I. THE QUESTION

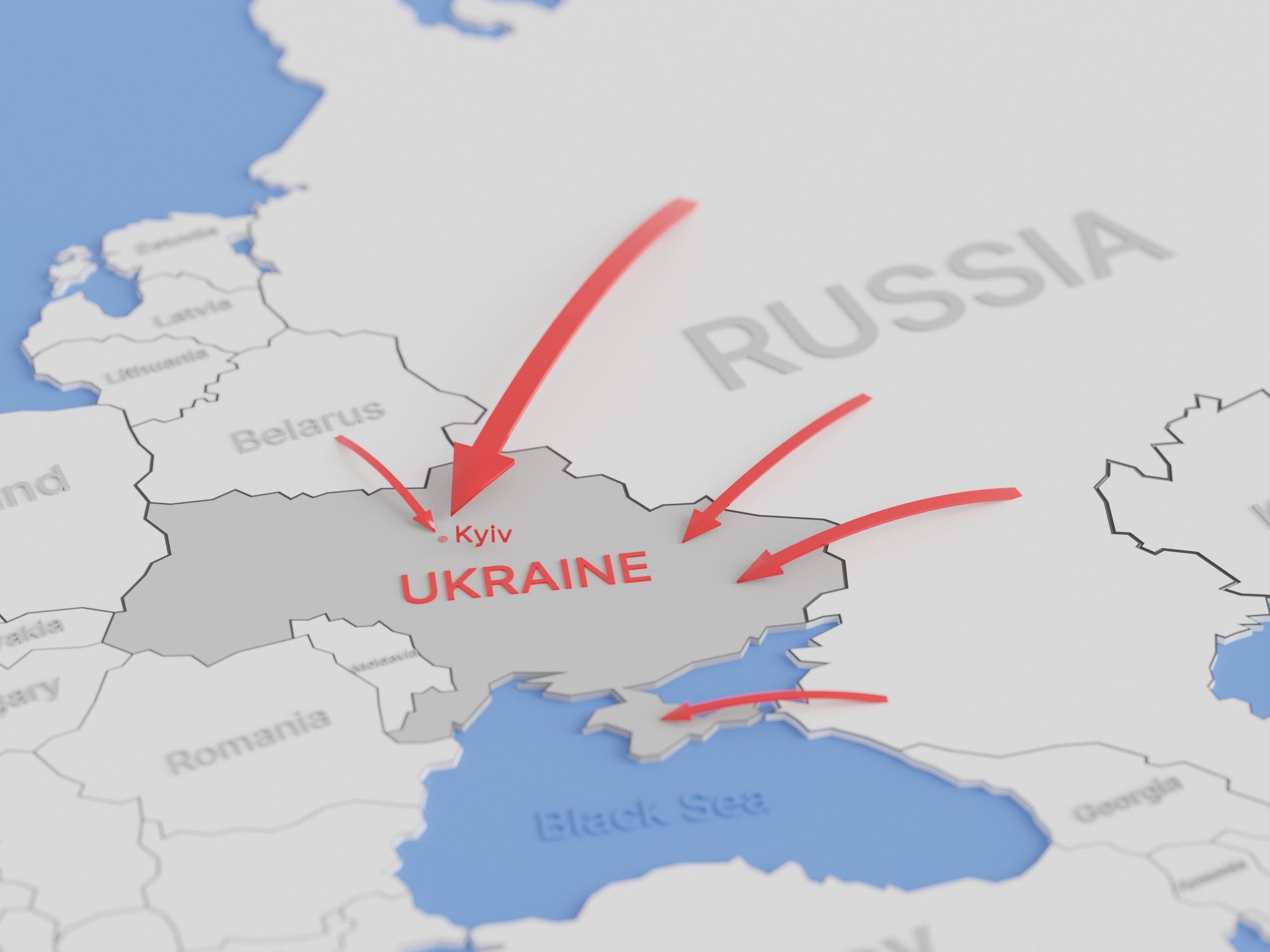

We are only a few days away from the war in Ukraine being a year old. On Feb. 24, 2022 the Russian forces invaded their Slavic neighbor, after years of lower-level aggressions. A border dispute was now Europe’s first large-scale war since the Nazis surrendered on May 7/8, 1945.

