Editors Note: From Behind Closed Doors is a series that delves into the characteristics and consequences of domestic violence. On Aug. 8, Anna Porzio reported on one woman’s experience and how it fit the textbook definition of domestic violence. This week, she digs deeper into the particulars of domestic violence and uses her own experience with an abusive relationship to illustrate those characteristics and consequences discussed by two local experts.

Eight years is a long time to stay in an unhealthy relationship, pretending that nothing is wrong.

Eight years is a long time not to realize exactly what it is about the relationship that makes it unhealthy, but that’s how long I stayed, trapped in what felt like a time loop with no idea why it was so hard to leave.

As I came to learn through LiveSafe Resources, an Atlanta organization “committed to providing safety and healing to those impacted by domestic violence” according to its mission statement, the time loop I found myself trapped in was the cycle of abuse.

MORE: From Behind Closed Doors: Domestic Violence Survivor Tells Her Story

I resisted the idea at first.

I distinctly remembered dancing with him in our kitchen and laughing together about nothing at all. It took me a while to recognize that those times made up only a handful of moments, sprinkled in among countless others when I was made to feel inadequate and dispensable. Those seemingly happy moments were always the calm before the storm.

It is natural for a person to feel stuck in an abusive relationship, trying to get back to what they remember as a happy relationship, according to Dr. Allison Foley. Foley is an associate professor of criminal justice and director of the Women and Gender Studies program at Augusta University.

“An abusive relationship does not start out as an abusive relationship. It starts out as an amazing, wonderful relationship,” she said. “There’s romance, and there’s love and passion, and then it becomes something else.”

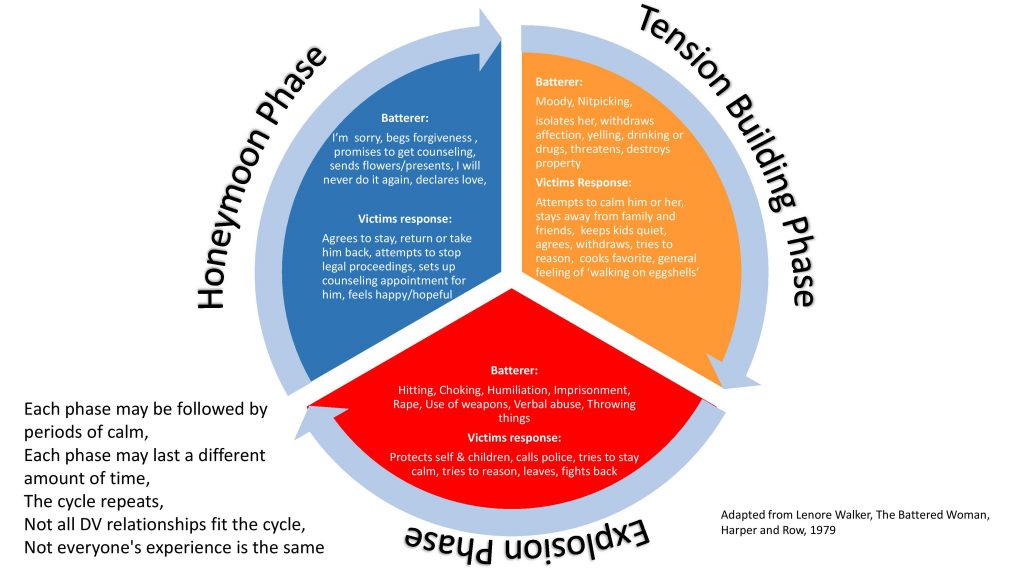

Three distinct phases are the standard for describing the cycle of abuse: the tension building, the explosion and the honeymoon phase, said Foley.

The cycle begins with the tension building phase, which is usually the longest phase, according to Dr. Amy House, an Augusta University clinical psychologist and professor of psychiatry and health behavior.

“The victim may try to control the situation to avoid violence or aggression,” House said. “There might be a sense of ‘walking on eggshells,’ and there may be emotional abuse that occurs during this time.”

The tension building phase may include name calling or intimidation. The abuser may become possessive and try to control where and when their partner can go places, what she can wear, or who he talks to. Abusers may try to isolate their partners from friends and family.

