The COVID-19 pandemic appears to have produced at least one good outcome: many fewer cases of flu this year than in previous years.

Historically, flu has been the biggest annual infectious disease threat for the United States, but not this year.

The number of cases of flu in the United States is way down, according to an Augusta University infectious disease specialist Rodger MacArthur.

Flu this year has been “sporadic” rather than “wide-spread,” said MacArthur.

The Centers for Disease Control and the Georgia Department of Public Health agree.

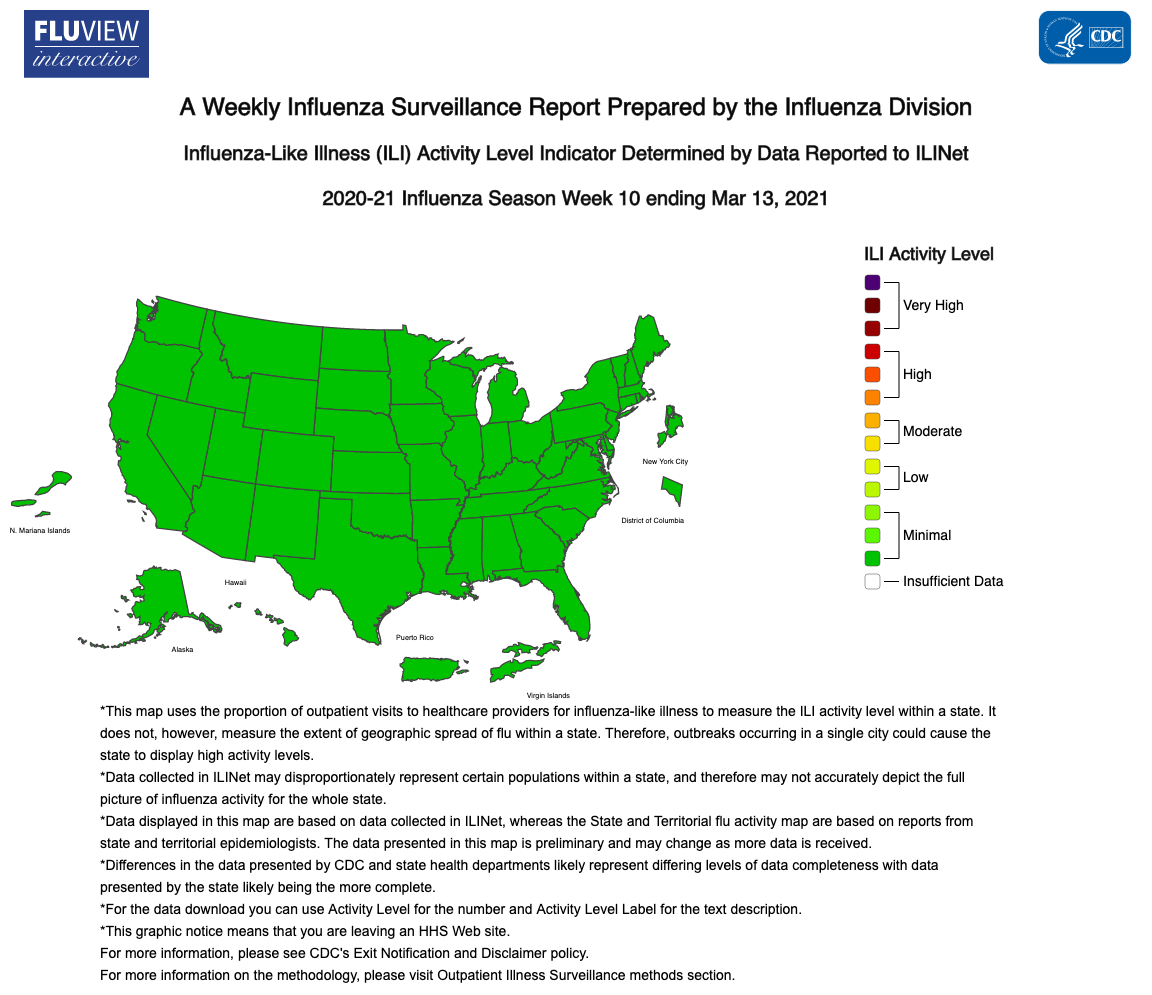

“Seasonal influenza activity in the United States remains lower than usual for this time of year,” according to the CDC website.

The CDC divides the United States into 55 districts for monitoring flu, and as of March 13, the last week for which information is available, all 55 were reporting minimal numbers of flu cases, according to statistics on the health organization’s website.

An “unusually low” number of tests for influenza have come back positive, according to another section of the CDC website. Usually by this part of the flu season, around 3 percent of doctor’s visits are for flu. In the week of March 13, the last week for which statistics are available, fewer than 1 percent of doctor’s visits nationally were for flu.

The most recent data for Georgia indicates there were no flu-related deaths or hospitalizations for the week ending March 12, according to the Georgia Department of Public Health’s weekly influenza report. Only two Georgians have died of flu this year, and both people who died were over 50 years old. Of all the Georgia cases sent for testing, fewer than 1 percent were positive for flu.