The United States is up to its strategic neck in the conflict, coordinating the allies’ responses and supplying billions of dollars in weaponry. But why? Why are we so deeply involved in a country with which we have no direct official alliance? Let’s explore how we got here, and then look at whether we should be.

Opinion

II. GEORGE WASHINGTON’S TEACHING

In 1797, George Washington stepped down after two terms as the first president of the United States. In his “farewell address” (actually a newspaper column), Washington warned his countrymen against “entangling alliances,” urging the young republic to have trade relations with foreign countries only, avoiding strategic and military ties. Washington was preaching to the strategic choir. None of his fellow Founders had any appetite for getting involved in the wars between European powers. This was not cowardice or pacifism – they had just fought an eight-year war for independence. It was pragmatism.

The United States back then was, strategically speaking, a contradiction. On the one hand, we were invulnerable to foreign conquest. By Washington’s retirement, our country occupied 865,000 square miles. Today, Britain, France, Italy, Spain and Germany together live on 753,000 square miles. That alone made the idea of invading and conquering America an absurdity – and I have never found the slightest evidence that any country ever thought about it.

But, paradoxically, our new republic was incredibly vulnerable, as our next major war would show. Most of our people and our wealth was concentrated on the coast. Defending almost 1,600 miles of coastline would require either a massive navy, which we could not afford, or an immense army, which nobody wanted. Fortifying every possible point of attack or invasion was impossible. In addition, there were two strategic reasons to avoid foreign conflict. First, the United States could not “win” in any real sense, because the enemies would be far away and beyond our military reach. Second, we had no need – no potential gain – from foreign wars. Fortunately, the European states recognized all these factors, and none sought American participation in a European war, until the 20th century. American was safely isolated, and isolationist.

But, as the cliché goes, times change.

III. TIMES CHANGE

By the late 19th century, America was becoming an immense industrial power with increasing global interests. American became more connected to the rest of the world, both through economic ties and because of the immense immigration that took place at the turn of the century. But two events in particular changed our historic trajectory. First, there was the Spanish-American War (1898), which led us to acquire Guam, Puerto Rico, Cuba (effectively) and the Philippines, the latter after a bitter counterinsurgency war. This plunged us into the heart of Asian power politics and would lead eventually to Pearl Harbor. The second and much larger event was World War I (1914-18). The United States entered the war in 1917 and would send two million soldiers to fight in France, an overseas commitment without parallel up that point.

Afterwards, there was a major backlash against this burst of internationalism. Many Americans came to believe that our participation in the war had been a mistake and that we needed to return to our isolationist traditions. This was stimulated by lurid conspiracy theories, including one that the whole war had been brought about by machinations among munitions manufacturers. A congressional investigation even concluded such.

This was not without its effects. The Great Depression drew no support for international cooperation here, but instead led to economic isolationism. This was one reason the Depression lasted as long as it did. But more importantly, it led to great public pressure in the 1930s to stay out of the developing strategic crises. These took place on both sides of the world; in Asia, Japanese expansion began in 1931, and in Europe, with the accession to power of Adolf Hitler in 1933. American lawmakers, influenced by isolationist groups such as America First, passed the Neutrality Acts, which would have made it impossible for Britain or France to even buy what they needed in case of war with Germany. Needless to say, French and British efforts to secure military alliances were Dead On Arrival.

IV. APPEASEMENT

This all has to be remembered when we look at what really is the most important thing when deciding what to do, and it takes us to the concept of appeasement. It’s considered a four-letter word in so many circles that we have to consider why it was attempted in the 1930s. In 1936, Adolf Hitler began a series of steps to test Anglo-French resolve to stop him, culminating in his 1938 demand for a slice of Czechoslovakia, known as the Sudetenland. At the Munich Conference in 1938, France and Britain agreed that Hitler could have this territory, on condition that he go no further. We all know how well that worked. Appeasement became a dirty word; American leaders frequently cited its failure as a justification for involvement in crises around the world. It was specifically cited by President George H. W. Bush during the first Iraq war of 1990-91, for example.