In my case, my ex hated how often I talked to my mother. He once spent an hour lecturing me about how she was going to poison me against him. I started only talking to her when I was in the car running errands. I was so worried about setting off his anger that dodging conflict became a survival tactic.

“We all have conflict in our relationships,” Foley said, “but in an abusive relationship, it escalates to violence.”

The explosion phase is when the violent incident occurs. This phase can consist of an outburst of physical, sexual, verbal or other aggressive behavior, according to House. It takes shape differently in each relationship.

One day, we got into an argument over how long it took me to clean our bathroom and which cleaning products I used. Within minutes, I found myself lying on the floor, pinned underneath him as he gripped both hands around my throat.

Another time, I returned home from the dry cleaner after dropping off his dress shirts. They were going to be ready the following day by 5 p.m. He wanted them by noon. He threw a glass of water in my face and told me I was lucky it was water and not his fist.

Most commonly though, when something set him off, he would take away my credit card and my car keys, trapping me in the house until I submitted to his control.

When the proverbial smoke clears, the honeymoon phase begins. It is during this phase, House said, that the abuser may express remorse or apologize. He or she might make promises to change, offer gifts or shower the victim with affection. The victim convinces themselves that it won’t happen again or that it was not as bad as they thought it was.

A handwritten letter is stashed away in a drawer somewhere in my house that talks about how careless he was with my heart. On a shelf in my family’s basement sits a snow globe engraved with beautiful words thanking me for my strength, all that I had done for him and for always standing by his side.

I convinced myself that his words meant it would all be okay. I must have overreacted. Surely, he had not meant to hurt me.

“The victim of abuse feels hopeful about the relationship again, and things are idealized again,” House said.

House and Foley agree that it is the honeymoon phase that makes it so hard to report the abuse or to leave.

“There’s love there. Most people don’t want terrible things to happen to the person they love. They want the bad thing that person is doing to stop,” Foley said.

However, House said that in most cases, the honeymoon phase tends to disappear over time.

I became accustomed to the stillness between outbursts. I accepted that never again really meant tomorrow, and it was never going to stop until I made it stop. It took me a full year to gather the courage to walk out the door.

MORE: Opinion: Michael Meyers on Seeking Crime Reform in Augusta

Many abusers will threaten their victims or the victims’ families with physical harm or death if they leave, according to House.

“Those are realistic fears,” House said. “The statistics tell us that leaving is the most dangerous time for victims of intimate partner violence, even after they’ve left the relationship.”

When I left my abuser, he threatened suicide, had my house broken into twice, made countless threats and put me in the hospital with a concussion after closing the liftgate of his SUV on my head. For seven months I refused to turn off the flood lights outside my house. There were nights I sat awake, jumping every time an acorn fell off the tree behind my house and hit my back porch.

House said that is why places like Safe Homes of Augusta, or LiveSafe Resources in Atlanta are so vital in the aftermath of leaving an abusive relationship.

Even after the physical danger is gone, survivors of domestic violence are still living with the aftermath of the abuse they faced, House said.

“They may be living with symptoms of post-traumatic stress or experiencing depression or anxiety, and sometimes those are things that require mental health care to recover,” House said.

The hardest part about healing from my abusive relationship was giving myself the permission to grieve. The logical part of me knew that leaving was the only thing to do, but it was still the most intense heartbreak I had ever felt. I felt lost.

It was then that someone offered me the perspective that I believe saved my life.

“The grief you are feeling is very real, but you are not grieving him,” they said. “You are grieving the idea of him, and of the life you built for the two of you in your mind. It is the death of your hope for your future together, and that pain is as real as with any death.”

So, I didn’t go back.

I taught myself to trust again, little by little, reminding myself that not everyone is him. The nightmares still come some nights, but they are fewer and farther between as time goes by, and I don’t need to leave a light on to sleep anymore.

I found my voice and my self-worth, two concepts I had forgotten existed, and I reclaimed my power.

Most importantly, I never went back.

Anna Porzio is a researcher and editorial assistant. Reach her at anna@theaugustapress.com.