough to convict. The law would need no more. But we, looking back historically, are not bound by the legal technicality, and can consider the mindset of the Confederates.

When Southerners attempted to secede and then waged war, what were they actually thinking? They did not believe that they were abandoning America. Instead, they thought that they were creating a new, more accurate version of America, which is obvious in two actions the Confederates took. First, the name of the new country was only one word different from the original. Second, the constitution they wrote was remarkably similar to the one they had just abandoned, apart from the new references to slavery and a six-year presidential term. In other words, the Confederates believed that they were the real continuation of America.

So were they traitors? In 1776, our Founding Fathers knew and acknowledged that their behavior then was treason under existing law. In 1860-61, the new Confederates sincerely believed that they were not traitors. This would not have saved them in a court of law, but perhaps the historical verdict will be kinder.

Hubert van Tuyll is an occasional contributor of news analysis for The Augusta Press. Reach him at hvantuyl@augusta.edu