In the early 1960’s, the Augusta International Raceway, located in Hephzibah, was a burgeoning hub of racing for the state of Georgia that showed nothing but promise.

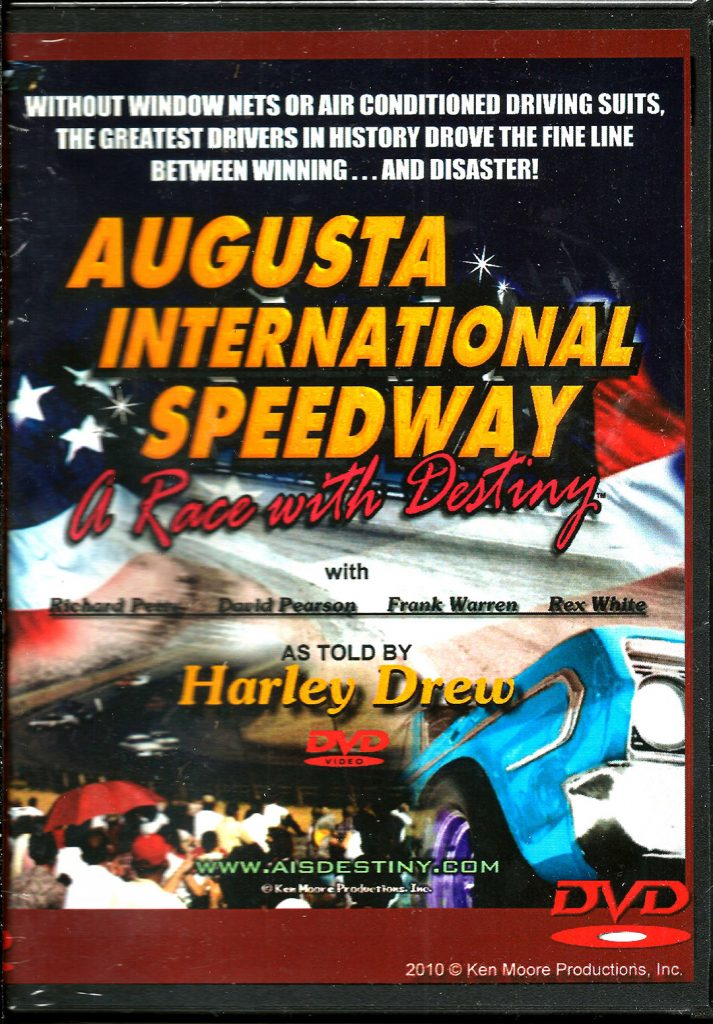

A racing legend founded the racing center and designed its unique 3.2-mile road course. Many racers of the day drove on it from 1960 through 1964. At one point, it was the largest racing facility in the United States. It hosted 13 major racing events, including multiple NASCAR events.

[adrotate banner=”28″]

