As school children, we all learned that the Revolutionary War started in 1775, and the founding date for the United States is 1776. We also learned to refer to George Washington as the father of our nation, but he didn’t become president until 1789. So, who ran things in the interim?

To answer that question, we have to consider that the system of government through the war and first years of nationhood was a bit different from what the Constitution gave us when it was ratified in 1787. After the war and before the Constitution was ratified, the United States operated under the Articles of Confederation, which provided for a weak central government and no executive or judicial branch.

Until the Articles of Confederation were adopted in 1781, the Continental Congress was the chief governing body for the fledgling United States, and its president was the highest-ranking office-holder in the country. After the Articles were adopted, its President was the highest ranking officer.

In both instances, the president’s job, though, was much closer to that of the speaker of the House of Representatives. Still, if the buck stopped anywhere, it would have been on the Congressional president’s desk. Consequently just for the sake of digging into a bit of arcane American history, we can consider the 14 men who served as presidents of the Continental Congress and the Confederation Congress as the rough equivalent, at least in rank, of today’s chief executive.

The first of those men was Peyton Randolph, a Virginia lawyer. Before becoming president of the First Continental Congress, Randolph served as a member of the Virginia House of Burgesses and as the state’s attorney general.

He was unanimously elected to the office of Congressional president, and he served two terms. Ill health forced his resignation in 1775, and he died later that year while dining with Thomas Jefferson. His death was due to a cerebral brain hemorrhage (brought on, I suspect, by over exposure to pure intellect).

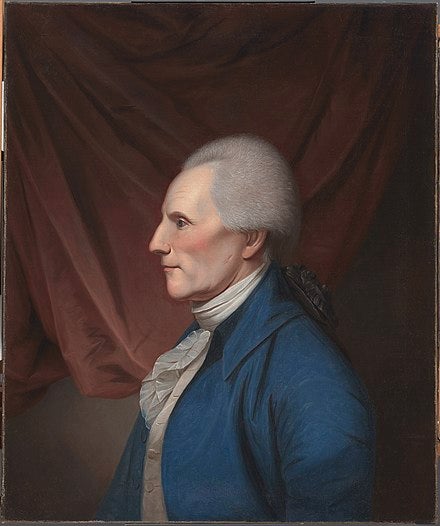

South Carolinian Henry Middleton stepped in as the second president. Middleton was one of the largest landowners in South Carolina. He owned some 50,000 acres near Charleston, and he held some 800 slaves, according to an article about him in the Dictionary of American Biography. Before the revolution, he served as a justice of the peace and as a member of the Commons House of Assembly.

Middleton, a delegate to the first Continental Congress, served as president after Randolph fell ill. Like many in South Carolina, he opposed declaring independence from Great Britain and resigned from the second Continental Congress just a few months before the Declaration of Independence was adopted. He returned home, and in 1776, he and his son Arthur served on the committee that wrote a temporary constitution for South Carolina. Middleton was captured during the Siege of Charleston and accepted becoming a British subject again, according to the South Carolina Encyclopedia. Because of his history as a patriot, he wasn’t penalized as so many Loyalists were after the war.

John Hancock, probably the most familiar name of all 14, served as the third president of the Continental Congress. Graduating from Harvard at age 17, Hancock worked as a young man in his family’s mercantile business, according to the National Constitution Center.

Hancock was among those who took part in the Boston Tea Party, and he also duped the British into believing 10,000 armed colonists were ready to march on Boston if they didn’t evacuate the city. During the war, he helped organize the navy and raised money to pay for the war.

Hancock was named president when Middleton declined permanent election to the position in 1775, and he served until 1777.

Hancock was still president of the Continental Congress when the Declaration of Independence was adopted. According to legend, Hancock put such a large signature on the document so that King George III could read his name without putting on his glasses.