Georgia’s two deaths from flu this year can be compared to 71 deaths last year, according to Nancy Nydam of the Georgia Department of Public Health. Hospitalizations in Atlanta, the only city for which records are kept, have peaked at 32 this year compared with 2,238 last year, she added.

The CDC estimates between 9.3 million and 49 million Americans have gotten flu each year since 2010. Final figures for the 2019-2020 flu season are not yet available, but the CDC estimates some 22,000 people died of flu in the United States during that flu season.

American physicians and health officials looked at 2020 data out of the Southern Hemisphere to predict a decline in the number of flu cases, MacArthur said. They looked at data from places like New Zealand and Australia and saw virtually no flu in March of last year. That was when the COVID-19 pandemic was beginning, but even with the onset of winter, the Southern Hemisphere was experiencing an unusually light flu season, he said.

MacArthur even thinks this year’s flu season either may be over or maybe is close to over. In a usual year, flu season extends through the end of March or in early April. Numbers have been so low, however, “Perhaps this year, we’re essentially there,” MacArthur said.

Both Nydham and MacArthur agree that the reason flu is down, ironically, is COVID-19. More specifically, flu is down because the precautions Americans have taken to combat the coronavirus have also worked against the flu.

“It’s the same sort of principle,” MacArthur said. “If you wear a mask, you reduce the amount of virus that will infect you or others. The same with social distancing.”

Another factor in keeping flu numbers down this year was the number of people who got flu shots.

“People really wanted to get vaccinated, maybe more than for a while,” MacArthur said.

The CDC urged manufacturers and distributors to make more doses of flu vaccine available for the 2020/2021 flu season. Early in the season, the CDC anticipated some 194 million to 198 million doses would be available for this year. By the end of February, 193.8 million doses – a record number — had shipped, according to the CDC website.

COVID-19 virus. Photo courtesy of Centers for Disease Control and Prevention

Flu virus. Photo courtesy Centers for Disease Control and Preventoin

COVID-19 and the flu may seem like similar illnesses because both affect the respiratory system, but they’re not all that similar, according to MacArthur. For one thing, the two illnesses are caused by different viruses. MacArthur noted that flu infects the upper respiratory system while the coronavirus infects the lower.

Both COVID-19 and flu are spread primarily by droplets that are expelled when sick people talk, cough or sneeze. When an uninfected person inhales the droplets, or if someone gets the droplets on their hands and touch their mouths, noses or eyes, they can become infected.

Coronavirus has a much wider range of symptoms, however. About half of those who are ill with COVID-19 do not have a fever, but fever is very common with flu. COVID-19 also causes a loss of smell and taste, as well as gastrointestinal issues, and fatigue is much more pronounced, MacArthur said.

A year out from the first cases, and much more is known about the disease and its symptoms, MacArthur said. For example, while fever was thought to be a COVID-19 symptom early on, scientists and physicians know now it is not one of the main symptoms.

Further, while flu is known to go away in warm weather, it doesn’t look like the coronavirus does, according to MacArthur.

“We think flu goes away in the summer because of humidity rather than heat,” MacArthur said. “Flue travels farther in dry conditions. We don’t think covid responds to either heat or humidity.”

He added that in drier parts of the United States such as Arizona, it’s common for people to get flu vaccinations twice a year.

COVID-19 appears to be more contagious and to make people sicker than the flu, according to the CDC. Those who have COVID-19 are also contagious longer.

While coronavirus precautions and vaccines have the potential to end the pandemic, Americans are pitting those measures against not just the original form of COVID-19 but also variants that have emerged, MacArthur said.

He believes the three vaccines available to Americans will be good against the British variant that has emerged. He says they may be less effective against the South African version, though they should be good enough to prevent serious illness.

Mutations of the disease are not the only concern MacArthur has for the future. He says he worries about a variation developing that can jump from humans to animals.

“We know there are non-humans covid can infect,” he said. “We think it came from bats, after all, and we know some big cats like tigers have gotten infected.”

In the West Jutland area of Denmark, 214 people have been infected with COVID-19 by minks, according to the World Health Organization, and another 12 human cases were caused by a variant form of coronavirus from minks. The minks were infected by humans who had COVID-19. Six countries have reported finding COVID-19-infected minks. The six include Denmark, the Netherlands, Spain, Sweden, Italy and the United States.

Denmark has culled all farmed mink in that country – -a total of 17 million, according to the WHO.

“If something like poultry gets infected, it could be bad,” MacArthur said.

In any case, COVID-19 will likely be around for several years yet, MacArthur expects. Given the current vaccination rate, he anticipates it will be three to four years before a majority of the world is vaccinated. Problems with vaccine rollouts have plagued not just developing countries but parts of Europe as well.

“German citizens are upset at the trouble they’re having getting vaccinated,” MacArthur said. “German physicians are upset, too.”

Vaccines are available to Europe, but the European Union has run into bureaucratic and logistical problems, and that means vaccination rates among member states are lagging behind the United States and the United Kingdom, according to MacArthur.

On a more hopeful note, MacArthur predicted that travel, even international travel, would likely be safe, provide the vaccine lasts somewhere around six months.

Debbie Reddin van Tuyll is Editor-in-chief of The Augusta Press. Reach her at debbie@theaugustapress.com