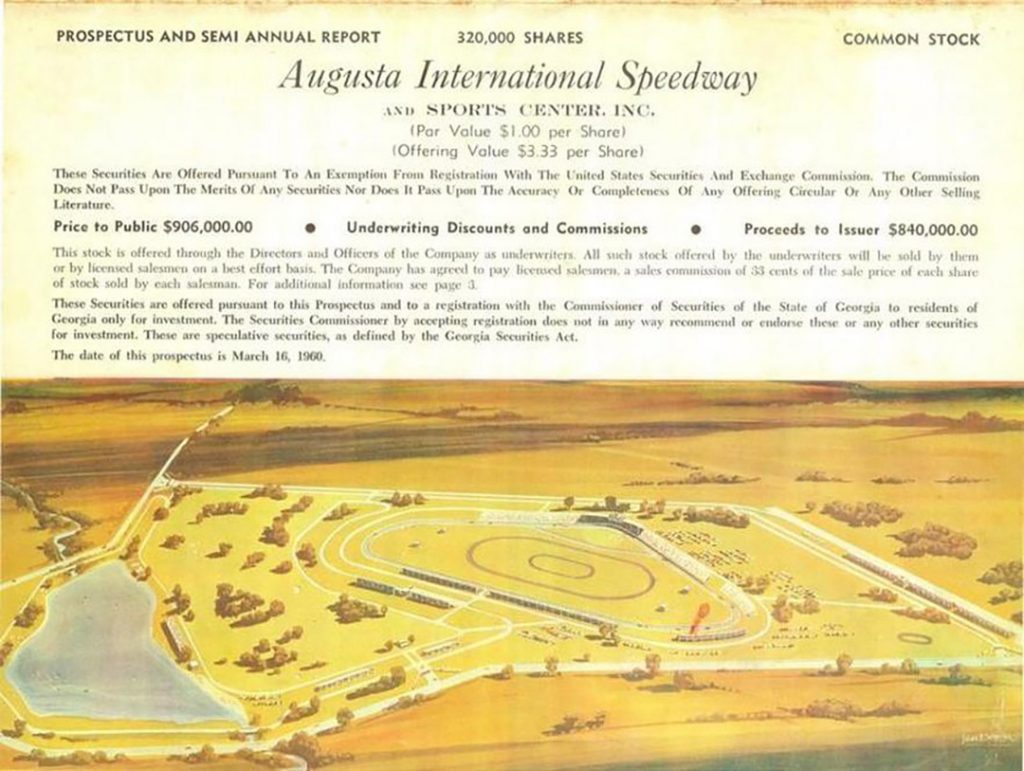

In 1960, Bob Burson, a used car salesman, and his other partners Mike Padgett, the future state representative, and Pierce Farmer, among others, founded the raceway. They founded a half-mile drag strip in Augusta. Then, they added a micro-midget track, a kart track, a motorcycle track, and a half-mile oval. Later, they planned on adding a golf course and a hydro-plane boat course.

Racing legend Glenn “Fireball” Roberts designed the 3.2-mile racetrack that the raceway became famous for. The partners funded the raceway through investors.

As someone who lived through the events, Harvey Tollison can tell the rest of the story.

Racing has been Tollison’s whole life. His father, Frank Tollison, and his mother, Vonetta Tollison, took him to his first race when he was only 1 year old. When they weren’t at racetracks, he was helping his father fix up Plymouths and Dodges with his friend Hawke that they would run on the Augusta Speedway, Augusta International Raceway’s name before it was changed.

“Growing up, I thought everyone had a race car in their house,” Tollison said.

Tollison had gone to the Augusta International Speedway with his parents, but he would not become a part of the racing community until an unlikely series of events in 1964.

[adrotate banner=”19″]

One day in 1964, Tollison had reluctantly joined his mother and his then 10-year-old sister Joy with their Girl Scout troop on a day trip to the forestry unit on Tobacco Road. Being a bored 14-year-old who did not want to spend the day with his mother and a group of little girls, Tollison asked his mother if he could walk to the racetrack nearby. She agreed and allowed him to walk there.

Once Tollison made his way there, he walked to the half-mile. Then, he watched the men work for a while and made a decision that would change his life.

In his words, Tollison made his way to the office and asked the man in charge “if there were any jobs a 14-year-old could do.”

The man Tollison talked to was Hank Schoolfield, the then editor-in-chief of Southern Motor Racing Magazine. Schoolfield was taking care of the promotion for the main track and had just started the magazine the week before. So, for the next race, Tollison sold the magazines. That was his job for the remainder of 1964.

In 1965, B.H. Newman took over as the track’s new promoter, partially because his son Barry wanted to race there. Barry and Tollison were friends. Tollison would help Barry fix his car for the races and answer the phone for his father B.H. Later that year, he went on to write for Southern Motor Racing Magazine.