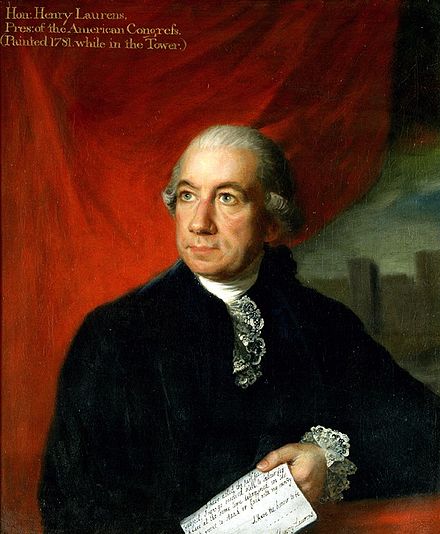

Fourth president was Henry Laurens. He served in the second Continental Congress from November 1777 to December 1778, and was one of the men who signed the Articles of Confederation. Laurens was a rice planter, merchant and slave trader who owned the largest slave trading house in North America.

In 1780, he was commissioned to travel to Holland to negotiate a treaty and a loan, but he was captured by the British Navy and taken to London where he was imprisoned in the Tower and sentenced to be beheaded as a traitor, according to an article about him at the Library of Congress’ website. Laurens served 14 brutal months and was finally released in exchange for Lord Cornwallis during a prisoner exchange after the Battle of Yorktown. He would serve as one of the diplomats who negotiated the Treaty of Paris, which officially ended the Revolutionary War.

John Jay, the New Yorker who would become the first chief justice of the Supreme Court, was the fifth president of the Continental Congress. He served from December 1778 to September 1779. Author of five Federalist Papers, he was the first secretary of foreign affairs (equivalent of today’s secretary of state). Jay also was a slave owner, though he did succeed in getting a gradual emancipation bill passed during his term as New York governor. He also founded the New York Manumission Society. Jay had freed all but one of his slaves by 1810, according to that year’s census.

Samuel Huntington was elected sixth president of the Continental Congress in 1779. He was said to be a brilliant legal mind despite being entirely self-educated. The Articles of Confederation became the ruling law during his term, so some historians refer to Huntington as the first president of the United States. Huntington died in 1796 while serving as governor of Connecticut.

Thomas McKean served as the seventh president of the Continental Congress from July to November 1781. A Pennsylvania native, he moved to Delaware to study law, and he represented that state in the two Continental Congresses. Interestingly, McKean was a Delaware congressman at the same time he served as chief justice of the Pennsylvania Supreme Court. McKean was a signer of the Articles of Confederation.

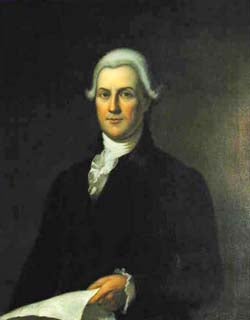

The eight president of the Continental Congress and the first to serve a full term under the Articles of Confederation, John Hanson was a Marylander. Hanson retired from public life after his term as president.

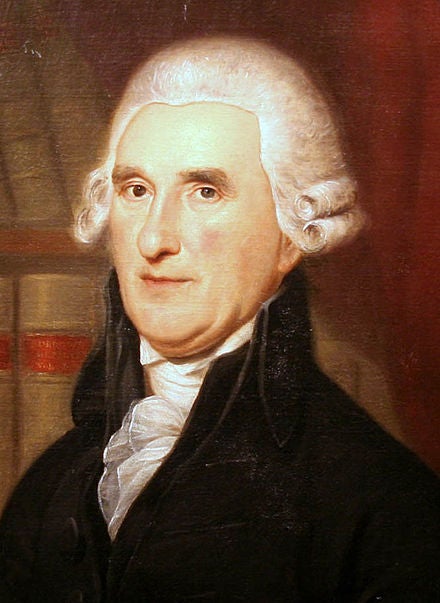

Elias Boudinot was the ninth president of the Continental Congress. He was born in Pennsylvania and grew up as a neighbor of Benjamin Franklin’s. Boudinot helped financed the Revolutionary War and also supported the work of American spies during the revolution. He served as director of the U.S. Mint from 1795 to 1805. According to the Museum of the American Revolution, Boudinot was an advocate for women’s rights and led a campaign in 1793 to encourage women to participate in New Jersey state politics. Boudinot founded the American Bible Society in 1816 and served as its president until 1821.

