Can America survive? It depends on what we mean by “America.”

There will always certainly be some kind of country in our neck of the woods. But what kind of country? When people say “America,” they mean more than a place; they mean a set of ideals that we either are or should be living to. In particular, we think of our country as one enjoying the rule of law, not governed by either a despot or by a mob.

America is a democratic republic. It cannot exist without the rule of law. It’s not for nothing that we hear about so many court cases and have so many lawyers. Once upon a time, we taught our children that we were “a government of laws, not men,” and while that might have been a tad optimistic, it summarized some of our most basic beliefs.

Yet nothing lasts forever. There are definitely forces that are undermining the American system. If these forces were unique to America, I would not worry too much, but they are global. To modify a great saying, no country is an island. What happens out there and what happens here are not separate. It’s been that way for centuries, incidentally. It’s just more obvious now. Think about D-Day, of which we recently celebrated the anniversary. It was the second time that a generation of our young men went to fight in France, and both times against somewhat similar forces.

We have seen a global rise in extreme nationalism. What is extreme nationalism? Let’s keep it simple; it’s ordinary patriotism that is taken way too far. There are usually some myths about the national past, a disdain for all other countries and cultures, an attitude that only our interests should be taken into account, and a strong tendency toward authoritarian government led by a charismatic leader. More about that in a moment.

[adrotate banner=”19″]

There are two things we should know about extreme nationalism. First, it has surfaced in various forms in an astonishing number of countries. China, Russia, Myanmar (Burma), Japan, Turkey, Poland, India and the United States are just a few of the countries where extreme nationalist movements hold or have recently held power. Similar movements have gained a substantial following in France, Germany, and Spain. Israel is in flux, and Britain is a close call. And these are just a few examples.

Second, extreme nationalism played a big role in bringing about both world wars. Extreme nationalists are not likely to consider the interests, views, or positions of foreign countries. Treaties and negotiated settlements are not popular. This is also why modern extreme nationalists attack foreign aid. They also tend toward militarism, that is, an excessive glorification of everything military. In other words, if you glorify your own nation at everybody else’s expense, and insist that all your perceived national interests must be accepted by all other countries, eventually the only alternative is war.

You might say so what; after all, we won the last two world wars. But that’s not what I’m here to talk about. In the immediate future, the problem is that fanatics do not accept the rule of law. This is not just true of extreme nationalists. At the other end of the spectrum, communism does not accept the rule of law, either. Law, by definition, is a barrier for those who desire truly radical change, as this usually requires changing a whole country’s constitution. This is not easy in any country where constitutional rule has truly existed long enough to be accepted by the whole nation. And here is where it gets scary.

For most of its history, the U.S. Constitution has enjoyed a quasi-religious acceptance. Consider two examples. When a group of southern states attempted to create a separate republic, they wrote a constitution that was nearly the same as the one from which they were departing. So, like an amoeba, the United States briefly split into two separate constitutional republics, and then one was reabsorbed by the other. During the Great Depression, President Franklin D. Roosevelt proposed “packing” the Supreme Court by adding seats to it, which would have given him the chance to appoint more justices. Yet even in the midst of our worst economic crisis, there was massive resistance. Millions thought this was an attack on the constitutional balance of power, even though the Constitution does not specify the size of the Court.

[adrotate banner=”22″]

This attitude toward the Constitution is slipping. While it is slipping more on the right than the left, one can see signs of it on the left as well. Recently there were calls inside the ACLU for the organization to stop representing far right groups in free speech cases. The “1619 Project” proposes a negative vision of the nation, which inevitably would take our respectful vision of the Constitution — and the men who created it — into the dustbin of history. This is dangerous on many levels.

If the Founding Fathers and their handiwork becomes nothing more than another historical curiosity, this country could become extremely unstable, especially as our political parties become increasingly unmoored from their traditional perspectives. For example, earlier this year, the Democratic Party renewed calls to “pack” the Court. President Biden, fortunately, dealt with those calls by appointing a commission to study the issue (a guarantee that nothing will happen).