In 1966, when Mike Padgett took over, Tollison moved up to part-time work for the racetrack. His sister took over the magazine’s sales while his mother answered the phones, and his father sold the back pit

[adrotate banner=”31″]

When he had graduated high school in 1967, Tollison worked for Mike Padgett full-time as the assistant-to-the-promoter seven days a week.

Due to Padgett’s career as a state representative and then a state senator, Tollison had to take on many additional duties in addition to the ones he already had. These duties including putting down the oil drive, driving the pace (the car that leads the race when it begins), overseeing the events, driving the ambulance, ran the scoreboard with his next-door neighbor, and hanging the posters to advertise all over the CSRA.

Tollison helped two buses of military veterans get in for free every race. He also made sure that there were at least 3,000 fans in the stands eating well from the concessions for every event just to make sure the bills were paid.

In addition, Tollison handled all the public relations work himself, and he said he did “everything to make sure the tracks were ready for the races.” He even recruited his friend to help him sweep the tracks in exchange for free entry. Tollison was so busy that he had a secretary of his own.

It was not all hard work though. Tollison did get to have fun. For example, he and his younger sister raced match box cars to entertain the guests.

“I always won, and people didn’t like that,” Tollison said.

These racers came from NASCAR, from all over the nation as well as locally. They had a good time on the track and were remarkably friendly off the track.

“With the competitors on the track, most of the time, they were close knit off the track,” Tollison said. “When they (the racers) got on the track, they banged fenders and ran into each other’s bumpers and everything. When they got off the track and went to the shops, if somebody needed something, everybody helped everybody.”

To illustrate, Tollison told a story of how one day his friend Barry was fixing up his car. It was a 1956 Ford that had been wrecked before it was to be used in a race. Tollison and his friends found another 1956 Ford and decided to fix it up themselves for Barry to use in the race instead.

[adrotate banner=”23″]

Tollison spent the week stripping the Ford of its other parts. Then, the Friday before the race when B.H. Newman’s shop had closed for the weekend, Tollison and his friends brought in the Ford and the wrecked car they were taking parts from to transfer to the other Ford. The Ford didn’t have a transmission, an engine, roll bars, or anything, but Tollison did not need to worry. The other racers and mechanics swooped in to help when they heard of their predicament.

“In a period of 24 hours, we built a new race car,” Tollison said. “It went to the track Saturday night. We had to make some minor adjustments at the track, and it finished second in the Feature and won the Championship…We worked 24 hours and had at least a dozen people at it at all times.”

According to Tollison, this kind of camaraderie was considered normal.

The races remained a popular event for the families to attend over the years, but ultimately, the hard work Tollison and everyone else put in was not enough.

“I did everything I could, but I was a teenager with the responsibility of somebody way older,” Tollison said.

Tollison attributed the fall of the Augusta International Raceway to a number of factors, including the deaths of Bob Burson and “Fireball” Roberts. the Nascar Star of the day who designed the 3.2-mile racetrack and patronized the raceway; the sale that lost part of the racetrack; and his own upcoming service in the military.

Tollison and his sister worked at the racetrack until it shut down in 1970, when he was 20 years old, the same year he got married to his wife Deborah and was drafted.

Tollison was trained as an army pharmacist and served in Fort Louis, Wash., and Anchorage, Alaska. Both locations had racetracks that he drove and worked at part-time.

Once he got out of the army in 1974, Tollison returned to Augusta to care for his ailing mother. When he returned, he and his friends decided to travel around the Southeast to race and preserve racing history while working in construction or as a paramedic.

Henry Jones started the Augusta Raceway Preservation Society in 1990, but Tollison and a few of his friends took over when he retired to Savannah. Tollison doesn’t plan on stopping anytime soon.

“It’s what I’ve done all my life,” Tollison said. “We try to keep history going and fix it so that the people that worked so hard and didn’t make any money, all the drivers and owners and all, won’t be forgotten for their efforts.”

Casey Williams is a correspondent for The Augusta Press. Reach her at producers@theaugustapress.com.

[adrotate banner=”41″]