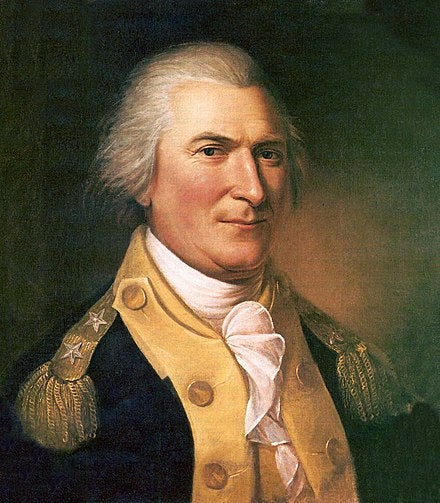

The 10th president was Thomas Mifflin, a Pennsylvanian who also served as a major general and the first quartermaster general in the Continental Army and a delegate to the Constitutional Convention. Washington lost confidence in Mifflin, though, in a controversy over money management in the quartermaster’s corps, but Mifflin would be the man to whom the great general delivered his resignation in 1783.

Richard Henry Lee was the 11th president of the Continental Congress. A Virginian, Lee had protested the 1765 Stamp Act, was a member of the committee that named Washington commander-in-chief of the Continental army and also was the Congressional delegate who introduced the motion that resulted in the Declaration of Independence. The resolution read, in part, that “these united colonies are and of right ought to be free and independent states.” He called for a declaration of independence, the formation of foreign alliances and

a plan for confederation,” according to the document, which is available at the National Archives website. The Continental Congress created three committees to study each of Lee’s proposals. Action on the latter two was postponed until the fall, but members approved the call for a declaration of independence on July 2, 1776.

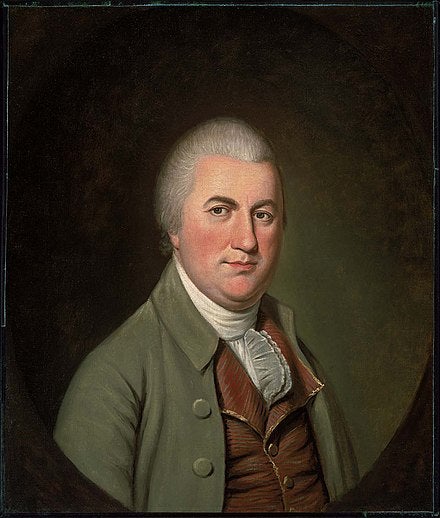

The 12th president was Massachusetts businessman Nathaniel Gorham who was elected when John Hancock could not fulfill his second presidential term. He served from 1786 to 1787. Gorham was a signer of the Constitution. Gorham was among the first to oppose the British during the Stamp Act Crisis in 1765.

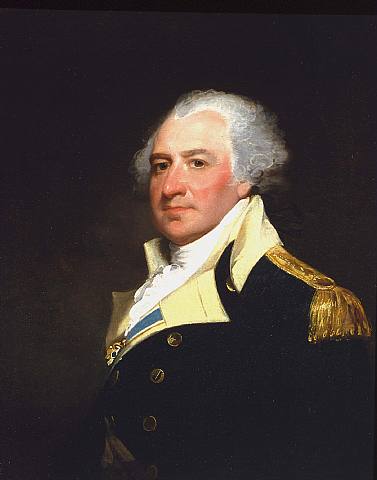

Arthur St. Clair served as the 13th president and presided over the Confederation Congress. Born in Scotland, he was the first governor of the Northwest Territory. A military man, St. Clair came to America as a soldier in the French and Indian War. He resigned his commission in 1762, and by the mid-1770s, St. Clair thought of himself as more American than British. Following the Revolutionary War and his time in the Northwest Territory, St. Clair was commissioned a major general and named commander of the U.S. Army.

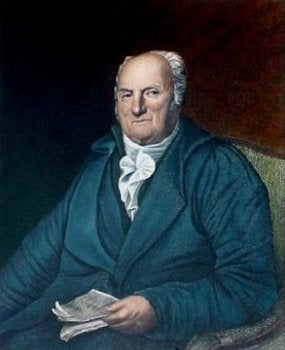

Finally, the 14th president was Cyrus Griffin of Virginia. A protégé of George Washington, it was during Griffin’s term as president that the Constitution was finalized. He served as president from January 1788 until Washington was inaugurated in 1789. Washington appointed Griffin the first U.S. district judge in 1790 and served until his death in 1810. Griffin served on the U.S. Court of Appeals, and in that capacity was one of the judges who presided over Aaron Burr’s treason trial.