Trouble is, vilifying appeasement in EVERY situation overlooks a few things.

First, the British and the French faced a huge conundrum. They were strategically weaker than they had been before World War I. There was no more Russian alliance. The United States would not support them, and they might not be able to even buy what they needed. Public support for war was very uncertain. They really had no solutions. Nor were they naïve about Hitler. The much-denounced British Prime Minister, Neville Chamberlain, ordered maximization of military aircraft production as soon as he got home.

The other, broader problem with denouncing appeasement in every situation is this: you have to consider who the enemy is and what the enemy actually wants. Here, I have to get into a bit of semantics. Sorry! But when teaching, I would write the sentence, “It was wrong to appease Hitler” on the board and ask students to think it through. I would then rewrite it in two different ways, emphasizing a different word each time:

It was wrong to APPEASE Hitler

It was wrong to appease HITLER

The real problem was not so much appeasement but rather that Britain and France were dealing with an unappeasable adversary. (And all criticisms of those two countries should always be measured against an important reality: they were the only two countries that voluntarily declared war on Hitler’s Third Reich. We didn’t. The Soviets didn’t. The British and the French did.)

V. LEARNING FROM DISASTER

Of course appeasement in 1938 failed; Hitler launched his unlimited war of aggression in 1939; the Japanese, with more limited aims, had been attempting to overrun China since 1937. Six years of war and perhaps 75 million lives later, the war ended. America had endured an expensive lesson in globalism. The combination of the Great Depression and World War II taught us that, despite our oceanic borders, we were not isolated. The great Christian poet and cleric John Donne became famous for the line, “No man is an island …” The 30s and 40s taught us that no country is an island either.

Our response was massive. To avoid another economic crisis, we founded the World Bank and the International Monetary Fund. To avoid World War III, we swung from no alliances to countless ones. The most important was and is the North Atlantic Treaty Organization, or NATO. Intended for European security, it was created in 1949 to, the saying went, keep the Soviets out, the Americans in, and the Germans down. This is the alliance whose position we are trying to protect by assisting Ukraine in its defense.

VI. SHOULD WE?

But why? It is a dangerous role for us. It brings us closer to conflict with a great nuclear power. The United States is overstretched. Despite our massive military budget, it is not clear whether we can respond to threats in Europe, Asia and the Middle East all at once – but we could easily find ourselves in that situation. As Ukraine is not a NATO member, we could all sit back and let Putin gobble up Ukraine. After all, Ukraine used to be under Moscow’s control. Can’t we just assume that all that Putin wants is to regain the territories of the Russian Empire/Soviet Union?

We could, but the result might be even more dangerous. Ukraine is (or was) a large neutral country between the boundaries of Russia and NATO. A longer border between Russia and NATO could give Putin even more opportunities for expansionist moves, this time at the expense of NATO members. If that should happen, we would be automatically involved – we are required to provide military assistance to our NATO allies – and assuming that this would NOT lead to nuclear war strikes me as pollyannish.

If we could be reasonably certain that all Putin wants is to reabsorb the old empire, we could stay uninvolved. But such assumptions are inherently dangerous. Furthermore, they do not accord with his behavior, which borders increasingly on the irrational. When he was a KGB officer, his superiors thought him too prone to take risks. He ignored a slew of governments that told him invading Ukraine was not acceptable. Josef Stalin, homicidal psychopath that he was, would have never done something this risky. (He also tried appeasement with Hitler, with phenomenally disastrous results.) It is worth noting that Finland, a country that has had a close if not always comfortable relationship with Russia responded to the Ukraine invasion by asking for NATO membership. In other words, the European country that for many decades was the most trusting of Russia no longer trusts it now that Putin has shown his true colors.

Appeasement works if you are trying to buy time or if you can trust the other side to have limited aims.

Neither applies here.

Hubert P. van Tuyll is a former lawyer and a retired Augusta University history professor. His Ph.D., from Texas A&M, dealt with the American Lend-Lease program to the Soviet Union during World War II.