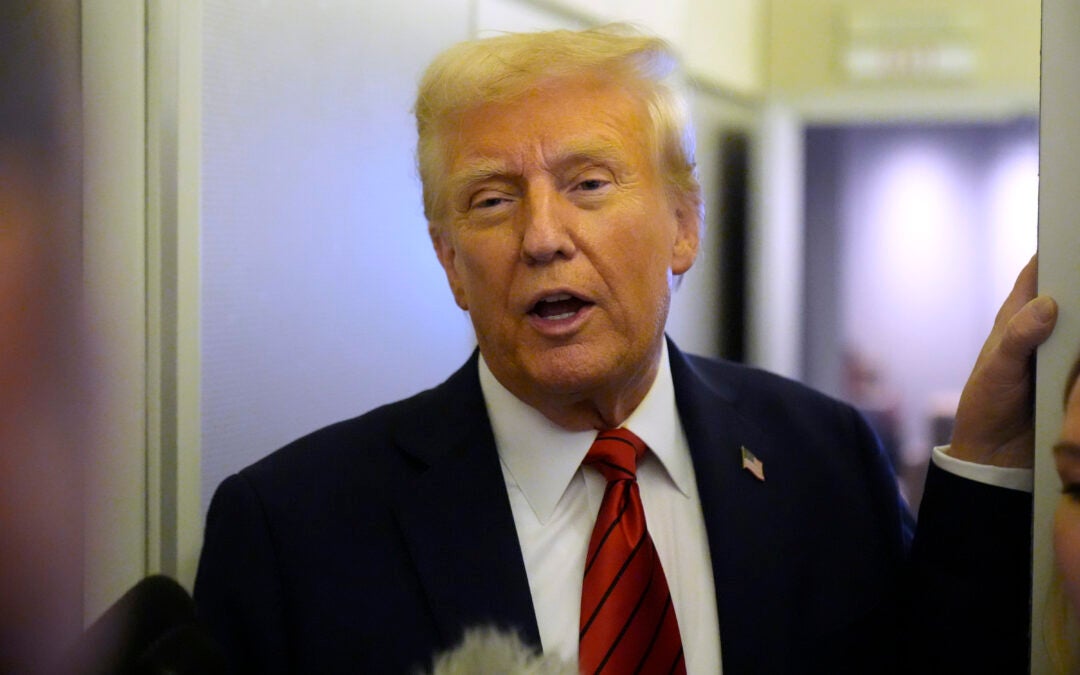

But a far greater threat exists than arguments about how many justices should sit on the Supreme Court. If the rule of law is merely considered an impediment, what will be the alternative? We already know, and it isn’t good: dictatorship. The extreme nationalist movements in Europe after World War I promoted one-man leadership. We are seeing this happening again around the globe, especially in Russia, China, Turkey, and the United States.

These are examples of countries where a single leader either controls, or is slavishly worshipped by, a single political party. As those parties are tools of a glorified leader, they accept no opposition as legitimate. (Therefore, they do not really accept a free press either.) In countries where there IS an opposition, that opposition will sooner or later develop the same attitude toward the party in power. We came close. Many Democrats wanted to nominate Bernie Sanders, but the majority opted for Biden, a respectable but boring politician whose personality was such a marked contrast to Donald Trump’s that that may actually explain his victory.

[adrotate banner=”54″]

So, does that mean that the threat of extreme nationalism has passed? Hardly — ours is merely one corner of a global trend. And there’s more. Over the last half century, the United States has experienced a decline in the economic middle class, and with it, a decline in mobility. Mobility means the frequency with which people rise in wealth or income. Why does this matter? Because democracy and rule of law develop and thrive wherever there is a strong middle class, not where it is absent. It’s easy to see why. The rich and powerful don’t especially need the rule of law; the poor don’t particularly want it.

But here’s the good news; we’re not doomed.

The polarization between right and left is nothing new. Truth is, we’ve been insulting and denouncing the other side pretty much since the beginning. In the election of 1800, John Adams compared Thomas Jefferson to the Antichrist. And you thought modern negative campaigning was bad!

The habit of listening only to media that say what we like and agree with is actually pretty traditional. Before the 20th century, newspapers were openly partisan and catered to people who shared their perspectives. In fact, newspapers back in the good ol’ days were often founded to share a particular viewpoint with the public.

MORE: Convention of the States?

Plenty of people are organizing to preserve our traditional political values. The ACLU might be wobbling — as are many on the left — but you have new organizations, such as the Foundation for Individual Rights in Education (FIRE), that fight for free speech in colleges and universities on behalf of students and faculty all across the political spectrum.

And finally: we’ve survived a lot. Our first Constitution collapsed in ruins. Our first foreign war was an embarrassment. We fought the bloodiest war in our history against ourselves. In the 20th century, we experienced two world wars, the Great Depression, and the struggle for civil rights for all; in fact, we are still coping with the legacy of slavery and Jim Crow. I remember Vietnam and Watergate as if it were yesterday. Yet that was half a century ago… and we’re still here.

But not by accident.

Eternal vigilance truly is the price of freedom.

Hubert van Tuyll is an occasional contributor of news analysis for The Augusta Press. Reach him at hvantuyl@augusta.edu.

[adrotate banner=”48″]